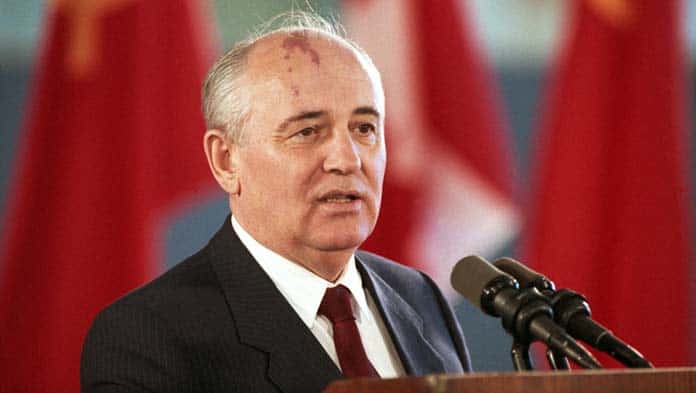

The death of the last Soviet Union leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, was met with a mixed response—and a series of myths. Isabel Ringrose examines the impact of his rule

The death of Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet Union leader, has opened old wounds for some and stirred fond memories for others. From US President Joe Biden to the Dalai Lama, Gorbachev was mourned as a “radical social transformer” who “made the world safer”.

Anthony Albanese labelled the former Communist Party general secretary as “one of the true giants of the 20th century”. Meanwhile Chinese political commentators remembered a man who brought “disaster” by “selling out the interests of his homeland”.

For his supporters and haters, he is the man who split up a socialist state—creating Russia and 14 other independent states in 1991.

Gorbachev’s drive for free market economics left him venerated by Western big business. His shift represented a victory for capitalism in its battle against what was described as Communism in Russia.

On the flip side, the collapse of the Soviet Union and its power in the Eastern Bloc was the nail in the coffin for Stalinism.

This made him loathed by sections of the left, in Russia and beyond. They claimed he abandoned communism for Western capitalism. To hard-line Stalinists, he betrayed the highest form of socialism. But neither account is accurate.

In truth socialism died long before Gorbachev came along.

Revolution

The October revolution of 1917 in Russia was a genuine socialist revolution that saw the working class take power, overthrowing capitalism in a major country for the first and so far only time in history.

But the revolution failed to spread to the more developed areas of Western Europe and was isolated. Although it survived foreign intervention and a terrible civil war, this was at the cost of the destruction of the working class that had made the revolution.

Joseph Stalin led a counter-revolution following the isolation and bureaucratisation of the revolution that saw a shift to state capitalism. The economy was completely state owned, but effectively controlled by a new ruling class of Communist Party bureaucrats.

The new dictatorship exploited workers and peasants as brutally as any other regime, driven by the same desire to accumulate capital and wealth as the free market capitalist ruling classes in the West.

But the eventual collapse of the regime—both at the hands of warring bureaucrats and pressure from below—didn’t improve society or ordinary people’s lives.

As British Marxist Tony Cliff, the founder of the International Socialist Tendency, wrote in 2000, “The years 1989-91 were not a step backward or a step forward for the people at the top, but simply a step sideways.” Russia moved from state capitalist to a capitalist-friendly market system. It was ruled by a capitalist class before and after, but under a different form of capitalism.

Gorbachev was appointed the Soviet Union’s effective leader in 1985, and set out to deal with the contradictions caused by the organisation of the state capitalist economy.

Russia was unable to compete with the West economically and militarily.

A slowdown in production triggered repeated economic crises. Gorbachev’s solution was to clear out the bureaucracy, let privatisation rip and open up to the world market—even at the cost of immense suffering for ordinary people.

In the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc surrounding it, workers had no say. The state was entirely controlled by bureaucrats and driven by competition on the global stage, pouring money into arms as it competed for control of the world with the US.

The pressure of the Cold War arms race burdened the economy. Russia again and again came up against the limits of capital accumulation set by its national economy.

The Soviet economy was organised through the Five Year Plan. Huge industrial projects were sometimes “frozen”.

Investment was suddenly redirected, causing mayhem for production and different branches of the economy. By the 1970s, Soviet state capitalism was suffering from deep stagnation.

Stalinist regimes in Poland, East Germany and Hungary had begun to integrate into world capitalism to overcome the issues of accumulation in their national economies. But loans and trade with the West made them more fragile during global shocks.

