Kent Ireland examines the union campaign to defend Medibank from Liberal PM Malcolm Fraser, and how it led to a national general strike

The only national general strike in Australia’s history took place in 1976 in response to the Fraser government’s dismantling of Medibank. Around 1.6 million workers struck, bringing the major cities’ public transport networks to a halt and disrupting other services.

Medibank was one of the Whitlam Labor government’s most popular reforms and its successor, Medicare, passed by the Hawke Labor government in 1984, remains popular today. Considering the Coalition’s current attack on Medicare, the 1976 general strike is worth examining for lessons about fighting to defend Medicare today.

Whitlam and Medibank

Gough Whitlam was elected on a platform of expanding social programs such as Medibank, free university education and social security.

Medibank was established as a universal insurance scheme to fund healthcare costs for the whole population. It agreed to meet a standard rate for GP visits and procedures but allowed doctors to continue to run private clinics.

Doctors could “bulk-bill” by accepting the fee set by Medibank. If they wanted to charge more than this amount, they needed to charge the patient their full fee upfront and leave it to them to claim back the rebate. This encouraged doctors to provide services free of charge to the public by eliminating administrative costs. The reconstructed Medicare works in the same way.

Sections of the establishment had initially backed Whitlam, who was from the right-wing of the Labor Party. The Australian captured his relationship to big business when it described how, “Gough Whitlam strode into the grand ballroom of one of Australia’s finest hotels today, and greeted members of the Company Directors’ Association of Australia like brothers.”

But when a major economic crisis began in 1973, Labor quickly fell out of favour with the ruling class.

Whitlam’s Medibank legislation was blocked by the Conservative-controlled Senate until the double dissolution election in 1974. When parliament re-convened after a Labor victory, a joint sitting of both houses passed it into law.

Labor had worked hard to explain the benefits Medibank would have for the healthcare system. They pointed out the excesses of the private health insurers (one had recently purchased a plane for its CEO) as well as the number of people without healthcare who would be covered under the new scheme.

The medical profession and the Liberal Party opposed the idea of universal health care from the outset. Once Medibank began in July 1975, some doctors continued to boycott the system.

The conservatives blocked supply and convinced the Governor-General to dismiss Whitlam as PM in November 1975.

The Liberals under Malcolm Fraser won the election that followed. Their first budget was full of cutbacks and attacks. One of the most discussed was on Medibank. Fraser had decided to introduce a 2.5 per cent levy on incomes to fund the system.

However people would be able to opt out by buying private health insurance. This would have severely undermined Medibank by allowing wealthier people to opt out, undermining the funding necessary to maintain it.

According to socialist historian Tom O’Lincoln, “The government itself expected about half of all taxpayers to opt out. The basic principle of the Medibank scheme—universal health cover—was being undermined as an initial step towards its complete abolition.”

The Liberals hoped to eventually shrink Medibank down to a safety net only for pensioners and the very poor, and force everyone else into private healthcare. This aim has been consistent through the Howard government’s time in power and now through Abbott’s co-payment plan.

In the meantime, however, the system was largely a success. Even the Financial Review praised Medibank as both extending access to healthcare and containing costs. Fraser had chosen to attack one of the more dearly loved aspects of Whitlam’s legacy.

All this meant that, as 1976 started, many unionists were expecting a year of strikes. The union movement had been through a period of intense militancy since the late 1960s. Membership of trade unions reached 56 per cent of the workforce in the mid-1970s. The renewed union militancy was symbolised by the strike to defend Clarrie O’Shea in 1969.

O’Shea, the secretary of the Victorian Tramways Union, was jailed for defying the “Penal Powers”, laws that imposed large fines on unions for taking strike action. There were immediate walkouts and a 24-hour strike by 40 Victorian unions, followed by state-wide strikes in WA, Queensland and SA.

This confidence to openly defy the law helped to fuel further action around wages and conditions. There were three million strike days in 1971, up from one million in 1968, and six million by 1974. Some unions even took strike action over wider social issues, for example the Green bans initiated by the Builders Labourers Federation to halt the redevelopment of The Rocks in Sydney and maintain heritage and working class housing in the area.

After 1974, however, recession weakened workers’ confidence. Fraser’s election managed to breathe some life back into the union movement.

The government had, in early 1976, announced that it would ask the Arbitration Commission, which set workers’ wages, to halve the annual wage increase.

This started the year off with a wave of strikes, including by tug-boat drivers, immobilising 110 ships and costing $1 million a day, and 2500 transport workers at the airport.

