The current battle against unelected institutions in Greece isn’t the first. Dave Sewell looks at the July Days in 1965—and how that movement could have won

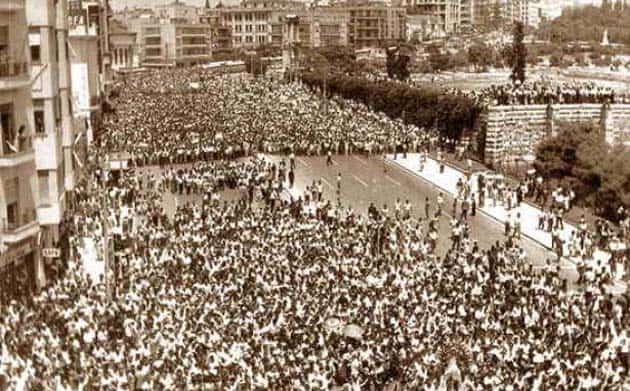

Fifty years ago the streets of Athens shook with mass strikes and protests. A king’s undemocratic attempt to overturn a popular vote provoked the “July Days”.

Poet Fontas Lathis wrote one of the definitive first-hand accounts. He told Solidarity’s sister newspaper in Greece, Workers Solidarity, “The July Days were unique.

“Never before had there been such spontaneous mobilisations. For months people only went to their houses to rest—they had made the streets their home.

“The demonstrations were dominated by optimism and a fighting spirit that made them unpredictable, and escaped the narrow confines planned by the leadership.

“As part of the masses, for the first time everyone felt strong.”

Alkis Rigos, a student activist at the time, told Workers Solidarity, “We are talking about a society whose every molecule was on the boil.”

The “royal coup” came on 15 July 1965. Prime minister Georgios Papandreou wanted to take on the role of defence minister. The king vetoed the cabinet, and told Papandreou to accept it or resign.

He had a successor ready to take over—and bribed “apostates” from Papandreou’s party to back him. But their government lasted barely a month.

Alkis said, “People revolted against the naked intervention of the palace to remove the elected prime minister.

“They came out in the streets in a mass movement for 70 days, and told the king, ‘The people don’t want you, take your mother and off you go’.

“In short, the people in the streets were saying what the political system never dared articulate.”

Papandreou came close to backing down, but the opposition in the streets led him to demand a reversal of the coup.

His Centre Union party had no mass membership. The banned Communist Party (KKE) and its legal front organisation, the United Democratic Left (EDA) did—and they dominated the movement.

The Communist Party retained great prestige as a result of its role in the resistance movement during the Second World War.

They wanted a constitutional monarchy that would allow them to form a government, and opposed demands for the removal of the King. But protesters frequently left them behind.

Fontas remembered, “Each time we marched it was the majority—not just a few hotheads—who wanted to carry on to the palace. The leadership had difficulty holding the crowd back.”

Police arrested hundreds on a demonstration on 21 July. Student Sotiris Petroulas, an EDA youth leader, was killed. The state blamed the teargas—but neck wounds suggested strangulation.

Alkis explained how the state tried to bury his corpse in secret—but protesters blocked the mortuary.

“This thwarted the government’s plans and ensured there would be a proper funeral,” he said. “And the funeral became a mass popular mobilisation.”

The following week workers defied a call by the EDA leadership for them to go home quietly after a general strike.

They pushed past EDA rally marshals and marched through Athens shouting, “Sotiris lives” and called for an end to the monarchy.

It was the first political general strike since 1946. Athens was brought to a complete standstill, with shops closing, the last public transport services and taxis stopping and workers taking over the centre of the city.

One government fell on the 20 August, another on 22 September. Three more would go over the next two years.

No government could satisfy the movement on the streets and the anti-democratic “deep state”.

But the EDA leadership’s electoral focus began to demobilise the protests.

Elections in May 1967 would have likely seen it enter the government. But right wing army officers seized power in a military coup on 21 April.

