Eliot Hoving looks at how Marx developed his ideas out of involvement in the movement for democratic rights in Germany

All the time we are told that history is driven by the ideas and actions of great individuals. Too often this gives the impression that great historical thinkers were simply geniuses that pulled ideas out of their heads. But ideas do not fall from the sky, they reflect the social and material circumstances of their time.

Marx was a genius. But crucially he also lived in the period where capitalist industrial development was just emerging in much of Europe, and took part in the political struggles and revolutions this generated.

This was a time of intellectual ferment as new thinkers attempted to understand these changes in society—and which also produced the rise of the first working class movements against poverty and capitalist crisis.

Karl Marx was born in a quiet town in the German Rhineland in 1818. In his youth Marx showed no indication of his later revolutionary ideas. When Marx attended the University of Bonn in 1835, forced to study law by his parents, his drinking habits led to brawls, and failing grades. Disturbed by this his father forced him to enrol at the University of Berlin, a more strict academic institution.

Marx studied German philosophy and history. He became a member of the radical Young Hegelian grouping, which drew inspiration from the most influential philosopher of the time in Germany, Hegel. Hegel was deeply influenced by the French revolution of 1789, and the enlightenment. He saw history as a dynamic process where opposing forces come into conflict in the fight for a higher level of freedom and consciousness. Hegel’s philosophy was idealist, because he saw the development of ideas as the driving force of history.

Hegel’s final conclusions were reactionary. In The Philosophy of Right Hegel defended the Prussian State, an autocratic German monarchy, as a rational force for reconciling the contradictions and conflicts in society.

In contrast the Young Hegelians, inspired by the French revolution, championed an extension of democratic rights in Prussia. Being at the most radical end of the German bourgeois movement they faced the wrath of Prussian State censorship. Young Hegelians such as Bruno Bauer were banned from academic roles. The Prussian state was clearly not a force for democratic freedoms but a barrier.

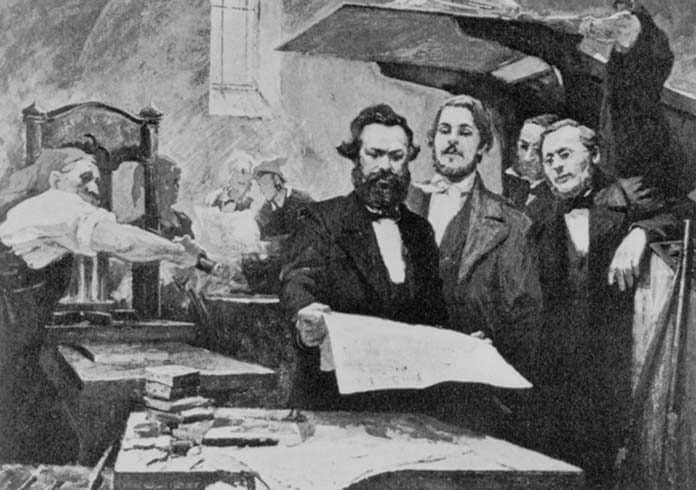

The attacks on the Young Hegelians by the Prussian State thwarted Marx’s hopes to become an academic and he turned to journalism to make a living. In 1842 he started writing for the German newspaper Rheinische Zeitung (RZ), which was funded by industrialists in the German Rhineland.

Nature of the state

Journalism forced on Marx the need to study and write about economic and social issues. For someone schooled in abstract Hegelian philosophy this was a reluctant change. Marx exclaimed: “I experienced for the first time the embarrassment of having to take part in discussions on so-called material interest”. The paper’s owners appointed Marx as its editor, in the hope of exerting pressure on the monarchy for reforms.

Marx still hoped that freedom of the press and open debate would be enough to push Prussia into becoming a democratic state. But the combination of writing on economic conflicts and his encounters with state censorship led Marx to increasingly radical conclusions.

Within the RZ we can find the seeds of Marx’s later theories. For instance Marx opposed laws introduced by the local parliament allowing forested landowners to stop the gathering of dead wood on their property. This had been a traditional right of local peasants. The local government granted landowners the power to issue a fine on the spot upon capturing a wood thief.

Marx challenged the sanctity of modern private property, arguing that the customary rights of the peasants to use the land preceded the landowners’ claim. The government’s adoption of the laws revealed its role as a tool for certain classes to maintain and extend their power rather than a tool for reconciling class interests.

The RZ was eventually censored completely. Marx was forced to resign in March 1843 and the journal was shut down two weeks later. Fleeing in 1843 to France, Marx developed his philosophical ideas to clarify what he had learnt.

