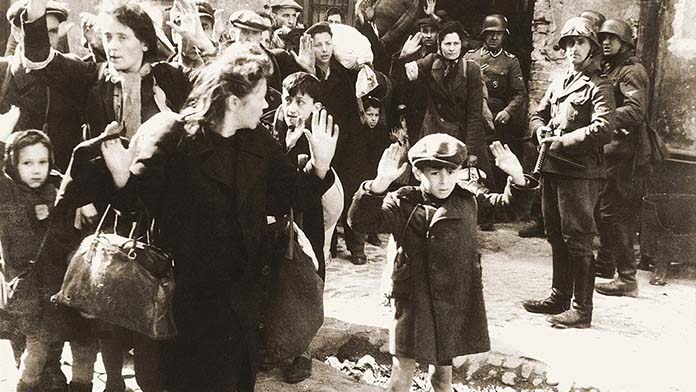

Angus Dermody looks back at how the Jewish population of the Warsaw Ghetto staged a heroic uprising against the Nazi Holocaust—and the leading role of Jewish socialists in it

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising: the high point of Jewish resistance to the Nazi regime.

The uprising lasted almost a month from 19 April 1943 and the heroism of its fighters should be a continued inspiration to opponents of fascism today.

The best account of the uprising is The Ghetto Fights, written in 1945 by Marek Edelman. A member of a Jewish socialist organisation, the General Jewish Labour Bund, Edelman was the last surviving leader of the uprising at the time of his death in 2009. His book provides us with valuable insights into life, politics, and resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The Jewish population of Warsaw was subject to intense persecution when the German occupation of Poland began in 1939. Decrees were put in place restricting the assets and movement of Jewish people and pogroms were launched against them within months.

Jews were forced to move into a single ghetto area within the city, where non-Jewish residents were forced out.

On 15 November 1940, the Warsaw Ghetto was sealed, cutting its Jewish inhabitants off from the outside world. Up to 400,000 Jews were imprisoned in an area of just 3.4 square kilometres.

Conditions in the Ghetto were horrifying, with its residents forced into absolute poverty, starvation and slave labour. Up to 100,000 died of hunger and disease.

The Nazis, however, also relied on the co-operation of the Jewish establishment in the ghetto.

They set up a Jewish Council, or Judenrat, tasked with implementing Nazi directives and imposing control through a Jewish police force.

At the same time, the Bund and other groups continued to organise in secret. Edelman estimates that at one point more than 2000 people were taking part in Bund meetings of five or so individuals.

They continued to organise youth groups, educational initiatives and theatre performances, established co-operatives for those who couldn’t work openly, and printed and distributed illegal newspapers. They also attempted, unsuccessfully at first, to secure weapons.

Deportations

Finally, on 22 July 1942, mass deportations to the extermination camp at Treblinka began. Up to 300,000 Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto would be murdered as part of the Nazi “Final Solution”.

But the Jewish population of the ghetto were told that deportation was simply for “resettlement to the East”.

The Judenrat, following the Nazis’ instructions, notified residents that only a small number of Jews, including those working for German businesses or the Jewish council, could stay. Deportations were carried out by the Jewish police, with a daily quota of 6000, reaching a height of 60,000 within two days.

The Bund and a handful of other groups including socialist Zionists called for resistance. Even then, this was a minority position.

The Judenrat maintained that resistance was unnecessary and that the ghetto’s inhabitants were simply being resettled. Its political dominance, combined with the general feelings of hopelessness that had set in, meant that many believed that resistance was impossible and that working with the Nazis was the only realistic way to save lives.

The first reports of the gas chambers reached the ghetto at the start of 1942 from escapees of the Chelmno extermination camp. Many in the ghetto refused to believe the reports. They could not conceive of such horrors as possible, and the Judenrat dismissed them as exaggerations.

All the Bund could do in this context was warn of the impending Holocaust. By the time deportations stopped on 21 September, the ghetto’s population had been reduced to under 60,000.

The resistance begins

The ZOB, the Jewish Fighting Organisation, was formed as a coalition of left groups including the anti-Zionist socialist Bund and the socialist Zionist Hashomer Hatzair.

In October 1942 they took their first action, after acquiring a handful of pistols through the Bund’s links to the Polish Socialist Party, killing the deputy commander of the Jewish police and the Judenrat’s representative on the deportation committee.

