Judy McVey looks at the rise of a new attempt to understand oppression and asks if it can help us fight back today

Marxist ideas about oppression have made a comeback in academia’s social sciences, led by socialist academics in North America and based on Karl Marx’s general theories of capitalism.

In particular, Social Reproduction Theory (SRT) offers an explanation for the way the oppression of women is caused by capitalism, as are other forms of oppression based on “race”, sexuality, ability, age and many others.

The clearly diverse working class is defined broadly by SRT as all those people and their families who must sell their labour power to survive.

Marxist feminist theorists have called for activists to support a fight for socialism that is anti-capitalist and anti-oppression.

New discussions go beyond academic theories which developed from the 1980s, when criticisms emerged, particularly from Black feminists in the US and Australia, that the women’s movement represented the interests of only white middle class women.

This “identity politics” argued that only those who experience a particular oppression can really understand or challenge it. While these ideas could underpin the anti-racist sense of pride in “Black is beautiful” sentiments, they did not allow for working class action to fight oppression collectively. Similarly, privilege theory focused on different inherited personal characteristics as reasons for oppression, thus undermining the potential for solidarity between Black and white, male and female, or gay and straight workers.

Black feminists in the US developed intersectionality theories and argued that workers suffer many inextricably connected oppressions, including class-ism, racism, sexism and homophobia, providing a useful description of how oppressions can combine to shape each person’s actual experience.

While SRT has built on insights from Intersectionality, it argues that class is not merely another form of oppression, rather it is based on exploitation, which in turn shapes and reinforces oppression.

To fight oppression, we must understand the causes of oppression.

Manifesto

This article discusses SRT’s analysis of oppression based on the work of SRT Marxist feminists (who I call “SRTMFs” for this article), particularly the three authors of Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya and Nancy Fraser, but also Susan Ferguson and Aaron Jaffe.[1]

Written in 2018, the Manifesto sought to mobilise feminists to link up with working class campaigns and strikes; they identified a crisis of social reproduction (the social relations and processes involved as working people build their lives and their families) in the context of the austerity driven by neoliberal governments, and new militant struggles in response to the global recession of 2008-09, and the 2016 Chicago (“illegal”) teachers’ strikes.

SRT theorises the way that workers create their lives, families and communities, showing that capitalism distorts and retards their efforts through many forms of oppression in order to reproduce them as compliant wage workers.

The exploitative system requires constant availability of labour; being separated from any means of production and reliant on a wage, workers suffer alienation and oppression.

The pandemic exposed a contradiction—that capitalism relies on labour power to make profits and yet is reluctant to provide the resources necessary for labour to be reproduced. SRTMFs argue this can lead to anti-capitalist resistance.

This article first presents SRT’s analysis of social reproduction and how the theory, based on Marx’s Capital, understands the relationship between exploitation of labour to produce surplus value and the oppression of women within the working class family, which allows for the system to cheaply reproduce labour power. SRTMFs argue Marx and Engels did not provide an analysis of why the working class family persisted and how labour power is created.

Second, I argue that SRT’s explanation for women’s oppression is not convincing because it does not include an historical analysis of the development of the family and the role of the state. In analysing racism, SRT also underplays the role of the capitalist state and ideology in creating racism through the rise of the Atlantic slave trade and using racism to divide the working class. Yet any struggle to remove oppression will need to challenge the state.

SRT and social reproduction

As noted above, for SRTMFs, “social reproduction” refers to those social relations and processes involved as working people build their lives and their families. For capitalism, this situation creates labour power and the capacity to work, while family households have proven to be the most cost-efficient and stable sites for reproducing the regular supply of labour suitably socialised for workplaces.

The nuclear family is where (mostly) women have major responsibility for generational reproduction, giving birth and raising children, which cannot easily be outsourced and automated, but also for care of unemployed, sick and disabled or aged family members. In preparing to go to work the next day, workers replenish themselves within the home, also unpaid.

Workers’ wages to buy essential goods and services, including shelter, food, water and energy, do not cover the household labour to care, cook and clean; this labour is done for love or necessity, not money.

Many aspects of social reproduction are commodified or state-funded, employing mostly casualised workers in childcare, healthcare, aged care, disability support, hospitality (cooks, chefs, waiters), transport and deliveries, warehousing, retail, and food production workers in picking, packing and processing. There are other better paid workers like nurses, teachers and lower-level public servants in the welfare sector.

SRT describes how the system relies on “life-making” to reproduce labour power to make profits, yet it is reluctant to support social reproduction; and suggests this contradiction can lead to a much-needed anti-systemic fightback among SR workers.

Essential workers have taken industrial action and communities built social movement struggles, like that over pollution of the water supply in Flint, Michigan.

SRT argues that oppression is central to these struggles, as well as exploitation. Workers are oppressed as workers, but it’s no coincidence that many also face daily sexism and racism.

So what is women’s oppression, what is racism?

