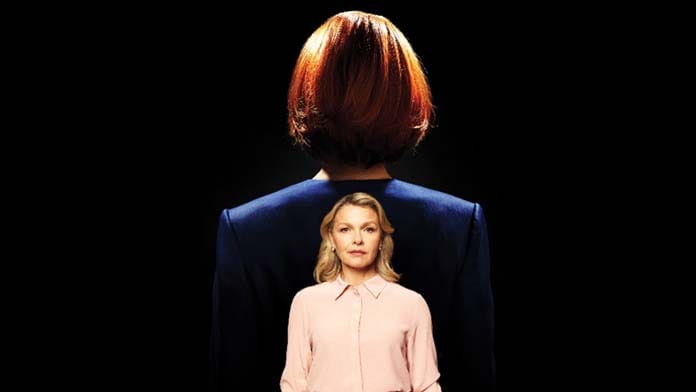

Joanna Murray-Smith’s play Julia, directed by Sarah Goodes, is a dramatic retelling of the events leading up to Julia Gillard’s famous 2012 “Misogyny Speech”.

While the play, starring Justine Clarke as Gillard, effectively portrays the sexism the first female Prime Minister endured, it falls short in capturing her political legacy.

The play presents Gillard as a feminist icon but glosses over the harm caused by her policies, including cuts to single-parent payments, anti-refugee policies and opposition to marriage equality. In doing so, Julia highlights the limits of identity politics and parliamentary strategies for achieving systemic change.

The central theme of the play is its emphasis on Gillard’s gender as a basis for political success. But this identity-based portrayal bulldozes over her participation in policies that harmed marginalised groups.

The play proudly declares the 543 acts of legislation passed under Gillard’s leadership as a great achievement. What it fails to adequately handle are the consequences of this legislation.

Gillard’s Labor government blocked marriage equality, cut funding to single parent payments and resumed Australia’s offshore detention scheme, simultaneously stoking racist fears of “boat people”.

These examples undermine the intended “girl power” message of the play and are a bitter reminder that simply having women in power doesn’t automatically equate to feminist or progressive outcomes. This preoccupation with representation rather than addressing the structural causes of oppression leads to stagnant reformism—if that.

Gillard’s defence of her policies, particularly in a scene where she justifies her actions under political pragmatism, reinforces the failure of her approach. There is a brief mention of her compromises in a scene where Gillard is frenzied as a result of the sexism she faces.

The actor’s panicked pacing alongside confused and repetitive muttering of the phrase “children overboard” (no, really) is followed by what is meant to be a rousing monologue about Gillard’s realism.

“Courage without power,” she tells us, “is just a figment”. Contrary to being the defence of political realism this was intended, it leaves the impression that Gillard’s focus on power at the expense of systemic change undermines any meaningful commitment to feminist ideals.

The scene serves as a reminder of why identity politics and electoral strategies are insufficient for achieving true social transformation.

Identity politics’ focus on lived experience is useful for raising awareness but is a dead end when it tries to form the basis of political strategy. By elevating individual representation as the goal, identity politics can fracture the working class along identity lines, weakening solidarity.

The play’s portrayal of Gillard as a feminist trailblazer is a form of tokenism which doesn’t challenge the capitalist system that perpetuates inequality. The same can be said of now Foreign Minister Penny Wong, who is complicit in the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Electoral strategies like that personified by Gillard emphasise reform within the capitalist system and the institutions of society, aiming for representation rather than transformation.

As a result, the play’s celebration of Gillard’s famous speech, delivered against then opposition leader Tony Abbott, feels shallow and opportunistic. Her speech targeted the misogynistic “boys club” culture in parliament as a clear enemy to gender equality.

But the way it is elevated, combined with the play’s continual reference to Kevin Rudd’s egomania and wry quips about her enduring interpersonal sexism in the name of “playing the game”, are meant to divert our attention from Gillard’s broader role in maintaining systems of oppression.

By contrast, class-based movements, through a dynamic process of democratic debate and mass direct action, seek to unite all oppressed people against the capitalist system itself, rather than merely aiming for better representation within it.

The fight against oppression is not simply important for those with direct lived experience of it. Capitalism as a system perpetuates various forms of oppression in an effort to divide us and undermine the collective effort needed for systemic change.

Successful movements of the past, including the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s and 1970s, built coalitions among the working class across identities and focused on both economic and social justice.

By the time the play culminates in Clarke’s own rendition of the misogyny speech in full, much of the illusion of Gillard as a feminist icon is lost. Julia falls short by promoting an identity politics that celebrates representation while ignoring the broader reality of oppression.

Without actually challenging the root cause of oppression, and indeed aiding in oppressive systems through her policies, Julia Gillard’s identity-based electoralism feels like “just a figment” of change.

By Caitlin Boyce

Julia is a production of the Sydney Theatre Company and runs until 19 October.