In the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Marx attacked Hegel’s idea that the state existed above classes. Hegel’s approach was upside down. He had confused the Prussian state with an ideal state, which only ever existed in his own philosophical musings.

Marx concluded that the state did not represent the universal interests of all but the interests of the landowning and capitalist classes. The state needed to be drastically reformed, which could only take place through revolutionary struggle. Marx championed universal suffrage as a means towards bringing society under greater democratic control.

Working class

How to achieve such a democratic revolution in Germany thus far remained an open question for Marx. However on moving to Paris, Marx found a city bustling with workers clubs, associations, movements and political organisations. At the time over 100,000 German workers worked in Paris alone.

Marx began to identify with the working class, drawn by their culture of solidarity and debate despite their wretched conditions. He remarked, “it is among these ‘barbarians’ of our civilized society that history is making ready the practical elements for the emancipation of man”.

Marx’s early focus on the working class remained tinged by his philosophical upbringing. Marx still saw the working class as the practical tool for revolutionary change. The conscious leadership for such a revolution would still lie with the philosopher whose revolutionary theories would “seize the masses”.

Marx’s turn towards the working class was not entirely unique. France during this period was already home to a variety of socialists and communists. Marx and Engels later set out to transform one such organisation, the League of the Just, into the Communist League.

French socialism was a product of the French revolution, which proclaimed liberty, equality and fraternity on the one hand, but delivered political freedoms only for the property owners, and poverty, mass starvation and inequality for most.

However most socialists before Marx were utopians, they simply imagined new societies free of exploitation and poverty, without a realistic political strategy to bring them about. For example Auguste Blanqui followed the view of Babeuf, executed during the French Revolution in 1797 for inciting a small group to attempt the armed overthrow of the state. Followers of Robert Owen denounced revolution as inevitably ending in disaster and aimed for a peaceful transformation through converting the rich to socialism.

As Engels explained for most of them the working class was “simply the wretched, an example of the need for revolution but not a force to bring it about”.

Capitalism

Marx’s first innovation was to “not dogmatically anticipate the world but rather want to find the new world only through criticism of the old”. His analysis of the potential for a new socialist society was based on an empirical and historical study of capitalism and its real conflicts.

To understand the potential for revolution Marx was drawn to political economy. This was further encouraged when Marx came into contact with Frederick Engels. Engels in his article “Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy” drew socialist conclusions from the theories of British political economy. So began a life long friendship between the two. Marx, inspired by Engels’ work, began to rigorously study capitalism, and the works of Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

Both Smith and Ricardo viewed capitalist society as a distinct social formation, characterised by three main classes: the capitalist class, the landowner class, and the working class. Smith and Ricardo identified the class divisions inside capitalism, but they did not make much of them because they viewed capitalism as natural.

In contrast Marx argued that these class divisions are the cause of instability and social crisis. They pointed towards the potential for the revolutionary transformation of society through working class struggle and the historical transience of capitalism.

Furthermore his collaboration with Engels revealed to Marx the extent to which the working class could self-organise. Engels experienced firsthand in Manchester the destructive process of industrialisation, captured in his study The Condition of the Working Class in England. At the time Britain was the country where both capitalism and working class resistance were most developed.

Peasants dispossessed of their land, and forced into factories for meagre wages, had begun to organise together. The Luddite riots in 1811 and 1812, the birth of the Trade Union movement, and its defeat of the government’s attempt to outlaw unions in 1824, and the Chartists’ struggle for universal suffrage from 1837-1848, displayed the class conflict at the heart of capitalist society.

Workers began to challenge the logic of capitalism itself. In 1833 a Yorkshire building worker wrote, “the trade unions will not only strike for less work and more wages, but they will ultimately abolish wages, become their own masters, and work for each other.” Germany too was rocked by a Silesian workers revolt in 1844.

As Marx would summarise in the Communist Manifesto (1848) the emancipation of the working class would be the act of the working class itself. Only the working class is capable of leading a revolution against capitalism because it alone has the power to halt production, through strike action, and to take over production so that it can be democratically run.

Marxism, as Lenin would later put it, is the “theory and practice of proletarian revolution”. Capitalism’s own crises and its basis in exploitation force workers into struggle. But the development of the organisation and political understanding among the working class necessary for them to lead a revolution is not guaranteed.

Marxists must intervene in the class struggle, to clarify real debates and to improve the chances of revolutionary success. Marx remained a life-long active revolutionary. His committed engagement with the movements of his time through direct participation and theoretical critique are an important legacy for us today.