The ZOB’s popularity increased out of these first assaults, which were followed up with an attack on some Jewish foremen who had caused particular suffering to workers in the ghetto. This time, three fighters were arrested—only to be broken out the same night.

In December 1942, they received a shipment of ten pistols from the Polish Underground. This allowed them to plan their first major confrontation with the Nazis.

Before they could carry this out, the Nazis moved on the ghetto for a second round of deportations. This time they faced opposition.

The ZOB joined forces with the ZZW, the Jewish Military Union, linked to right-wing Jewish parties who commanded several hundred fighters in the ghetto.

The fighters engaged the Nazis in a large-scale street battle, costing many of them their lives. They soon changed tactics, favouring partisan resistance from within ghetto apartment buildings.

Armed resistance forced the Nazis to abandon their efforts within days.

One fighting group was captured and taken for deportation. When the order was given to board, not a single one set foot on the train. For this act of resistance, all 60 were executed on the spot. But their example served as a source of inspiration to those still fighting.

The January revolt was costly. Four-fifths of the ZOB’s members died in the fighting.

But it had an enormous effect within the ghetto, with Edelman writing that “now, for the first time, German plans were frustrated. For the first time the halo of omnipotence and invincibility was tom from the Germans’ heads. For the first time the Jew in the street realised that it was possible to do something against the Germans’ will and power.”

Almost the whole population left in the ghetto now vowed to resist the Nazis.

After the fighting concluded, the Polish underground organised the shipment of 50 larger pistols and 55 hand grenades. The partisans were re-organised into four battle groups who were billeted around their posts with guard posts established to warn of any danger.

When the Nazis tried to ship in 12 Jewish foremen to encourage the remaining residents to evacuate, ZOB fighters immediately surrounded their quarters and forced them to flee the ghetto.

When one of them attempted to produce propaganda from the print shop, the resistance confiscated it and made sure it was never distributed.

At the end of January, when the Nazis attempted to register 1000 workers from a cabinetmaker’s shop for deportation, only 25 complied. In March, when they attempted the same at a brushmaker’s shop, not a single one of the 3500 workers registered.

Bakers and merchants began to provide food for resistance fighters, the remaining rich inhabitants of the Ghetto were forced to pay taxes to the ZOB, and the Jewish Council and the Office for Economic Requirements were made to contribute hundreds of thousands of zloty.

Having built their organisation from nothing in October, the ZOB now boasted a revenue of 10 million zloty over three months, which was used to secure more weapons and explosives from the Polish underground.

From January 1943, the resistance was on the offensive for the first time since the occupation of Warsaw in 1939. All the Gestapo in the ghetto were either killed or forced to flee and the resistance effectively took control of the ghetto.

In April 1943 the Nazi regime prepared for the final liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. At 2am on 19 April, Nazi detachments moved in, initially without resistance.

Assuming that the resistance had given up in the face of overwhelming force, the Nazis began establishing a headquarters at a street intersection. Resistance fighters opened fire on them from all sides and by 2pm all had been killed or forced to flee.

This was the first complete victory of the partisans.

For days on end, Nazi soldiers attempted to enter the ghetto, but were continually beaten back.

In the end, realising that the capture of the ghetto was impossible, the Nazis set fire to it, burning it house by house. Thousands were killed in the fires, refusing to give themselves up from hiding places in basements and bunkers.

But the resistance were not defeated. They changed their tactics from open military conflict to defence of the remaining inhabitants, protecting several thousand civilians for weeks on end.

Fighting carried on for weeks, but by May the situation was becoming grave. The resistance was running low on food, water and weapons.

After holding out for over a month, most of the ghetto’s remaining population died either in the fires or in fighting the Nazis.

The few who survived, including Edelman, had to escape beyond the ghetto walls through the sewers, where they continued to resist the Nazi occupation.

The partisans of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising knew that defeat was inevitable. As the uprising began in April, the fighters issued a declaration to the Polish underground that concluded, “All of us will probably perish in the fight, but we shall never surrender!”

Their choice to resist showed the world that, even in the most difficult of circumstances, fascism could be fought.

Their understanding of the class divisions among the Jewish population in the ghetto meant the Bund were able to counter the fatalistic reformism of the Judenrat and organise resistance.

Their actions inspired other Jewish ghettos to rise up in a similar manner, as well as the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, and are still an inspiration today.

As fascism continues to rear its ugly head across the world, we should honour the memory of the Warsaw Ghetto fighters by building the kind of united working class resistance that can ensure the horrors of the Nazi regime are never repeated.