Oppression and SRT

SRTMFs build on an analysis that women’s oppression is caused by capitalism, being based in the processes of reproduction of labour power in the nuclear family, a “unitary theory” which was developed during the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) of the 1960s and ’70s by Lise Vogel and other Marxists. In doing so they rejected “dual systems” theories, often called patriarchy theory, which argued that socialists must fight two systems—patriarchal oppression and capitalist exploitation. Unitary theories argued that capitalism was to blame for women’s oppression.

As a theoretical starting point, most SRTMFs rely on Lise Vogel’s work (Vogel, L. (2013 [1983]), Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Towards a Unitary Theory, Chicago: Haymarket Books). SRTMFs have drawn directly from Marx’s writings, particularly in Capital.[2]

While for SRT, social reproduction refers only to reproducing labour power for the capitalist system, Marx developed the analysis of social reproduction of the capitalist system as a whole to refer to the need to continually reproduce capital and labour, and to continue to produce goods and services, value and profits.

However, Marx omitted to analyse how labour power is created and reproduced, a gap in analysis which Vogel aimed to fill. Bhattacharya argues that to create profits, capitalism requires compliant workers paid as little as possible; oppression is rooted in the processes of poorly resourced social reproduction of that labour power.

If oppression involves not just ideas but also systems to control our bodies and families, and reproduction to keep the system running and profitable, how did it come about?

In focusing on how labour power is created, SRT assumes the role of the family but does not explain the role of the capitalist class and the state in its creation.

Marx, Engels and oppression

Sheila McGregor argues: “Any analysis of social reproduction needs to be embedded in an analysis of capital accumulation and the nature of the capitalist state. It needs to include the way in which the state intervenes in the process of the reproduction of the working class, through legislation surrounding the family, such as laws about marriage, sexual mores and the like and through provision of aspects of social reproduction. These latter are subject to the impact of capitalist crisis and the pressure of class struggle and social movements.”

Engels provided an understanding of the rise of women’s oppression with class society (around 5000 years ago), requiring a state to control the exploited working classes and subordinating women in patriarchal family structures. The family enabled wealthy men to control their wealth and its transmission to the next generation.

Writing in the International Socialism journal, McGregor and Chris Harman base their Marxist analysis on Engels, arguing that the nature of women’s oppression changed with developments under class societies and, in particular, the rise of capitalism.

The violent development of capitalist production in the 19th century separated home from work, but also seemed to shatter the propertyless working class family as women and children were also drawn into waged work. As unsafe industrial situations produced rampant health problems for women and escalating infant mortality, the state reconstructed a working class family.

This was a conscious creation of nuclear family structures, based on privatising the unpaid labour of women, as mothers, to perform social reproduction tasks, imposing new laws, including outlawing abortion, backed by “pro-family” ideology and gender roles on all workers.

Australia was ahead of Britain. MLA Henry Parkes argued in the NSW Legislative Assembly on 14 August 1866: “Our business being to colonise the country, there was only one way to do it—by spreading over it all the associations and connections of family life.”

Significantly, SRTMFs mostly reject Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, following Vogel. However, Jaffe disagrees with Vogel and argues that her analysis tended to wrongly identify women’s ability to give birth as the cause of their oppression. She argued that during childbirth women are forced to rely on their (usually) male partner.

It is not women’s biology that causes oppression: dependence on a partner is a symptom of oppression but not a cause. The capitalist rulers rely on women’s natural abilities to reproduce, consciously promoting the family as the site of privatised childbirth and raising young children, for love.

SRT correctly recognises capitalism is not necessarily reliant on families; there are examples of reproduction undertaken in migrant dormitories and slave camps.

However, there are major advantages in maintaining the nuclear family, which remains low-cost for capitalism and tends to generate more social stability with a more conservative ideology of “family values”; although there are many kinds of families today—not only heterosexual couples but homosexual, single parent, married and unmarried.

Thus, women’s oppression continues, justified for all women ideologically with gender stereotypes, to buttress especially the generational reproduction of labour power cheaply for capital. The burden is heaviest on working class women. The ruling class will fight hard to maintain this system, as they fought to introduce the working class family.

Just as Engels’ work provided a theoretical understanding of how the family came to be a site of oppression, it also points to the potential to transform the processes for the reproduction of labour power, by transforming family structures.

In a socialist society, responsibility for social reproduction can be provided by social and community structures supporting whatever living arrangements members of the new society prefer. Only then can women participate as equals. The Russian revolution of 1917 took some steps to achieve this, after destroying the old state—they set up communal facilities, like state-sponsored laundries, kitchens and childcare, to relieve many women of household tasks.

Such a transformation requires a struggle for socialism which some SRTMFs recognise can be built out of the mass movements developing today. Women workers are part of that struggle.

All workers are affected by women’s oppression; the promotion of heterosexual and binary gendered norms underpins LGBTIQ+ oppression (homosexuality was outlawed initially in many capitalist societies), but other forms of oppression have different causes and different roots in capitalism.

Racism and SRT

SRTMFs argue that SRT can be extended to analyse the experience of oppression of all SR workers. I’ll just look at racism.

Bhattacharya shows that Black people are disadvantaged by the experience of their social reproduction; it is very clear looking at any statistic that people of colour are disadvantaged in allocation of housing, community facilities and healthcare, etc, as well as over-represented in prison populations. She also shows that competition in the labour market contributes to racial disadvantage among the most vulnerable.

