Director Jonathan Glazer’s speech after winning Best Picture at this year’s Academy Awards punctured the banality of the ceremony. Glazer joined a growing movement of Jewish people rejecting the way Jewishness and the Holocaust are being used to justify the genocide in Gaza.

His message is poignantly connected to a key message of the film—don’t let the horror of genocide become a background to our “normal” lives around the world.

The Zone of Interest portrays the real-life Nazi commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss, and his wife, Hedwig, who built an “idyllic” home and life for their family next to the Auschwitz camp.

In his autobiography, Höss wrote, “Every wish that my wife or children expressed was granted to them. My wife’s garden was a paradise of flowers.” Hoss’ five children played with tortoises, cats and lizards at their villa near the Polish city of Krakow; in the summer, the siblings frolicked in a pool in their yard or swam in a nearby river.

Höss was the Nazi officer in charge of Auschwitz, the concentration and extermination camp where the Nazis killed an estimated 1.1 million people—most of them European Jews. Hoss was directly responsible for these killings, which he oversaw as the camp’s longest-serving commandant.

The film intentionally creates a sense of “big brother”, making you feel present in the house with the concentration camp over the wall. This has a haunting resonance with our world now, and the genocide taking place in Gaza.

It was paramount to get rid of anything that would place their story, and that of the Holocaust, safely in the past, “where it feels like a museum piece,” says Glazer, “and we can say: ‘Oh, it’s just a movie.’”

The film was shot to look as modern as possible, in colour on digital cameras with high-tech lenses. “We wanted to see every pixel,” notes cinematographer Lukasz Zal.

Zone of Interest is a welcome change to the slew of Holocaust films that only explain genocide through the pure evil of individual fascists or depict horror for the sake of entertainment.

The focus on the ordinary elements of the life of the Höss family sends a powerful message—that there is horror and brutality in the day-to-day existence of our system that we must not ignore.

While the brutality of Auschwitz is not directly depicted, there is a constant background noise from the camps, of an eerie bellow, punctuated by screams of horror and pain.

“The axiom of the whole project was ‘make it present,’” said Glazer. “We are looking at the perpetrator square in the eye. We can’t dismiss it as a film. We can’t say, ‘I’m safely watching a film.’”

I could not help but think of the Israeli walls built to control Palestinians, where genocide is happening across the checkpoints and border, and Israelis live “normal” lives despite what their government is inflicting beyond the wall. There are hundreds of checkpoints across the occupied West Bank and Israeli settlers expelling Palestinian people from their homes there as the genocide occurs in Gaza.

The film ends at the present-day Auschwitz Museum to remind us that this was real living horror that occurred.

Resistance

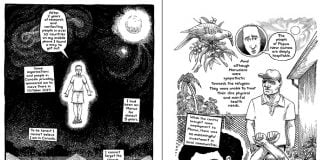

Glazer dedicated his Academy Award to Alexandria Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk, a woman who fought the Nazis as a member of the Polish resistance. He briefly portrays her resistance to the Holocaust and Auschwitz, a story which is rarely portrayed in popular films.

Between 1940 and 1941, the Germans displaced about 17,000 Poles and Jews from Oświęcim (the Polish name for the town of Auschwitz) and nearby villages to build the concentration camp complex. The entire Jewish population of Oświęcim, a total of about 7000, was deported to ghettos. Eight Polish villages were destroyed, and more than a hundred buildings located in the town were demolished.

Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk joined the Polish resistance movement Związek Walki Zbrojnej while still a teenager, alongside thousands of Poles in the area surrounding Auschwitz. If caught, they knew they would be imprisoned and sent to the camps, where death was almost certain.

Nazi guards did not pay as much attention to young Polish girls going in and out of the camps, allowing Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk, who chose the code name “Olena,” and her sister to act as liaisons between the prisoners and the outside world.

Under the guise of working in the mine, they smuggled in food, medicine and warm winter clothes and smuggled out messages. She worked mainly at night, hiding supplies inside the camps where prisoners could find them. The scenes in the film showing her hiding apples in the mud come from her first-person accounts.

Glazer calls Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk the “only light” in the film. The support for the Palestinians from protesters across the border in Egypt to the student encampments in the US demonstrate that this light of resistance is also still present and powerful.

The story of Bystroń-Kołodziejczyk and the growing movement for Palestine is a reminder that even within the darkest of times there is the possibility of resistance and solidarity, across race and borders, against the terrifying normality of genocide enforced by the rulers of our system.

By Feiyi Zhang

The Zone of Interest

Directed by Jonathan Glazer

In cinemas now