Today, ALP conferences are largely stage-managed media events, MPs speak to sound bites supplied by the party machine, and a pitifully small number of members participate in the life of the party.

That wasn’t always the case. There was a time when the party was riven by debates on big issues, when MPs staked out positions and fought for them, and when the party grappled with how to achieve socialism.

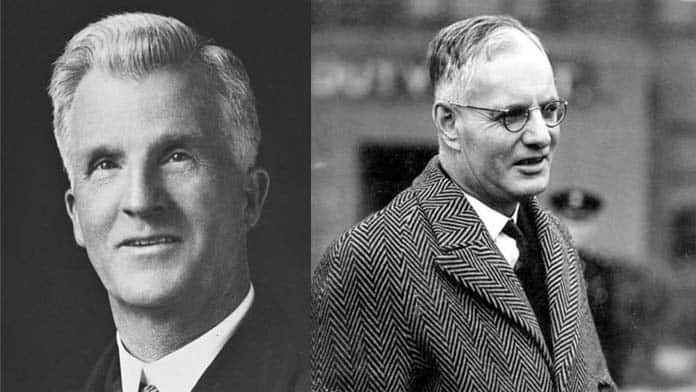

This new book by Liam Byrne, the ACTU historian, covers the making of Labor from 1876 to 1921. It does so by following the careers of two men later to become Prime Minister—James Scullin and John Curtin.

Both were born to Irish Catholic migrant families in the goldfields of Victoria, worked as journalists, were deeply involved with the union movement and devoted their adult lives to the ALP.

Byrne weaves their stories through some of the key debates in the movement, including the fight against conscription in World War One and the resulting expulsion of Prime Minister Billy “the rat” Hughes from the ALP, and the debate over the party’s adoption of a socialist objective in the aftermath of the war.

Scullin was on the right of the party and deeply religious. But a century ago that still put him well to the left of most Labor MPs today.

In his first tilt at parliament, in 1906, he put the case for the nationalisation of monopolies, the abolition of state parliaments and for union members to have preference when seeking state employment. In the 1916 conscription debate, he campaigned through the paper he edited, the Ballarat Echo, for a No vote.

Curtin was very much on the left. While Scullin’s socialism was something to be achieved in a long-distant future (he played a key role in ensuring that Labor’s socialisation objective, adopted in 1921, was similarly vague), Curtin cut his political teeth arguing that Labor should be taking immediate steps towards socialism through nationalising the means of production, distribution and exchange.

He imbibed much of his outlook from Tom Mann, the British union leader who arrived in Melbourne in 1902 and quickly became both Labor’s organiser and the dynamic element behind the Victorian Socialist Party.

Byrne has done valuable work in trawling through personal archives and the newspapers of the day. The detail brings the book to life and makes it a lively and accessible read.

Yet there remain some serious political gaps. Because the book is closely focused on the careers of two Labor men, it fails to place them in a broader context.

So the 1917 NSW general strike merits a scant paragraph, as does the Russian revolution. The Industrial Workers of the World and the Communist Party rate a passing mention. And then there are the questions that are simply left untouched.

Curtin and Scullin were from Irish Catholic families, but Byrne doesn’t discuss their views on Irish independence or how that intersected with their opposition to conscription at a time when Cardinal Mannix was leading mass protests through Melbourne.

Union leaders feature in the book in relation to party matters. But there’s no sense of the disputes taking place at the time, such as the 1903 Victorian railway strike or the 1919 seafarers’ strike.

Byrne notes that Curtin supported the concept of international socialism while defending the White Australia policy. How could Curtin reconcile these two opposing concepts? We’re not told.

The final chapter skates through the time both men spent as PM, noting Scullin’s prosecution of massive austerity during the Depression and Curtin’s adoption of conscription in World War Two.

Yet in an interview for his publisher’s blog, Byrne argues that both men, “never ceased to try to make Australia a fairer and more equal place. Their legacy, ultimately, is the era of full employment, economic growth, and expanded opportunity that they helped bring into being”.

What explains the gaps in the book and Byrne’s bizarre words of praise?

Curtin and Scullin came from competing traditions, but they were united in the belief that parliamentary politics was the only game in town. If winning elections was the way to create change, the party had to adapt to the prejudices of the majority of voters— condemning workers’ militancy and defending White Australia.

Byrne ends his book with a call for Labor to offer a genuine alternative, calling upon the spirit of Scullin and Curtin.

But from the Depression of the 1930s to the looming Depression today, the answers to the problems facing workers are not found in parliamentary manoeuvres but in workplace struggles and in the streets.

By David Glanz

Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin, By Liam Byrne, Melbourne University Press