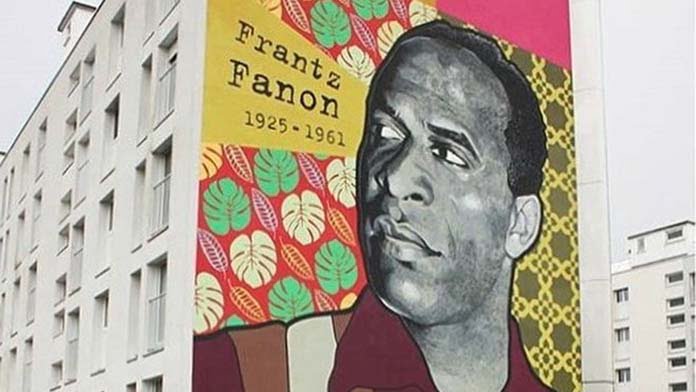

Frantz Fanon’s writings on racism and the difference between colonial violence and violent resistance to it remain valuable today, writes Miro Sandev

Frantz Fanon was an extraordinary anti-colonial and anti-capitalist fighter.

He put his life on the line to fight French colonialism. As Israel’s genocidal war rolls on, Fanon’s uncompromising vision of resistance to racism and colonialism holds key lessons.

Fanon was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique in 1925. The French had colonised it and ran coffee plantations with Black slave labour. Fanon studied medicine in France and later specialised in psychiatry.

As a Black man, his direct experience of racism in France and the hypocrisy of the French liberal ideals shaped his thinking.

Fanon asserted the right of colonised peoples to resist their oppression by any means necessary—the same stance we should apply to Palestinian resistance against Israeli genocide. Brutality is a necessity of colonial domination, therefore anti-colonial violence is an inevitable response.

Fanon argued that we can never equate the violence of the oppressor with the violence of the oppressed—the violence of oppressed peoples is righteous and usually much more limited. He also wrote about the transformative effect that revolutionary violence can have on colonised peoples, helping them see the potential for victory and to overcome deep feelings of inferiority.

Occasionally Fanon did elevate armed resistance to the status of the sole “real struggle” that would “radically mutate” the oppressed. This tendency was influenced by the twists and turns of the anti-colonial struggle in Algeria.

Algerian struggle

French occupation of Algeria led to the genocidal extermination of almost three million Algerians (half of the population) through massacres, disease and poverty.

The National Front for Liberation (FLN) started in 1954 as a small minority in the national movement that was committed to armed resistance against the French. It established a militant agenda, calling for a “social” republic after independence, with serious social and economic reforms.

Fanon moved to Algeria and threw himself into the anti-colonial movement. He helped write and edit the FLN paper and was a spokesperson for the organisation.

A year after he got involved, the Battle of Algiers broke out in 1956. The FLN employed both workers’ strikes and terror attacks against French settlers in the capital, where many Algerians lived.

An eight-day strike paralysed the city in January 1957, but was broken by repression.

The French managed to put down the FLN’s insurgency in Algiers in 1957 and its leaders were hunted down, murdered or forced into exile. But the brutality of the French repression won new support for the rebels. The revolution pulled in and radicalised wider layers of society.

Fanon’s book about the Algerian struggle Studies in a Dying Colonialism has as its theme the Marxist idea that people’s consciousness changes in struggle. Marx wrote that people join movements with a variety of contradictory ideas; it is during collective struggle that people become confident and open to new possibilities.

The years 1956 to 1960 showed all the signs of this. The struggle that had been launched in 1954 by a small group had become a mass movement that pulled in urban and rural areas, men and women, in the armed struggles and city demonstrations, riots and strikes.

Men and women were forced to re-examine their relationships. The post-independence government estimated that 11,000 women had actively participated in the fight for liberation, with about 3 per cent of these fighting in combat.

However, after the Battle of Algiers the FLN strategy shifted to focus solely on military confrontation. The “revolution” became controlled from above. Radical urban trade unionists and students were encouraged to leave their places of work to fight in the countryside. Partly this was driven by the fact that the European settlers were concentrated in the cities.

This shift by the FLN had a profound effect on Fanon’s thinking, and he increasingly looked to the peasants as the agent of revolution. The other influence on him was the failure of the Stalinised French Communist Party (the PCF) to support the anti-colonial struggle in Algeria.

Working class

The PCF did not support independence until 1959, as it was trying to form governing coalitions with right-wing parties in France that strongly opposed independence.