Striking for healthcare

In response to the attack on Medibank, pressure began to build on the ACTU to call large scale action. Left-wing unions in Victoria declared that “rank-and-file support was greater than in the 1969 battle for the repeal of the penal provisions”.

But senior union officials and then ACTU leader Bob Hawke did everything they could to derail the campaign. Whitlam had funded Medibank from general revenue, without any specific tax increase to pay for it. Fraser wanted to increase income tax to maintain his slimmed down version through a specific levy. The ACTU offered him an unjustified compromise by announcing that a new levy was acceptable—as long as the scheme itself was not changed.

Workers on the South Coast of NSW led the first major demonstration to defend Medibank on 7 June, with a mass strike of local unionists that gathered 40,000 people to rally through Wollongong. But their attempts to win NSW-wide action through the Labor Council in Sydney were frustrated.

In historically militant Victoria union leaders at Trades Hall proposed just a single four hour strike to a delegates meeting on 9 June. This was proposed jointly by union officials Ken Stone, representing the ring-wing unions, and John Halfpenny representing the left-wing unions.

But rank-and-file workers at the meeting rejected this token stoppage and passed a motion demanding a 24-hour strike instead. The officials at Trades Hall ignored this and proceeded to organise only a four hour strike.

This decision outraged union members. Belatedly the left-wing union officials backed the push for a 24-hour strike to avoid being outflanked by the anger.

A meeting attended by 6000 unionists on the day of the four hour strike on 16 June passed another resolution for a 24-hour strike. This time left-wing official John Halfpenny spoke in favour of the motion.

As more union leaders realised that they could not sit by in the face of the mood for a fight, the number of unions backing a 24-hour national strike grew.

But Bob Hawke and the ACTU worked to undermine and deflate the momentum for action. Hawke managed to delay the date of the national stoppage until a special unions conference in July, meaning Victorian unions went ahead with their 24-strike on their own. Nevertheless it succeeded in shutting down trains and trams, closing factories and restricting services like electricity and telecommunications.

But even in Victoria, it was clear the union officials were less than enthusiastic about the strikes. Trades Hall failed to call a rally to bring union members together on the strike day. Some union members showed up in Melbourne city centre confused by the lack of activity.

It was left to far left groups including the Maoists and the International Socialists to organise a demonstration, albeit one much smaller than it should have been.

A national strike was eventually held on 12 July. But the delay allowed some unions to go back on earlier announcements that they would call members out to join it.

On top of this, the strike was called on a Monday, meaning some unionists just took a long weekend. The refusal to call demonstrations on the day was repeated, except in Newcastle, Wollongong and the ACT.

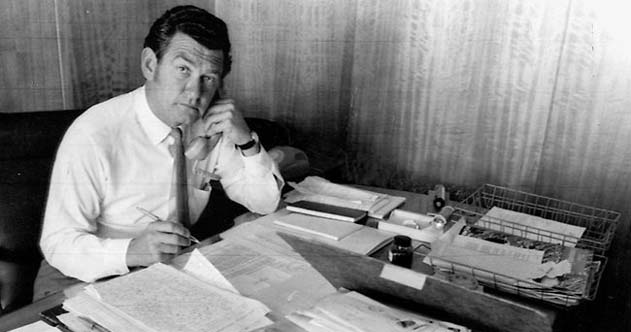

To top it all off, without any images of mass demonstrations to play in the media, Bob Hawke allowed himself to be filmed playing tennis, driving home the message that the unions weren’t serious about a strike campaign to defend Medibank.

While the strike campaign petered out, there was a continued push to maintain activity around Medibank. The union action helped give students the confidence to hold demonstrations against education cuts that were some of the biggest since the Vietnam War.

The pressure for an industrial campaign to save Medibank was also a clear indication to Hawke of the popularity of the scheme. Without this knowledge, he may not have reinstated it under the banner of Medicare in 1984.

The 1976 strike showed that we can’t rely on the union leaderships to call the industrial action needed to fight the Liberals.

It was only rank-and-file pressure that pushed union leaders into calling the Medibank strikes. Even left-wing officials like Halfpenny initially opposed action.

The reluctance of Hawke and others in the union bureaucracy to fight for Medibank demonstrates the ingrained conservatism of the union officials.

But the unions’ potential power to lead an industrial fight against the conservative agenda persists. It was clear at the Unions NSW delegates meeting in June and the nationwide Bust the Budget rallies that there is popular support for industrial action amongst rank-and-file unionists.

But it will take much stronger rank-and-file pressure to push the unions to take action.

The co-payment is a direct attack on one of the pillars of Medicare. The unions have the opportunity to capitalise on the hatred for the government and make this fight theirs.