The Magna Carta has been a symbol of basic rights for 800 years—but those rights were won through struggle and rebellion writes Tom Orsag

The 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta (or Great Charter) between King John and his rebellious Barons will be celebrated throughout the English-speaking world this month as the beginnings of the “rule of law”.

Tony Abbott described it as the “foundation stone of our democracy”, in launching commemoration events in Canberra.

But our democratic rights are the product of continual struggle, not some ancient British law in place from time immemorial.

What led to its signing was rebellion against the King. And over those eight centuries the Charter has been a source of inspiration to many further rebellions in Britain and around the world.

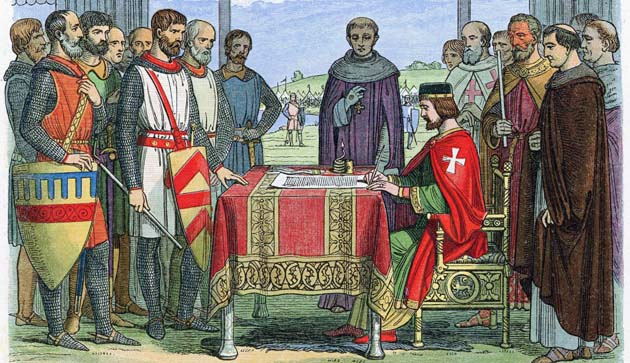

The Magna Carta was a product of the demands of feudal landlords, who forced the King of England to sign a document limiting his powers. The document, forced on King John by open civil warfare, established the right for some form of trial, and rights against arbitrary arrest and detention by the King’s men.

The original document was largely about dividing wealth and privileges among the existing feudal elite. Even the rights in Magna Carta for “free men” did not apply to fully 85 per cent of the population. However, the document was taken up later by subsequent revolutionary movements to press their own demands for greater freedom.

The revolt and the signing of the Charter were not a peculiarly British event of the medieval era, as some would have us believe.

In the same period charters of liberties were “granted” by European Kings and Queens in Leon and Aragon (modern Spain), at Constance, to the Lombard League of northern Italian towns, in Naples and Sicily, in towns in north-western Belgium like Ghent and even in Hungary.

The Italian cities of the time were burgeoning centres of economic growth and political self-government, expressed in charters that recognised their right to exist. There was a German saying, “Town air makes you free”.

The City of London was also moving more and more along these lines and had its own clause in the Magna Carta.

Any cities and towns in Europe were very small at the time. The overwhelming bulk of the population lived and laboured on the land, and were classed as serfs, legally controlled by the local Lord of the Manor.

King John, while no different to his European contemporaries, established reputation as crude, rapacious and venal.

When one of John’s Irish barons refused a summons to court in 1207, his wife and son were jailed and starved to death. Shortly after, 27 Welsh hostages held by the King were executed, when their baronial fathers refused to display grovelling loyalty to John.

Whereas the lords financed and cleared new lands and were the driving force in the spread of the some improvements to agricultural technology like the first early form of mechanisation, the water mill, the King was trying to expand his lands in England and France by plunder.

The King’s taxes impinged on the Barons’ and Lords’ own ability to accumulate wealth.

The decade-long reign of Richard I, immediately before his brother John became King in 1199, saw more money extracted from England’s taxpayers than any previous ten year period.

This included money for the Crusades, “and the methods he used to raise it set new standards in royal rapacity”, according to Geoffrey Hindley, in his A Brief History of the Magna Carta.

King John lost the French parts of his Kingdom in 1214, and along with them the respect of his English Barons. Not only had he imposed huge increases in taxation but the money he had raised for his wars in France was now wasted.

By April 1215, a civil war had begun against King John. The insurgent barons seized the City of London. They had joined forces with a Welsh nationalist uprising, triggered by John’s execution of the 27 Baronial sons.

The English rebels offered the Scottish King control of northern England. Out-manoeuvred, out-flanked and fighting on more than one front, King John was forced to negotiate, and signed the Magna Carta in June.

He then proceeded to re-open the civil war a few months later. Pope Innocent III weighed in on John’s side, saying the Magna Carta was null and void because John had signed it “under duress”.

