The Australian economy’s dream looks to be over as the mining boom runs out of steam and living standards are squeezed. Peter Jones takes a closer look.

It was a “good outcome” according to Joe Hockey. Australia’s GDP growth came in at 0.5 percent for the December quarter; in line with expectations. According to the Treasurer, “Australia is still performing well by international comparisons”.

But beneath the headline GDP figure, the Bureau of Statistics also reported a decline in real gross domestic income, measured per person. Unlike GDP, this takes into account the fact that imports have become more expensive relative to exports, and the effect this has on how many commodities we can buy with each dollar. On this measure, Australia was in recession for three quarters of last year, and may still be.

The immediate causes of the income recession, and the apparent end of the mining boom, have been widely discussed. The extraordinary expansion of the Chinese economy has underwritten 23 years of uninterrupted GDP growth in Australia.

The global economic crisis passed this continent by because it had the right rocks and gases in the right places. It still does, but the investment boom has raised capacity enough to satisfy Chinese demand, which is itself weakening as growth in China also slows.

Now as commodity prices crash down to more “normal” levels (or lower) investment in new mining capacity is plummeting. Because it takes a long time to build mines and gas fields, some projects which were started when prices were higher are only now starting to produce output—pushing up GDP. But companies are getting less for each unit they sell, which tends to push down their income.

The iron ore price for instance has halved in the last year, dropping below $60 a tonne in March. And there are many fewer job vacancies in the resources sector because digging up and shipping out raw materials from existing mines is much less labour-intensive than building them (and the associated infrastructure) in the first place.

The lower cost producers of iron ore—BHP and Rio Tinto—are ramping up production to win market share from their competitors, adding further downward pressure to prices. This may lead to bankruptcies and job losses at some of the mines with less concentrated ore deposits or higher transport costs.

The Reserve Bank hopes that keeping interest rates low will stimulate growth and employment in other sectors. In February they cut interest rates to a record low 2.25 per cent, and most economists expect them to cut rates further.

This strategy has not really worked so far, either in Australia or the other advanced capitalist economies (where interest rates are near or below zero). Here, lower interest rates might have boosted residential construction, house prices and the stock market, but not much else. According to Deputy Reserve Bank Governor Phillip Lowe “it is difficult to escape the conclusion that changes in interest rates are not affecting decisions about spending and saving in the way they might once have done”.

The fall in prices for resources is also hitting the Federal budget. The Treasurer has stopped talking about a ‘budget emergency’ because the government has been forced to step back from implementing some of its most unpopular policies, for now. But the decline in the terms of trade (and its effect on revenue) has already been much larger than Treasury forecast. This makes the Coalition’s failure to sell its austerity agenda a serious concern for business, who had hoped for corporate tax cuts during this government’s term.

Squeeze on living standards

The income recession has also hit wages and employment. As usual, business wants the working class to bear the brunt of the economic downturn, as they move to protect their profits. Unemployment is now 6.3 per cent; just below the highest in 12 years (recorded in January) and a worse figure than for the US or the UK. It’s 20.3 per cent if we count everyone who wants more work. The paltry 2.5 per cent growth in wages last year was cancelled out by inflation (also 2.5 per cent).

Although they’ve made a small concession on pay for the military, Abbott and Abetz want to lock-in real wage cuts for the public service for the next three years, and are going after jobs. They’re offering less than 1.4 per cent per year to workers in the Department of Human Services and just 0.8 per cent to the Tax Office. And one in five public servants in the CSIRO can expect to lose their job over the next two years as the workforce is cut by 1300. Staff at Human Services and Veterans’ Affairs have voted overwhelmingly for industrial action, and ballots are planned at the Tax Office, the CSIRO, Agriculture and Employment.

Bosses in the private sector also want to take advantage of the weak labour market, and have been campaigning hard for changes to penalty rates and the awards system. It’s no coincidence that agreements for over one million workers are scheduled to be settled this year, including at Woolworths, Coles, the Commonwealth Bank and Telstra.

At the moment the government is too weak politically to go after penalty rates, and has instead announced a wide-ranging Productivity Commission review into industrial relations. This will almost certainly make business-friendly recommendations which the Coalition can use as ammunition later. The rallies called by the ACTU in response were an important indication of willingness to resist this agenda.

