Unions formed the Labor Party. But Queensland history shows that again and again, Labor governments have betrayed their own working class supporters, argues James Supple

Queensland produced Australia’s first Labor government in 1899. This was credited as the first Labor government in the world—although it was a minority government, and lasted just a week.

When it won majority government in Queensland in 1915, Labor remained in power with one short interruption until 1957.

The Labor Party was a creation of the trade unions, with the party’s first manifesto announced at a meeting of unionists in 1891 under the Tree of Knowledge at Barcaldine, an open-air meeting spot.

The formation of a political party to represent the working class was a challenge to the existing pro-business parties. It showed workers had begun to recognise they had distinct class interests opposed to those of the employers.

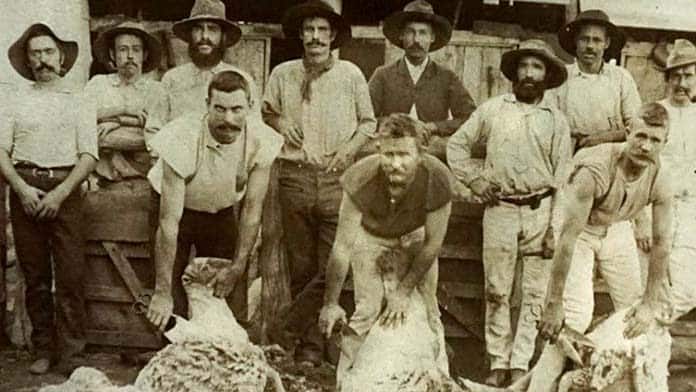

But it was also a response to industrial defeat—the loss of the shearers’ strike, one of a series of major strikes that were crushed in the 1890s.

And the new Labor Party was controlled by the trade union leaders, who are naturally conservative due to their role as professional mediators between workers and bosses, rather than rank-and-file workers themselves. This remains the case today with union leaders controlling half the votes at Labor Party conferences, and often climbing into the ranks of Labor MPs.

Union leaders saw influence in parliament and the use of the state as an alternative to the strikes and industrial action that are the real basis of exerting workers’ power.

But once in government, there were soon tensions between the Labor MPs and the more militant unions. Union officials were elected by the workers in the union, and more directly represented them and relied on them for support.

But, in government, the parliamentary Labor Party and Labor MPs (even if they had previously been union officials) saw their responsibility as running capitalism, not simply representing workers’ interests. That meant that in moments of crisis, they ended up siding with the bosses.

In 1922 the government refused to reverse an Arbitration Court ruling that cut the basic wage.

Union leaders were livid. There were even moves to set up a separate Industrial Labour Party, although this came to nothing.

After failing to influence their political representatives through the Labor Party, in 1925 rail unions used their industrial muscle to stage a one-week strike, forcing the Labor government to end the wage cut for all state government employees.

Shortly afterwards Bill McCormack took over as the new Labor Premier, determined to take a harder line.

Sugar strike

Another major strike broke out on the railways in 1927. This began in what seemed a small local dispute in a mill in South Johnstone, near the sugar town of Innisfail in north Queensland.

Mill work was seasonal, with most workers only employed part of the year. A new management at the mill decided to pay off the whole workforce, reduce staff numbers and re-advertise positions for the new season.

As soon as they re-opened with the new workforce, all the AWU members voted to strike. The union members demanded the mill give preference for jobs to those employed the previous season, as was the practice across the industry. Instead known union activists had been excluded from work.

The workers began picketing but management was intransigent, appealing to local farmers to work the mill as scabs. Although the Arbitration Court ordered the strikers back to work, they refused.

The AWU officials initially did not support the strike, fearing it could spread through the whole sugar industry. The AWU, then as now, was a notoriously right-wing union and a strong supporter of the Labor government.

They tried to take control of the dispute by declaring it an official strike. But the workers rejected their recommendation to accept an arbitration decision. The strikers voted to stay out on strike by a vote of 310 to 28.

Now three months on strike, the strike committee asked the local Innisfail Trades and Labor Council (TLC) to put a ban on the movement of sugar from the mill.

Waterside workers refused to move it, so management tried to ship it by rail.

Railway workers refused in turn, and were stood down.

The Labor Premier Bill McCormack decided to take the unions on—even though the union movement, from more militant unions to the conservative AWU, was united behind the strike. He declared that all members of the Australian Railways Union (ARU) would be summarily dismissed, and only re-hired if they would sign a pledge to obey management instructions—in effect agreeing to scab.

Since it was illegal to single out members of one union, the government sacked all 18,800 railway workers across the state, shutting down the whole rail system.

