Privilege theory weakens opposition to oppression, because it misdiagnoses its source and portrays those who aren’t oppressed as incapable of fighting it, writes Lucy Honan

Privilege theory has become a common-place starting point for people who want to respond to oppression. We have “Dear white people” the movie, “check your privilege” guide books for allies who want to “decolonise” themselves, online privilege calculators and blogs on how to call out privilege. It even dominates diversity workshops in workplaces.

The “call outs” of privilege are an attempt to make it clear that the oppressions are alive and well and need our attention—and socialists most certainly agree.

While John Howard was declaring sexism a thing of the past, reports of domestic violence in Victoria increased 72.8 per cent. Attacks on Muslims are frequently reported and the bashing of a transwoman at the Newtown hotel is a reminder of the persistence of bigotry and homophobia.

But beyond that agreement, privilege theory is a problem.

It fundamentally misdiagnoses the sources of oppression, and fatally disorientates and disarms people who otherwise should be leading the struggle against racism, homophobia, sexism, and oppression.

Privilege theory

There are different schools of privilege theory, but the common themes are these: in any area of oppression you are either penalised or privileged. And if you are privileged, that is an unearned, usually unconscious, unfair advantage that you have.

Peggy McIntosh, perhaps the mother of privilege theorists, famously wrote a list of 46 examples of white privilege she experienced. She has regularly updated the list, to include the privilege of being reflected in the media, of not being likely to be stopped and searched, of not having to wonder if you didn’t get the job because of your last name.

Finally, because of the unfair advantage, that very privilege is held to disorientate and infect a person’s world view, so that they have a vested interest in recreating the discrimination and oppression to maintain their position of privilege.

Privilege theorist and diversity consultant Frances Kendall argues, for example: “Any of us who has race privilege, which all white people do, and therefore the power to put our prejudices into law, is racist by definition, because we benefit from a racist system”.

Instead of arguing that it is unfair for women to receive almost $300 less than man a week on average, the starting point for some privilege theorists is that it’s unfair for a man to receive $300 more. It directs our fury at husbands and men, as opposed to, for example, the lack of government services provided by Minister Scott Morrison, where women are lumped with the housework and unpaid child rearing.

The strategy for privilege theorists is to make privilege visible, to call it out, so that the privileged “do work on themselves” to become more self-conscious and self-aware.

This dovetails with lifestyle politics by focusing on interpersonal oppression.

Problems with Privilege theory

Privilege theory misdiagnoses the source of oppression.

Identity politics and privilege theory have their intellectual roots in postmodernism. Most famously, Michel Foucault argued for a rejection of any totalising theory, including Marxism, in favour of looking at the world through subjective positions, rejecting the idea of any single explanatory discourse or source of oppression. He argued that:

“Neither the caste which governs, nor the groups which control the state apparatus, nor those who make the most important economic decisions direct the entire network of power that functions in a society.”

Most privilege theorists assert that there is systemic gender and racial oppression. But they reject the idea they are rooted in capitalism; rather, oppression is seen as cut adrift from any root cause. Forms of oppression exist autonomously from the economic system, and from all other oppressions.

The immediate experience of oppression can seem to confirm this. It is not the long arm of the law that reaches into our cots when we are babies to dress us in pink or hand us a doll, but our parents.

The humiliations and constricting expectations feel like they are come from everywhere—the church, the state, the family, the media, the school, the workplace, and often from people very close to us.

But most of the apparent agents of oppression derive little or no benefit from it.

Mothers or other women, whose comments often trigger body image issues, are not privileged. Virulently homophobic kids are often the most insecure. Working class people who hold racist ideas about refugees and Muslims are propping up a Liberal government that could hardly be more opposed to their interests. Research in the US shows that the areas of greatest inequality between black and white workers also have the lowest wages for whites.

On the other hand there clearly are some agents of oppression who are more powerful than others. Governments and the wealthy have a much greater capacity to wreck people’s lives.

This is clear in the racism of Aboriginal community closures and assimilation projects going on ruthlessly around the country, the offshore detention centres and endless flag-clad press conferences about threats to our borders.

Intersectionality is supposed to account for this difference by looking at how class privilege intersects with race and gender privilege.

But again this leaves us at the level of static description of interpersonal experiences. Oppressions are not simply held in place by all those with the “privilege” not to share them.

It is not simply Joe Hockey and Abbott’s personal experiences as privileged white males that make them so destructive. It is the political interests they serve, and their concern to advance the needs of capitalism.

