The coup in Chile showed how far the ruling class will go to maintain their rule, and why only workers’ power can challenge them, argues Ken Olende

Chile’s experiment with socialism brought through parliament came to an abrupt halt 40 years ago this week on 11 September 1973. The military killed some 30,000 people as it overthrew Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity (UP) government.

This earlier 9/11 was a defining event for the left in the 1970s. In the immediate aftermath right wingers around the world said the coup was inevitable because the left wing government had ruined Chile’s economy. On the left a polarisation emerged between those who said that UP had gone too far and those who said that it needed to go further. There is an echo of this argument today, among those who say the violent attacks on the Arab Spring prove that people in the Middle East can’t cope with democracy.

Allende was elected in September 1970, with a 36 percent vote. UP, promising radical left wing reforms, got in because the right was split. The economy was stagnating, real wages were falling and none of the other main parties had anything new to offer.

Chile’s population was then ten million, with almost three million living around the capital, Santiago. The UP coalition included the Communist Party (CP) and the Socialist Party. Allende was a reformist who believed in Keynesian economics. He was determined to change society while playing entirely by the rules of its leaders.

In one of his first acts he guaranteed not to interfere with the church, the education system, the media or the armed forces. Mario Nain, a socialist in Chile at the time, recalled, Allende “was an extremely honest politician. He genuinely believed that society could be reformed by parliamentary means.” Allende’s first reforms were wage rises, land reform and partial nationalisation of the economy. This included the copper mines that generated most of Chile’s foreign earnings. Monica Lucero remembers the excitement of that period, “It started from the most basic things—cleaning up poor neighbourhoods, repairing roads. “Local people organised collectively.”

Allende’s politics were far too radical for either the Chilean ruling class or US leaders. US national security adviser Henry Kissinger notoriously said, “I don’t see why we have to let a country go Marxist just because its people are irresponsible.” Documents released many years later show the CIA cabled its Santiago station saying, “It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup.”

But the coup in Chile was not mainly about the US. The country has its own ruling class, determined to defend its own interests.

UP’s moderate reforms gave enormous hope to the country’s poor. Peasants seized land in the big estates. In the towns poor people took land to build homes on. This was what really scared the rich. Radomiro Tomic, the Christian Democrat Allende had beaten in 1970, complained, “Illegal occupations are not only the work of the ultra-left; they are also the spontaneous action of groups of peasants, workers and miners.” And this mobilisation was popular. Local elections in mid-1971 showed the UP vote increased 14 percent. This was the height of their popularity.

From then on right-wing disruption led to economic problems. The government attacked the workers who had done most to implement its promises and defend what it said it had set out to achieve.

By late 1971 the right were on the offensive in an attempt to disrupt the popularity of the government. Middle class housewives demonstrated on the street against shortages by waving empty saucepans, which many got their maids to carry.

UP responded by trying to demobilise the movement of the poor to reassure the rich. In May 1972 the CP mayor of the industrial city of Concepcion banned a right wing demo and a left-wing counter demo. But he used riot police against the left, killing one demonstrator.

Workers’ power

Workers formed “cordones”, groups bringing together representatives of different workplaces, to organise against the bosses’ strikes and keep production going.

In October 1972 a transport bosses’ strike tried to shut down the economy. It blocked public transport and the delivery of goods. But workers broke the strike by taking control of distribution themselves. Workers fought to keep shops open. All 113 Bata shoe shops in the country got organised. One worker explained, “We’ve formed self defence committees to repel attacks. We’ve already had to face a number, particularly in upper and middle class neighbourhoods.”

A worker at the Ready-Mix concrete plant said, “We’ve got to thank the fascists for showing us that you can’t make a revolution by playing marbles.” Allende responded to show he was running a reliable capitalist government, appointing serving military officers to the cabinet. UP mobilised against workers’ self-organisation—precisely what could protect it from a coup.

Copper miners struck when they were paid less than they were promised at a time of rampant inflation. These miners had been at the heart of fights for civil rights in Chile. Yet the government claimed they were responsible for less well organised workers not getting their due. The argument was as divisive then as now, but the organisations of the left went along with it. A coup in June 1973 failed but crackdowns on workers continued. Yet the general secretary of the CP said on 8 July, “We continue to support absolutely the professional character of the armed institutions. Their enemies are not among the ranks of the people but in the reactionary camp.”

Tuesday 11 September 1973 dawned with air force jets bombing the presidential palace. Mario Nain recalled, “It was total war—a conventional, well equipped, sophisticated army against a completely disarmed population.”

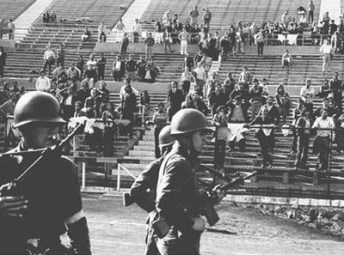

Allende was killed in the attack. The military took over the country’s main football stadium to house 12,000 leftists they had rounded up. During the terror that followed, the military killed up to 30,000 people. Many more were tortured or driven into exile.

General Pinochet led the coup and held power for 17 years, openly championed by the likes of Margaret Thatcher. The hopes of workers and peasants were drowned in blood for a generation, but despite the brutality of Pinochet the movement has revived. The political lessons of how to challenge a powerful, armed state are still very much in the balance, in Egypt as much as South America.

Socialist Worker UK