King’s John premature death in October 1216 saw the Magna Carta re-issued in the name of the new King, along with the “Charter of the Forest”, limiting the King’s claims to areas near Royal woodlands. The forests in those days were a valuable source of wood for heating and cooking, game as food and herbs for medicine.

In the subsequent re-affirmation by future kings, the Magna Carta established that no one could be arrested without trial, not even by the King, as well as the right to a speedy and fair trial.

The Barons, in arguing for their own rights, had inadvertently opened the door for the rights of every “free man”.

Revolutionaries

These principles were taken up again in 1628, when the Petition of Right was drafted to limit the authority of the autocratic Charles I.

The Parliament refused to authorise taxation for war by Charles I, unless he agreed to the demands in the Petition.

Parliament fought under the banner of the Magna Carta.

Edward Coke, dismissed by as Chief Justice of the King’s Bench after a clash with the King over the extent of royal prerogative, argued that Magna Carta was still in force. The King instead insisted on his own authority to imprison those who refused to hand over taxes raised without parliament’s consent.

That argument led to Civil War in England in 1642, and escalated into a revolution that saw Charles lose his head to a Parliamentary executioner in January 1649.

This was a radical step which challenged the age old ideas that Kings had a special link to God and governed by virtue of the “Divine Right”.

Underlying this was the growth a new class of capitalists in the towns, especially the City of London, who produced wealth in a quite different way to the old feudal lords.

The modern idea of the “rule of law” dates from this period. The new capitalists wanted a clear written framework of laws.

They were opposed to the idea that laws could be over-ridden on the decisions of the King or rival courts, as their decisions could be arbitrary and uncertain.

Capitalists required certainty that their investments would be protected and that contracts would be honoured. They needed regulation of the competition between them, lest the competition get out of hand.

More radical groups involved in the English Revolution, such as the Levellers and Diggers, also used the Magna Carta to argue for forms of economic and as well as legal equality.

They sought to extend the new freedoms being won by the emerging capitalist class across the whole society arguing for, “the right, freedome, safety, and well-being of every particular man, woman, and child in England.”

The Leveller leader John Lilburne cited the Magna Carta while he was on trial and refused to kneel while in the dock.

Gerrard Winstanley, of the Diggers, referred to it when they occupied vacant land in 1649 to grow their own food.

The American War of Independence from England in 1776 also drew its legal inspiration from the Magna Carta, as a revolt of “free Englishmen” with legal rights against a plundering King.

When the English working class movement of the 1830s and 1840s tried to express their rights in a “People’s Charter” they drew the idea from the Magna Carta.

Struggle for rights

Our rights are not protected by some ancient law—they constantly have to be fought for and re-won.

It was “illegal” in Melbourne until May 1969 to hand out leaflets against the Vietnam War, due to a City of Melbourne by-law. A campaign involving mass arrests for defying the ban, including the arrest of the deputy leader of the Labor Party Opposition, won that right.

Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Peterson banned political street marches in 1977, until a campaign of mass defiance won back the right. Even today there are still police attempts to attack the right to protest and dissent.

The Magna Carta still has modern resonance as “the rule of law” is undermined by governments worldwide seeking to restrict basic human rights in the name of “fighting terrorism”.

It has been used by opponents of Bush and Blair’s use of rendition and torture after 9/11 in Guantanamo Bay and in third country “black site” torture centres.

The US Supreme Court declared torture in Guantanamo “unconstitutional” in 2008, citing the Magna Carta.

Harking back to King John’s autocratic style, George W. Bush told his National Security Council in January 2003, “I do not need to explain why I say things. That’s the interesting thing about being President.”

Tony Abbott has extolled Magna Carta as establishing that, “decency, civilisation, human rights utterly depend upon the rule of law”.

But as he increases police and ASIO powers, imposes detention without charge through preventative detention orders on terror suspects and extreme measures against refugees, we can point to his hypocrisy about his beloved “rule of law”.

We will never be equally legally when society is so sharply divided economically, which is more and more the case with the growth in inequality in the neo-liberal era.

While it was convenient for the capitalist class to champion freedom against the old aristocratic order, now that they rule they need to restrict the freedoms of the working class below them.

Strikes and working class action remain either criminalised, or possible only after clearly near impossible legal hurdles. The fight for equality remains bound up in the fight for equality before the law.