In the construction sector, where economic conditions are stronger (but worsening), the CFMEU have succeeded in extracting 5 per cent annual wage increases from around 200 contractors. This comes after a long industrial campaign against one of the companies involved (Boral) which included strikes and blockades. In spite of a legal challenge by Boral, and threats by the Liberals to change the building code to effectively ban companies from winning government contracts if they concede too much to workers, the CFMEU’s militant tactics worked.

Nevertheless, in the current economic climate, at many workplaces concerted industrial action will probably be required just to stop job losses and real wage cuts.

Profit rates

The deeper reason for the current malaise is that Australian capitalism is suffering from weak and falling profitability. Karl Marx argued that the best measure of this was the rate of profit. The underlying rate of profit measures how much value is available for capitalists to invest (or spend on their personal consumption) relative to the value of their assets.

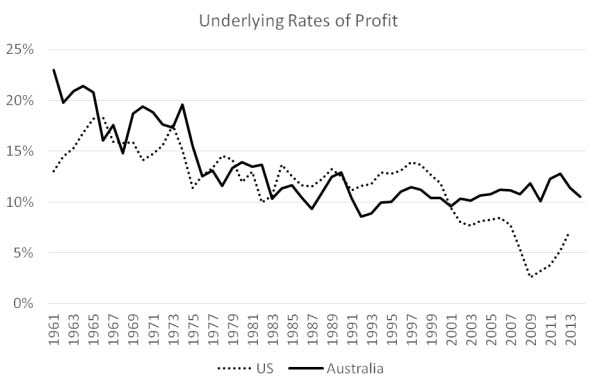

The graph above compares rates of profit in Australia and the US, based on national accounts data translated into a Marxist framework. We can see that, during the 2000s, the two rates of profit went in different directions.

The graph above compares rates of profit in Australia and the US, based on national accounts data translated into a Marxist framework. We can see that, during the 2000s, the two rates of profit went in different directions.

Spurred on by the mining boom, the Australian rate of profit increased quite steadily, while the US rate of profit fell catastrophically. But in 2013, as the mining boom came to an end, the rate of profit in Australia started trending downward quite sharply, while the rate of profit in the US has been recovering.

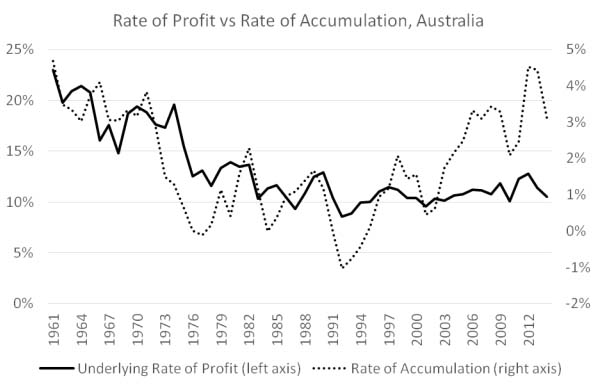

This has had major consequences for investment. Graph two compares the rate of accumulation in Australia with the underlying rate of profit. Generally, the underlying rate of profit determines how much capitalists invest relative to the value of their assets (the “rate of accumulation”); and, ultimately, the rate of investment determines how quickly output and employment grow. But the resources boom disrupted this relationship, as investment poured in lured by the possibility of super profits in the future.

With the super profits in mining now gone, investment is crashing back down towards levels more consistent with the low rate of profit.

The low rate of profit, in Australia and elsewhere, is not something which can be easily reversed.

The low rate of profit, in Australia and elsewhere, is not something which can be easily reversed.

Historically, major increases in the rate of profit have only come about due to major devaluations of capital which can be caused by economic crises, and the widespread and needless human suffering this brings. This has not happened since the Second World War in Australia, and the evidence we have suggests widespread devaluation has not happened elsewhere either (despite the crisis).

Other ways to boost profit rates include holding down wages, extending working hours, having people retire later and cutting government spending. These are part of the ruling class’ agenda throughout the advanced capitalist economies.

We must resist these attacks, but unless we get rid of capitalism itself they are going to keep coming.