They arrested everyone from street protesters to right-wing politicians, ushering in seven years of dictatorship.

The movement that could have stopped them had been frittered away.

Historian Michalis Limberatos told Workers Solidarity it was an unnecessary tragedy.

“If instead of paralysing the movement the left had embraced the demand to expel the king, it would probably have won it,” he said.

“This would have paved the way for other victories, and changed everything.

“That possibility frightened the king then—and the colonels two years later. But the inability of the left to take a revolutionary perspective gave them time to organise their coup.”

The KKE had looked to the Soviet Union. But by the 1960s splits between different regimes that called themselves Communist saw new groups form.

The struggles of July—and the later 1973 Polytechnic Uprising that brought down the military regime—brought new lessons. A new left looked to workers’ strength instead of putting faith in state institutions.

Fontas said, “The July Days were a catalyst for the development of left forces which searched for greater radicalism.

“It was the birth of questioning and challenging old ideas.

“But there wasn’t enough time for it to develop. What was needed was a second round.”

Maria Styllou, editor of the Greek Socialist Workers Party’s Socialism From Below magazine believes that second round may be upon us.

But now prime minister Alexis Tsipras’ party Syriza is in place of EDA and the unelected European Central Bank in place of the king. The European institutions today, like the old monarchy, have contempt for the democratic wishes of the Greek people—demonstrated in the recent “no” vote in the referendum—to end the crippling austerity measures.

In a new edition of a book she co-wrote on the movement Maria wrote, “Without a complete strategy of confrontation, governments of the left are not able to implement their promises.

“And in 1965 the revolutionary left was practically non-existent.

“People in the streets who were told to stop by EDA had no alternative political organisations to turn to. Today this is different.

The July events of 1965 in Greece were a prelude to the wave of struggle that was to sweep the entire world a few years later in 1968. As the 1968 generation did in other countries, in Greece the events of 1965 produced the birth of a new revolutionary left.

“The generation that lived through the July Days and the Polytechnic Uprising has left us a valuable tradition”, writes Maria.

“There is a new wave of anti-capitalism with a strategy of overthrowing the system. Its role in the coming period could be decisive.”

Economic change and social turmoil led to political crisis

The Greek ruling class and British army attacked the Communist-led Greek resistance after the Second World War.

The civil war that followed left in place a regime democratic in name only.

At its centre was an army and monarchy that claimed to have refounded the nation by crushing the left. But by the 1960s an economic boom was reshaping society.

Student numbers increased from 11,000 in 1952 to 68,000 in 1965.

Working class people entered universities that had been the preserve of the rich. They demanded funding for education—not the royal family.

By 1962 peasant struggles were taking off. In the region of Iraklion, grape farmers occupied a building and tobacco farmers clashed with police.

Even some bosses were frustrated at widespread poverty as they tried to sell to a home market.

And a construction strike in December 1960 ushered in a new working class movement.

The Greek police couldn’t stop strikers’ demonstrations. Some 115 local unions combined to launch Greece’s equivalent of the ACTU.

One worker said, “It was the first time I had such an experience, the first time I was part of such a carnival. We felt like we were drunk, like we were capable of anything.”

This social turmoil fuelled a political crisis. By 1958 the United Democratic Left, the front organisation of the Communist Party, was the official opposition.

The US military and secret services had backed the Greek regime as a bulwark against Communism. They began to fear it was becoming too brittle to survive an explosion from below.

They encouraged more liberal MPs who formed a new party, Centre Union.

The assassination of left wing MP Gregorios Lambrakis by right wing extremists in 1963 caused a crisis.

Prime minister Konstantinos Karamanlis called an election, lost it, and fled to France.

The US hoped a new two-party system could offer a “safety valve” for people’s anger. But Papandreou took office after winning 52 per cent of the vote, and the demonstrations and strikes increased. And his moderate programme didn’t spare him from royalist plots.

Socialist Worker UK

Translation by Demetrios Hadjidemetriou