A defiant strike at the Weipa mine against individual contracts sparked a nationwide strike wave that halted a push to deunionise the country, writes Jacob Starling

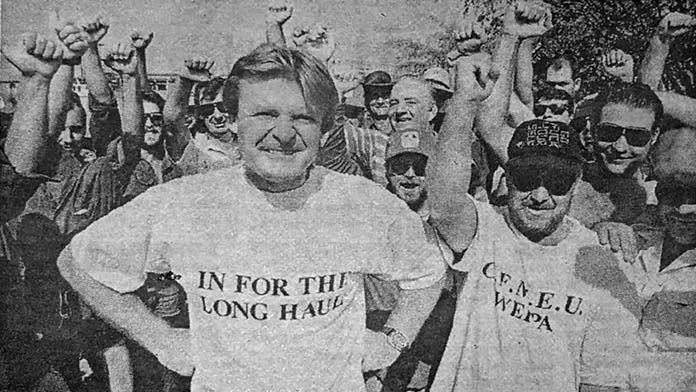

On 13 October 1995, 78 CFMEU workers at Weipa, a remote mining town in Far North Queensland, began a defiant strike that would become a nationwide flashpoint.

Unionists dramatically blockaded the wharves with their tiny fishing boats, demanding that they receive the same pay as non-union workers. Five bulk ore carriers were forced to anchor offshore, unable to load $6 million worth of bauxite ore.

Their employer, Comalco, a subsidiary of mining giant CRA (now Rio Tinto) had a ruthless record of deunionising workforces. However, when they tried to deunionise their bauxite mine in Weipa they were met with fierce resistance from a militant minority of workers.

Within weeks, the dispute had become a national industrial campaign, triggering a thousands-strong strike wave in solidarity.

Thirty years on, the story of the Weipa dispute is a powerful demonstration of how rank-and-file workers can win against corporate Goliaths through determined resistance.

The strike at Weipa was sparked by the bosses’ attempts to replace union-negotiated awards with individual contracts. This was part of a decades-long bosses’ offensive against the right to organise collectively for better wages and conditions.

Union agreements rely on the combined power of the workers to push up wages and protect workers from cuts.

Individual contracts are negotiated between bosses and individual workers. They are designed to fracture the workforce with different wages and conditions. This makes collective struggle harder.

The pro-business policies of the Hawke-Keating ALP government, and the decision of union leaders to go along with them, weakened union strength and encouraged businesses to try to introduce individual contracts.

In 1993, Prime Minister Paul Keating promised a round table of company bosses that he would replace awards with enterprise bargaining agreements (EBAs).

These would be negotiated collectively with unions, like awards, but at an individual company level instead of across an industry. They were designed to bind workers’ wages to productivity instead of the cost of living.

In effect, this meant that workers’ wages were dependent on delivering bosses higher profits. Pay rises would require trading away conditions or accepting job cuts. Enterprise bargaining also placed severe restrictions on the right to strike, limiting industrial action to narrow bargaining periods every few years, making it much harder to defend wages and conditions.

This attack on workers’ rights was justified by appeals to the “national interest”, code for the rights of Australian capitalists to maximise profits. The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) leadership eagerly promoted the EBA framework, arguing for cooperation between bosses and workers.

By accepting the need to improve business competitiveness, the ACTU and the ALP made it easier for companies to go one step further and try to get rid of unions altogether.

Deunionisation

CRA-Rio Tinto had been working to deunionise their sites since the mid-1970s. They argued that individual contracting was needed to cut costs, and workers would have to give up their union card if they wanted their employer to stay in business.

This started in earnest in 1986, when CRA began a five-year restructuring program on its New Zealand aluminium smelter. Non-union workers were offered higher wages and voluntary redundancies, bypassing the union entirely. The union leadership refused to take industrial action and, by 1991, the union there had all but collapsed.

CRA repeated this process at Hamersley Iron in the Pilbara, and at its aluminium smelter in Bell Bay in Tasmania. Despite the strong tradition of militancy at both sites, the union leadership again refused to take industrial action.

By the end of 1993 at Hamersley 90 per cent of workers had signed individual contracts and by July 1994 only 22 workers out of 430 were still unionised at Bell Bay.

Weipa

Comalco’s bauxite mine at Weipa was next in CRA’s sights. Comalco had already cut training and overtime pay in 1991. They also made a deal with the AWU, marginalising the more militant CFMEU. In 1994, Comalco began negotiating individual contracts with workers, offering them up to $20,000 above the union rate.

Workers “were starved onto them”, Nigel Gould, a worker at Weipa, explained. Getting any pay rise following the cuts to overtime pay effectively relied on accepting individual contracts.