Economic crisis

The Soviet Union’s reliance on oil exports meant when prices dropped in the mid-1980s the economy crashed. Between 1981 and 1985 there was “practically no economic growth” as “production of 40 per cent of all industrial goods actually fell”. The crisis caused splits within the bureaucracy between “reformers” and “conservatives”.

The reformers wanted more market measures to improve state capitalism’s efficiency. And the more radical wing wanted a transition to full market capitalism.

The conservatives wanted to consolidate power and protect their system by blocking change, also fearing revolt from below. Gorbachev, a moderate reformer, took power in 1985. His two main pillars of change were perestroika—restructuring—and glasnost, meaning openness.

He pushed for reorganisation in industry and agriculture and criticised corrupt local leaders and managers. Gorbachev became popular in the West for bringing in so-called freedom and justice. Reform to the electoral system meant more than one candidate on some occasions. Secret ballots were introduced in internal party elections and workers could vote for managers.

In reality these measures were a cover to help ram through more market mechanisms. By 1987 just 5 per cent of constituencies had a choice of candidates, and there was no open campaigning over policies. Only 16.7 per cent of people in key positions in local party cells were workers.

When it came to voting for managers, workers could not determine the short list. And successful candidates were approved by all employees—including other managers and supervisors—and signed off by bosses.

Workers’ performance was monitored by factory councils—elected, but under campaigns based on their record of promoting efficiency and productivity. The party organisation was given power to “direct the work of the organisation of collective self-management”.

Gorbachev’s reforms really meant making Russian industry more efficient. In 1984-86, he focused on reform by changing people in top positions. During the first ten months of 1987 he urged for rapid change in speeches and his book Perestroika.

By October, he shifted back to more conciliatory methods after radical reformists were attacked by the Central Committee. Rather than speed-up perestroika and glasnost, he stressed the “dangers” of “going too fast”.

And workers—instead of defending Gorbachev’s reformers or the conservative Stalinists—fought back. In Poland in 1988 workers’ action erupted in the mines, giving the ruling class a taste of the discontent from below.

By July 1989 a huge wave of miners’ strikes swept across Russia. This terrified Gorbachev—who called them “the worst ordeal to befall our country in four years of restructuring”.

Miners later struck again in 1991 to call for his resignation. In Czechoslovakia in 1989 three million workers took part in a two hour general strike while half a million demonstrated in the capital.

In Romania an armed insurrection toppled the dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. The fragility of the bureaucracy’s hold was evident from the shockwaves the strikes caused.

Gorbachev’s attempts at reform were not enough. His inability to solve the crisis caused more splits. After a failed coup in August 1991 by conservative bureaucrats, which crumbled after three days, the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc fell and Gorbachev resigned as president on 25 December 1991.

Social crisis

The market transition and privatisation caused a social crisis and weakened the state. GDP plummeted and ordinary people paid the price through unpaid wages, unemployment and poverty.

Meanwhile the old ruling class managed to maintain its class power, despite the failures of its long-ruling party. They continued to control the economy, society and politics.

Chris Harman, former editor of Socialist Worker, argued in 1990, “The old people at the top raved about betrayal and even on occasions fantasised about telling their police to open fire. But key structures below them were already run by people who, at least privately, accepted the new multinational capitalist common sense.”

Social relations between bosses and workers didn’t change. Communist politicians become “democratic” politicians.

The managers of state-owned companies became managers or owners of newly privatised companies, which saw a layer of oligarchs emerge able to reap billions.

In some countries opposition movements and capitalist newcomers were included in private banking and the media. But the logic of global capitalism was welcomed.

It seemed possible for a time that Russia could work with the West. Rather than be subordinated to its rule, Russia could be part of the same system.

But growing rivalry, economic competition and Nato expansion ended that. The vision failed as the US grabbed more opportunity to expand and dominate militarily.

In the end, Gorbachev was neither the hero that saved Russia nor the betrayer of socialism. Pressure from below and unamendable splits in the bureaucracy triggered by crisis and partial reform led to the death of the Soviet Union.

And the state capitalism born from Stalinism proves Russia’s only experience of true socialism was during the revolutionary years after 1917.

Republished from Socialist Worker UK