The ABC’s seven-part podcast “Conspiracy? War on the Waterfront” tells the story of the infamous 1998 waterfront dispute, in which more than 1400 workers were sacked by anti-union boss of Patrick Stevedores, Chris Corrigan, in a full-frontal assault on the Maritime Union of Australia.

Corrigan, backed to the hilt by John Howard’s Liberal government, hoped to de-unionise the docks and break one of the country’s strongest unions, threatening the future of the entire union movement.

It is a useful recount of the history with rich interviews around this pivotal struggle of the workers’ movement against neoliberal reforms. It is particularly valuable for those not old enough to remember the pictures of dogs and men in balaclavas driving workers off the wharves and locking the gates on 7 April 1998.

Non-union workers including former military personnel were trained to replace the union workforce in a clandestine operation in Dubai—an operation scuttled only by threats of a blockade of the entire port of Dubai by the International Transport Federation.

Another alternative workforce was put together by the National Farmers Federation, allowing Corrigan to sack his workers across the country.

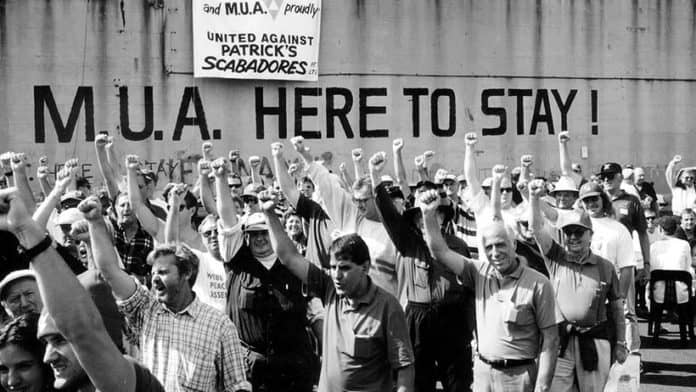

But picket lines at the docks successfully held back the operation of the ports by scab labour—preventing the transport of any goods out of the Patrick docks.

The vibrant pickets were the only thing stopping the employers and the government creating “facts on the ground” of an alternative operation on the wharves.

Police retreat

The memorable morning at East Swanson dock in Melbourne when 1000 police removed their hats and retreated after thousands of workers and community members defended the picket overnight showed the potential of industrial power to beat Corrigan and the government.

It was at nearby Webb dock that Palestine activists stopped work on ships from the Israeli company ZIM last year, with wharfies respecting a community picket line.

The MUA was not defeated on the waterfront—it was here to stay.

But their strategy also relied ultimately on a drawn-out set of legal disputes and appeals in the courts.

The courts’ final ruling inflicted an industrial defeat. Corrigan was ordered to reinstate the union workforce—but not to reverse a sham corporate restructure that had left them employed by companies that were effectively bankrupt.

This meant the union was forced to agree to humiliating conditions including working for nothing and to a series of negotiations with Corrigan. They ended up accepting 600 job cuts as well as a new productivity-based bonus system that divided the workforce.

The result is summarised by then Sydney branch MUA secretary, Jim Donovan: “We lost part of our body but we didn’t lose our soul.”

Howard’s complicity

The podcast focuses on the degree of complicity of John Howard’s Liberal government in the attack, providing new evidence that the Howard government was “like a dog with a bone” determined to break the Maritime Union and its hold over the wharves.

Howard and his Industrial Relations Minister Peter Reith denied any prior knowledge of Corrigan’s plan to sack and replace the workforce. But interviews with Transport Minister John Sharp place himself and Peter Reith in a room in 1997 when a plan was discussed to “train an alternative workforce in Dubai”.

And newly unearthed papers show that John Howard received a letter from his chief of staff explaining that a “major stevedore wants to see you … and needs to know whether he should reactivate the training of Australians offshore to cope with a waterfront dispute”.

This evidence confirms the complicity of the Liberal government in the plot to smash the MUA.

But perhaps the most important conclusions are in the seventh, “bonus” episode, where the implications are drawn out for a union movement that has so far failed to learn the lesson of relying on a two-pronged strategy of legal action in the courts alongside public demonstrations.

There was never any need to accept sackings and concessions to get back in the gate. The MUA leadership deliberately chose to work within the law, refusing to call out P&O workers, employed by the other stevedoring company on the docks, to strike in solidarity. Yet previous national strikes had shown the union’s ability to paralyse shipping and bring the economy to a halt.

The precedent set by the 1998 MUA dispute, that union fights need to stay within legal restrictions on the right to strike, including secondary boycott laws against solidarity action, continues to shackle the Australian union movement.

The CFMEU, one of the few unions willing to defy the law, is facing its most serious attacks in decades, but industrial action has been subordinated to legal action in the High Court.

The union movement needs all its body and soul to take on the new challenges of today, from the cost of living, casualisation, the attacks on the CFMEU, the genocide in Palestine, to the new global threats from Donald Trump’s USA. That means not only remembering but going beyond the politics of the 1998 waterfront dispute.

By Sophie Cotton