The new TV series Chernobyl has reawakened interest in the shocking nuclear disaster. Michael Douglas looks at the lessons and why nuclear is no solution to climate change

On 26 April 1986 a nuclear power reactor exploded at Chernobyl in Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union. Radioactive material equivalent to 400 Hiroshima bombs was hurled into the atmosphere.

Authorities failed to organise evacuations and lied to emergency workers sent to contain the disaster, and to thousands of volunteers who poured into the region to help. These shocking events are examined in the new television series Chernobyl.

The scale of the Chernobyl catastrophe has never been officially acknowledged. Soviet authorities tried to cover up the scale of the disaster, and as a result the number of deaths from radiation exposure is still unclear.

Academic Kate Brown spent four years examining numerous studies and archival material for her new book Manual for Survival. She estimates it caused between 35,000 and 150,000 fatalities. After Chernobyl, in areas contaminated by radioactive material, people “fell ill from cancers, respiratory illness, anaemia, auto-immune disorders, birth defects, and fertility problems two to three times more frequently in the years after the accident than before”, she wrote.

The Ukrainian government alone still pays compensation to 35,000 people whose spouses died as a result of the disaster.

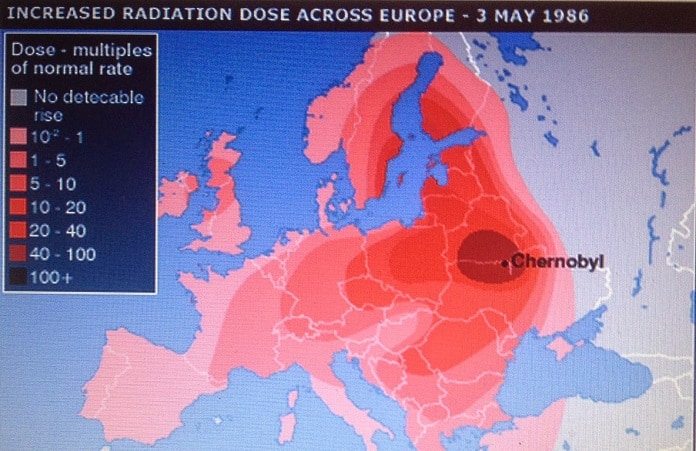

The effects are ongoing. Most of the radiation from Chernobyl hit Belarus. Today 20 per cent of its farmland is permanently unusable.

Contaminated soil was found as far as Corsica in the Mediterranean. In Britain almost 9000 farms were placed under restriction after rain dropped material from Chernobyl into the soil. The last restrictions were not lifted until 26 years later.

The Soviet government issued no warnings. The world only learned of the disaster when Swedish authorities detected increased radiation in the environment two days after the explosion.

Stalinist Russia

These events at Chernobyl and their attempted cover up were another nail in the coffin of the Soviet Union.

Some reviews of the new TV series have complained that it treats the Soviet Union unfairly and that the agenda of series writer Craig Mazin, who previously worked on comedies like The Hangover Part II, is to smear the Stalinist system in an effort to undermine the idea of socialism as an alternative to capitalism.

Even if these criticisms are accurate, they are secondary. There is nothing about the Stalinist dictatorship in Russia that the left should defend.

The Soviet Union was founded by a genuine workers’ revolution in 1917. But Joseph Stalin led a counter-revolution in the 1920s that crushed working class organisation and resistance, turned the country into a dictatorship, and imposed a program of forced industrialisation to compete with the West.

This meant all industry in the Soviet Union was owned by a state over which workers exercised no democratic control. The system relied upon the accumulation of capital by, and in the interests of, a new ruling class through the ruthless exploitation of workers. By the time of Chernobyl, this system of state capitalism was in a deep economic crisis after decades of stagnation.

French liberal theorist Alexis de Tocqueville famously observed the most dangerous moment for a bad government is when it begins to reform. The Soviet ruling class was split about the way forward. President Mikhail Gorbachev had come to power in 1985 representing a section of the ruling class that wanted to open the economy to the market and integration into the world economy—a process known as “perestroika”.

But Gorbachev was soon locked in a power struggle with more conservative sections of the ruling class determined to carry on as before. In order to help push this restructuring through, Gorbachev signalled the limited opening up of political freedoms, known as “glasnost”. These moves only increased the appetite for more change.

The Chernobyl disaster accelerated this process. Millions of people lost faith in the Soviet system and its claims of technological superiority over the West. In 1989 a wave of miners’ strikes swept Russia for the first time in decades. Revolutions soon overthrew the Soviet Union itself.