The Communist Party of Algeria was initially not much better. When the FLN began armed attacks, it put out a statement condemning violence “on both sides”, as many on the left today have done in relation to the violence of Israel and Hamas.

Fanon was disappointed and angered that most of the French left had either fudged the question of fighting for Algerian liberation or outright opposed it. This fanned Fanon’s disillusionment with working class politics as a whole.

Fanon became influenced by Maoist interpretations of socialism, which emphasised the central role of the peasantry in revolutionary struggle while holding a deep suspicion towards the working class (the proletariat).

He wrote, “The proletariat is the nucleus of the colonised population which has been most pampered by the colonial regime. The embryonic proletariat of the towns is in a comparatively privileged position.”

Fanon accepted the widespread argument that the organised working class had been effectively “bought off” with the profits of imperialist exploitation, and that revolutionary action against the new African ruling classes would only come from the poorest rural masses and the unemployed and poor in urban areas.

But the actual history of decolonisation in Africa reveals a powerful working class, often leading the struggle for national liberation. Workers were able to paralyse the colonial machine by their position at the heart of the system’s profit-making in factories, mines and docks.

There was a wave of working class militancy after 1945 in Egypt, Syria and Iraq.

In Algeria, the working class demonstrations in the cities and towns across Algeria in December 1960 forced the French to accept that they would have to leave—this was a movement that was not controlled or organised by the FLN.

In 1964 in Nigeria thousands of workers joined a general strike for a pay rise after MPs awarded themselves a big increase. After 12 days of struggle, the parliamentarians gave in. Nigerian workers were to use the tactic repeatedly, with oil and dock workers soon on the front lines of the struggle.

The example of Nigeria was followed by Black workers in apartheid South Africa. Waves of mass strikes there shook the system so greatly that eventually, it was forced to seek peace with its opponents, and apartheid was dismantled.

But there were also important weaknesses. There was an absence of any working class party within these strikes and protests that could provide the leadership of the national liberation movements. What was needed was an urban and worker-led movement can could fuse the national and socialist revolution into a single and ongoing process linked to the countryside.

Limits of national liberation

By 1961 Fanon had been made ambassador of the Algerian provisional government to Ghana, where he met leaders of the national liberation movements from Africa.

He was still giving his all to the FLN, but was critical of some of the decisions the leadership was making and starting to grasp the limitations of national liberation struggles that do not challenge the capitalist system.

In his final book The Wretched of the Earth he highlighted the way upper classes of the colonised people began to manoeuvre to gain advantage after independence and to impose a new system of exploitation—not a colonialist one but still a capitalist one.

He brought a much-needed class analysis to the struggle for power following national liberation. Post-colonial power was caught between a weak national capitalist class and the limitations of global capitalism imposed on any newly developing nation.

In this context it was inevitable that these new Global South capitalists would act to suppress their own people when their demands could not be met within the existing capitalist system.

Fanon detailed much of this suppression. He saw how the Algerian FLN itself was developing in a similar way to other nationalist parties. His book was an attempt to pull back the FLN and prevent the development of this “caste of profiteers”.

Unfortunately, for much of Africa the nationalist revolution hardened into one-party states dedicated to protecting the property of the new ruling class.

This was also true of post-independence Algeria. The FLN banned the Communist Party of Algeria and made itself the only legal party in 1963. Two years later the dictator Houari Boumediene took over in a military coup.

Fanon didn’t live to see an independent Algeria, but he would have been scathing of the FLN’s policies and of Boumediene.

Fanon correctly diagnosed the trap of national liberation within a capitalist global system but he could not provide a solution.

His focus on the peasantry meant he could not advocate for working class tactics like the mass strike and workers councils that are necessary for an anti-colonial revolution to grow over into a socialist one.

But despite these shortcomings, his contribution was enormous. He understood that liberation could not come simply through kicking the colonisers out, but needed a total social revolution.

Fanon wrote that a, “rapid step must be taken from national consciousness towards political and social consciousness”.

The mass protests that ousted the Algerian dictator Abdelaziz Bouteflika in 2019 were a reminder that this social revolution is not yet finished. Recent strikes in the Egyptian textiles factories hark back to the Arab Spring revolts and point to the continued power of the working class as a force for fundamental change.

In a time of revolt in the region and of brutal, imperialist war on Palestine, Fanon’s work is more important than ever to us.