Yet Foucault argued that, “there is no single locus of great Refusal, no soul of revolt, or pure law of the revolutionary. Instead there is a plurality of resistances, each of them a special case.”

This means refusing to differentiate between the importance of any particular struggle, and refusing to concentrate resources at the source of oppression.

For example, at a recent anarchist book fair, an argument that the fight against Abbott was crucial for fighting community closures and refugee racism, got a “privilege check” for scapegoating Abbott for that activists’ own “white supremacy”! Instead there were suggestions to renounce citizenship privilege and support autonomous collectives.

Similarly, at Sydney University an Ethnic People of Colour Collective established itself in 2013 with a view that those who aren’t oppressed all have a stake in perpetuation oppression.

One of the main conclusions they drew from this was that the Anti-Racism collective was “racist” because it involved white people in the fight for refugee rights. Instead of focusing on our rulers their target was a generalised “white culture”, which meant predominently focusing on discussion of personal experiences.

The produces profound disorientation, with the potential for dedicated anti-racists to funnel their anger into call outs and privilege checks when they could be organising to fight Abbott and the system.

Marxist theory of oppression

Far from the caricature of Marxism minimising or deprioritising issues of oppression, it helps us to understand oppressions as fundamental to the operation of capitalism.

Marxists don’t ignore interpersonal dynamics. But we need to look below the surface to the social, historical and economic dynamics that underpin them to make sense of how oppression works.

If we apply this to women’s oppression, we can see that beneath the many ways we experience oppression, the social and economic forces that organise our society have laid the foundation for inequality between men and women.

One of sexism’s main functions is to enforce the nuclear family, and women’s role with the major burden of child rearing. This means business does not have to pay the costs of bringing up the next generation of the working class, but instead gets this work done for free.

The Productivity Commission report into childcare indirectly revealed just how much unpaid childcare families, and mothers in particular, are doing.

Only 38 per cent of children are in formal childcare, and of total formal childcare costs, the government only pays 37 per cent of costs, which is about $7 billion dollars a year. So the amount of totally unpaid time women—and it is mainly women—spend doing this essential work is enormous.

For some women, the burden of childcare means it is impossible to return to work, whether because of the difficulty of finding and maintaining childcare, or the cost. For others it means the misery of missing out on a child’s early years if balance between work and being at home proves impossible.

This is all the result of government and business’s refusal to provide free, accessible childcare, or adequate paid maternity leave.

The socialisation of women and girls as carers, whose main productive role is to care for children and the home, can be traced historically to the birthpangs of capitalism. The working class family was nearly destroyed by the brutish conditions and hours of work in the new factories. This meant they were simply unable to care for the next generation, which threatened the supply of labour. So the ruling class encouraged women to stay out of the workforce and focus on bringing up children.

In Australia there was a very deliberate establishment of the family wage paid to men—enforcing women’s position in the family, and their childrearing and reproductive role.

Socialists look to mass struggles as the solution, and in particular the power of organised workers, because they have both an interest in fighting oppression and also the ability to get rid of the capitalist system that produces it.

Oppression benefits capitalism and the rich, not working class people.

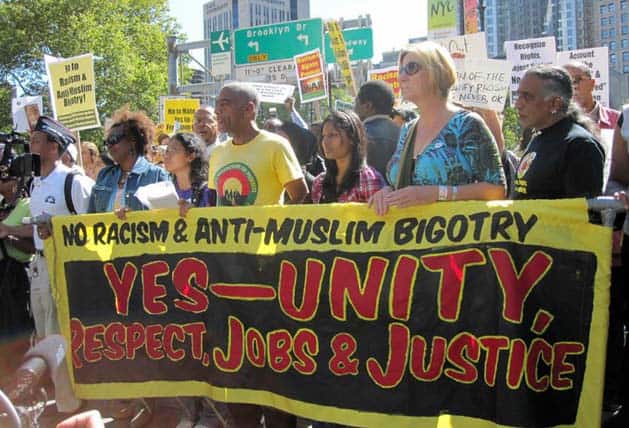

This can be seen in any major struggle, which breaks down racist, sexist and homophobic ideas as a barrier to the unity amongst workers needed to fight.

For instance the support for the workers’ picket line at Hutchison from the Redfern Aboriginal Tent Embassy and equal love activists, who took a collection for the workers at their rally, has reinforced opposition to racism and homophobia amongst the workers and built a spirit of united resistance.

It is through such unity against oppression, and the capitalist system that produces it, that liberation is possible.