Not safe

Chernobyl was the world’s worst nuclear accident—so far.

The United States’ worst nuclear disaster was in 1979. Mechanical failures led to a partial core meltdown in one of the reactors at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station in Pennsylvania.

In the United Kingdom, there were 1767 leaks, breakdowns or other safety “events” at nuclear power reactors between 2001 and 2008.

The French government is required to announce all nuclear incidents. These have numbered up to 800 per year. In 2009 a heatwave shut a third of French reactors because rivers became too hot to act as a coolant. As the Earth warms due to climate change, the impact on nuclear safety will be even greater.

In 2011 Japan faced nuclear meltdown. Explosions at its Fukushima nuclear power plant, after an earthquake and tsunami, released radiation into the atmosphere.

Japanese Prime Minister at the time, Naoto Kan, has said that in a worst case scenario, the evacuation of Tokyo’s 30 million people would have been necessary.

Both the Fukushima and Onagawa nuclear power plants have a history of radiation leaks, damaged reactors and cover-ups. But Japan’s government let them carry on operating. And it still hopes to increase reliance on nuclear power, after many plants closed following the disaster.

The picture is similar elsewhere. India has commissioned 21 nuclear power reactors by 2031, many of them already under construction. China has 45 nuclear power reactors in operation, about 15 more under construction, and plans to commission another two every year for the next two decades.

In Australia, Coalition MPs are again campaigning to develop nuclear power, with another official inquiry now launched. The main purpose of this is to legitimise further uranium mining, with Australia holding the world’s largest reserves. The Yeelirrie uranium mine in WA was recently given the go ahead by the state’s Supreme Court.

Clean power?

To justify this madness the nuclear industry has claimed green credentials, arguing that electricity produced by nuclear power is carbon neutral. This means it doesn’t generate carbon dioxide and is therefore a way to combat climate change.

On the surface this is correct—the nuclear reactions that take place inside a reactor to generate power do not add carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. However, nuclear power reactors require a cycle of mining, transport and waste storage that generates huge amounts of greenhouse gases.

A Friends of the Earth report in 2004 took into account the carbon dioxide released by the building of a nuclear power reactor, the mining and transport of uranium, the processing and then further transport of the nuclear fuel, followed by the long-term storage of the spent radioactive waste. It showed that nuclear power produces “about 50 per cent more global warming emissions than wind power”.

Olympic Dam mine located near the town of Roxby Downs north of Adelaide is the second biggest uranium mine in the world. It is the region’s largest producer of carbon dioxide and consumes a quarter the state’s electricity.

It also has a terrible record for destruction of the local environment and poisoning the surrounding area with radiation.

Converting the world’s energy generation from fossil fuel technology to nuclear power couldn’t happen quickly enough to produce the immediate reduction in carbon dioxide emissions that are needed. A nuclear power plant takes 15 years to build.

Nuclear power is not part of the solution to climate change—it is part of the problem.

Investment should be directed towards sustainable, green and safe energy instead. And workers should not have to choose between their jobs and living standards on the one hand and tackling climate change on the other. Spanish mining unions recently won a €250 million deal which will see the closure of nearly all coal mines in Spain and the retraining of effected workers as part of a just transition.

The environmental claims of the nuclear industry look even shallower when you consider the huge amounts of waste produced, much of it lethal for hundreds of thousands of years.

There are serious doubts about the ability to store this waste safely. The British agency responsible for storage proposes burying the material up to a kilometre underground. Yet its own advisers are worried that the containers used could rust in less than 500 years.

The Observer newspaper pointed out that: “Almost 90 percent of Britain’s hazardous nuclear waste stockpile is so badly stored it could explode or leak with devastating results at any time.”

So much nuclear waste exists in the United States that an entire mountain has been hollowed out to store the material. Existing waste would more than fill the mountain and a new alternative must be found.

These are not even the worst aspects of nuclear power.

“Civilian” nuclear power programs arose to produce plutonium for nuclear weapons. When the Sellafield nuclear power reactor opened in the United Kingdom in 1956, its primary role was to produce plutonium for British bombs.

The same is true of early reactors in the US, France, Russia and China. Of the 10 nations to have produced nuclear weapons, eight have nuclear power reactors. And both Israel and North Korea used the pretence of nuclear power programs to amass plutonium.

Chernobyl reminds us of the day we almost lost Europe. It examines how class divisions determine who is affected by disasters and how badly. It should also remind us that Stalinism was never an alternative to capitalism. It also shows there is no safe way to generate nuclear power or store radioactive waste—and that nuclear power is no solution to climate change.