But trade union solidarity began to crack, with the separate train drivers union the AFULE agreeing to negotiate with McCormack without the ARU. Railway workers also began to break ranks and sign the pledge.

The rail unions gave in, agreeing to sign the pledge in return for no victimisations. The South Johnston mill workers were forced by their union into accepting terms they had previously rejected.

The Premier had set a precedent in how far a Labor government was willing to go to support employers and to break a strike and attack the unions and workers it was supposed to represent.

McCormack arrogantly declared that, “The dispute ended up as it should have ended—in a recognition of the right of parliamentary government.”

The 1948 strike

A Queensland Labor government would resort to even more extreme anti-union measures during the nine week railway strike of 1948.

Following the end of the Second World War there was a surge in strikes, as workers sought to make up for the sacrifices during the war years and the Depression. The strain on the rail system from the war meant the rail system was in need of repair, leading to a series of rail accidents. Workers’ frustrations grew.

Victorian metalworkers on the Federal Award won big pay increases in June 1947.

Government rail workers in Queensland put in a claim at the Arbitration Court for a pay rise to match.

Noting that the pay rises had already been passed on in other states, they asked for a quick decision.

But Queensland had the highest unemployment in the country, and the state government was determined to maintain lower wages in order to attract investors.

The Arbitration Court stalled. It had already been sitting on their claim for the introduction of weekend penalty rates for seven months. Efforts to lobby the Labor government, their employer, to accept the claim failed.

If they waited for arbitration, it was clear they were going to get a bad decision.

Workshop meetings and a secret ballot held in January 1948 voted overwhelmingly for strike action. The unions launched a limited strike restricted to the running sheds where engine repair and maintenance work was done, hoping this would pressure the Labor government into granting them the pay rise.

Instead the government refused to negotiate and adopted ruthless measures to try and break the strike. First it established an emergency system of road transport as an alternative to the rail system.

Then it shut down the railways across Queensland, locking out an additional 14,000 railway workers. This was designed to overwhelm the unions with the cost of supporting so many workers without pay. The federal Labor government aided the betrayal by blocking welfare payments to rail workers.

With the strike now an all-out test of strength against the Labor state government, the Communist Party began to play a crucial role in the dispute. It was near the peak of its influence in the working class, with party members elected as officials in a number of key unions.

Ted Rowe, a Communist Party member and federal official with the Amalgamated Engineering Union, arrived in Queensland to help the Central Disputes Committee, which grouped together unions involved in the strike.

The strikers sought solidarity from other unions, convincing the separate train drivers’ union to strike and attempting to pull out workers on Brisbane’s tramways.

Coal miners voted to black ban coal trains, and railway workers in NSW, Victoria and South Australia also imposed bans.

On 1 March the Seamen’s Union and the Waterside Workers Federation joined the strike, shutting down ports with the aim of disrupting the emergency road transport system.

In response the Labor government secured a return to work order from the Arbitration Court and then declared a “state of emergency”. This allowed it to ban picketing and make advocating strike action a crime. It also backed this up with new draconian enforcement powers that gave the police authority to enter any home or building and disperse gatherings, as well as make arrests without a warrant.

On St Patricks Day, 17 March, hundreds of police used the new powers to attack a union demonstration, intentionally bashing a number of people including lawyer and Communist Party MP, Fred Paterson, who was acting as a legal observer. He was severely injured and took months to recover.

This brutal assault backfired, producing widespread outrage about the extreme attack on civil liberties and a new wave of support for the strikers. Brisbane Trades and Labour Council called a demonstration, but the government refused them a permit. The press spread rumours police were planning another violent assault.

Ten thousand workers defied the law to march to King George Square. The government had failed to break the strike and had to give in.

Skilled railway workers won a large pay rise, almost double what the government had initially offered, including weekend penalty rates. There were no victimisations and unionists imprisoned during the strike were released.

It was a tremendous victory, won through defying the law, solidarity strike action and an actively organised strike campaign, with mass pickets up to 2000 strong outside workplaces.

But it also showed again how far a Labor government would stoop to attack trade unions and hold down wages because it was committed to running the system.

The tensions between the workers, union officials and the Labor Party remains a fundamental characteristic of the Labor Party today.

Many times in the years since 1948, Labor in power has put the interests of capitalism and the employers before those of the workers. The 1948 rail strike is a lesson in the kind of solidarity and union action that will be needed to win pay rises and defend penalty rates—and in why we can’t rely on a Labor government.

This is the first in a series of articles in Solidarity on strikes and Labor governments.