Instead of going on strike, the AWU appealed to the Industrial Relations Commission for a pay rise. Their legal strategy failed and union membership collapsed. As a result, 80 per cent of the workers at Weipa left the union and signed individual contracts, attracted by the pay rise and additional benefits.

Non-union workers were promised better superannuation, extra annual leave, subsidised medical benefits and assistance for their children to receive a university education. However, without a union to hold them to account, the bosses at Comalco now had free rein to chip away at workers’ conditions.

There was a serious threat that companies nationwide would copy their example, decimating union membership and opening the way for a frontal assault on wages and conditions built up over generations.

It was a small, die-hard group of rank-and-file unionists who took up the campaign for equal pay. The 78 workers who walked off the job on 13 October were a minority of the workforce, but they were able to cause serious disruption to Comalco’s operations and galvanise the union movement nationwide.

When Comalco went to the courts to try to break their picket line, demanding that the union pay for the company’s losses, maritime and coal workers answered their call for solidarity.

On 8 November, 2000 unionists at the Blair Athol and Tarong coal mines in Queensland launched a 24-hour strike. Maritime workers on the River Embley, one of the bulk carriers held up by the workers’ picket at Weipa, stopped work for 24 hours.

By 10 November, 3000 workers were on strike at CRA’s coal and coke facilities across Queensland. Port workers nationwide refused to touch CRA coal. Five days later, the CFMEU announced a nationwide coal miners’ strike in solidarity with the Weipa workers. It was a fantastic demonstration of the power of strike action to shut down the country through the kind of solidarity action needed to win.

Weipa striker Nigel Gould said that they were “overwhelmed” with support. “Mining communities in every state and territory, and refineries, have sent letters and money. They’re supporting us all the way.”

The Wik people, local Indigenous Traditional Owners, backed the strikers, and gave them permission to launch their fishing boats from sacred sites.

Weipa also received a solidarity message from the Bougainville Freedom Movement, where CRA had the huge Panguna copper mine.

The surge in support forced the ACTU leadership to take a stand, announcing that unions in other industries were also preparing to take action against CRA.

ACTU Secretary Bill Kelty announced that he was drawing a “line in the sand” against individual contracts. However, despite the tough rhetoric, the ACTU offered to negotiate a settlement with Comalco instead of giving full support to the fight from below.

The strike wave reached its peak in mid-November. There was a nationwide strike of maritime workers and two days later 25,000 coal miners went on strike. There were 2000 miners so enthusiastic to support the workers at Weipa that they walked off the job 30 hours early.

Meanwhile, as soon as the ACTU got a whiff of a possible settlement, it called off the solidarity strikes. In late November they pressured the strikers at Weipa to go back to work and allow the ACTU negotiate on their behalf.

When the striking workers declared that they would not return to work until they had a written agreement from CRA promising equal pay, the ACTU threatened that they would be left on their own.

Very quickly, the IRC ruled in their favour. The Weipa workers won equal pay for equal work, back pay and the right to negotiate collective agreements through the unions. The government forced Comalco to drop its damages claims against the union.

A year later, when Comalco tried again to introduce individual contracts, the workers were ready. Unionists immediately went on strike, forcing management to withdraw the demand after just two days.

Legacy

The victory at Weipa shows that it is possible to fight and win against the bosses with a rank-and-file, militant approach.

Unionists were able to resist the pressure towards individual contracts. It was the courage and resilience of the workers themselves that won equal pay for equal work at Weipa, not the ACTU’s legal strategy.

When the Liberals under John Howard took power in 1996, they moved to make it much easier for businesses to use individual contracts. The Liberal’s Australian Workplace Agreements left a terrible legacy but they were never able to be used to break unions as initially intended.

Since then the acceptance of enterprise bargaining and the failure to fight to maintain wages and conditions has enormously eroded union strength. The right to strike is strictly limited, with massive fines for taking the kind of nationwide solidarity strikes that erupted to support workers at Weipa.

Labor continues to crow about the “national interest” and the importance of protecting profitability for the bosses. Its attack on the CFMEU was designed to weaken a union prepared to defy the anti-strike laws to win better wages and conditions for its members.

In the Pilbara, workers are still fighting to undo the damage wrought by 30 years of individual contracts. The anti-strike laws today mean the shackles are tighter on the unions than they were 30 years ago.

But the unionists should not give up. Unions have launched an effort to reunionise the mines in the Pilbara and have had some successes at BHP.

There was a setback in July when the FWC ruled that the Western Mine Workers Alliance had failed to demonstrate that a majority of workers supported unionisation at Rio Tinto as required.

But the success of the Weipa dispute is proof that individual contracts can be beaten through collective, militant action. Rio Tinto has been beaten before and it can be beaten again.