However, she does not explain the ruling class power and the role of the state establishing capitalist structures, like immigration regulations and laws that penalise Indigenous peoples and refugees, reinforced by racist ideologies.

Jaffe shows how SRT has broadened Marx’s analysis to drill down into specific ways oppression can shape the way exploitation occurs.

His detailed analysis of intersectionality suggests it is necessary to include the way capital prioritises value and profit, and how social relations emerge historically, to understand why oppression is shaped by and strongly persists within capitalism.

However, his arguments would have been stronger by including Marx and Engels’s discussions about the racism against the Irish workers and the impact of colonialism in binding workers to the ruling class, the importance of slave revolts and the Civil War in the United States. Marx wrote: “Labour cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the black it is branded.”

Racism was constructed in the early days of capitalism to justify the super-exploitation in slavery of Black Africans. The nature of racism has changed but it remains a ruling class tool to divide the working class.

SRT does not include an analysis of the historical role of the capitalist state in imposing racism as well as shaping SR structures including the family.

In the current context the BLM protests exposed the role of the state in dominating Black lives and pointed to the demands for defunding the police, which had immediate practical benefit for the movement and pointed to the future of removing the oppressive state.

A Marxist analysis argues that the capitalist state must be destroyed and replaced by democratic social structures like workers councils. Oppression is not innate to human society and liberation is possible in the process of defeating class society structures.

Oppression and struggle

SR workers share a common experience, as shown in the COVID-19 crisis, of capitalism’s dependence on labour power and this has fed radical actions.

The pandemic has exposed the profit-orientation of capital. On the dangerous COVID frontlines, “essential” workers provide the main survival needs of communities. Yet, we have seen an increase in authoritarian measures to discipline workers, instead of bosses and governments providing proper safety measures, from PPE, to on-site testing and better paid leave.

Dominated by growing inequalities and decline in many families’ income, nuclear families remain contradictory structures, a “haven in a heartless world” to paraphrase Marx, but they can be sites of domestic violence. Unfortunately, carceral strategies are preferred by some feminists and others rather than improved welfare and community services.

This year paramedics, nurses and teachers used strikes and stoppages to force the NSW Liberal government to back down on their proposed public sector pay freeze, some defying Industrial Relations Commission orders to stage industrial action. Nurses took part in rolling walkouts across the state.

SRTMFs argue that capitalist dependence on their labour gives strategic importance to their struggles. They propose that social movement struggles based on social reproduction issues, which are often campaigns against oppression outside the workplace, can unite workers in struggles that are as powerful as those at the point of production. However, it is important to avoid blurring the difference between strikes which can stop profits and other mass actions.

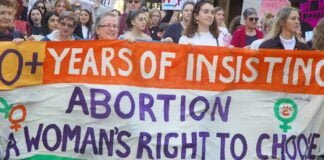

Women at home cannot directly stop profits but have often played militant roles strengthening the action of those on strike. The women’s auxiliaries who built struggles and supported miners’ strikes have a proud history. Community and industrial struggles can unite women based at home and waged workers, a potential shown in the Women’s Strikes, which spread around the globe to fight against capitalist misogyny and anti-woman violence.

Resistance to oppression clearly sharpens the struggle against exploitation and can overcome divisions as workers recognise common interests against capital. Marxists support all these and attempt to build solidarity.

Conclusion

SRT has put a spotlight on the need for a working class-led fight against oppression.

The effects of oppression on working class consciousness are not automatically unifying nor radical, but there can be very radical mass struggles, as we have seen against sexism and racism recently, with BLM struggles clearly winning support among non-Black groups of workers and women’s strikes being supported by men.

Recent struggles have put new forms of solidarity on the agenda with workers often at the centre.

The Marxist strategy to abolish the capitalist state and reshape the family are critical to women’s liberation and socialism, as well as ending racism; it should also inform our strategy today.

The challenge is to connect the struggles that are building against the growing ecological, economic, COVID-19 and social crises, which are all affecting the life chances of the working class, to build a united movement of the 99 per cent, focused on transforming the capitalist system and abolishing exploitation and oppression.

Many thanks to Sheila McGregor and Tom Fiebig for their helpful comments on drafts.

[1] Bhattacharya edited and provides key ideas in Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentering Oppression, in 2017. Susan Ferguson’s 2020 work, Women and Work: Feminism, Labour, and Social Reproduction, provides a history of the development of SR theories. Aaron Jaffe published Social Reproduction Theory and the Socialist Horizon: Work, Power and Political Strategy, in 2020, which extends Marx’s concepts of labour power and oppression, updating and discussing other SRTMFs’ analyses. He argues that SRT is a framework that can enable us to better understand the world “with particular attention paid to the way our embodied labour powers are made and sustained”.

[2] However, SRT tends to reject or ignore the rich tradition of Marxist analysis of women’s oppression and radical practice begun by both Marx and Engels and continued from the late 1800s by revolutionary socialists Eleanor Marx, Clara Zetkin, Alexandra Kollontai and Nadezhda Krupskaya.