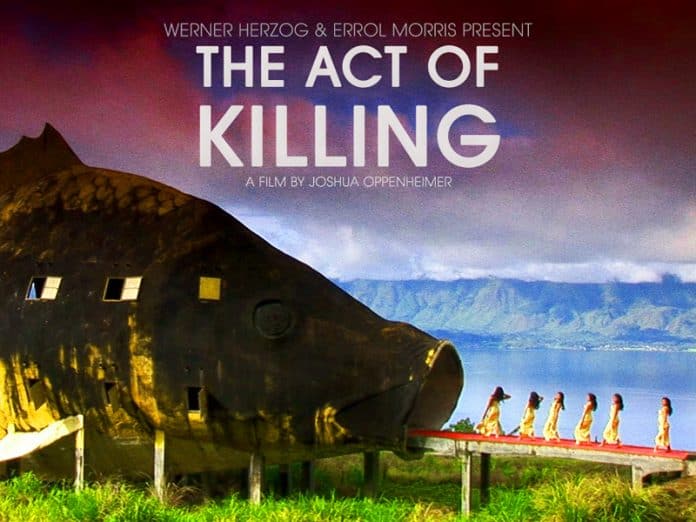

The Act of Killing

Directed by Joshua Oppenheimer

Coming soon to DVD

Today right-wing vigilantes in Indonesia can still openly boast about murdering “Communists”.

Last month the Jakarta Post reported an attack in Yogyakarta by the Indonesian Anti-Communist Front (FAKI) against relatives of victims of the 1965 anti-Communist purges.

The founder of the Yogyakarta FAKI branch declared, “[The families of the victims] are also Communists. It is legal for us to kill them, just like when we killed members of the PKI in the past.”

This is a sign of the impunity enjoyed by the killers, and of the continuing status of the anti-Communist purges even after almost 50 years.

While Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary, The Act of Killing, has not been publicly shown in Indonesian cinemas, it has reopened debate in Indonesia about the history of the Indonesian left and the tragic fate of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI).

In 1965 the PKI was widely believed to be on the threshold of power. At the time of its destruction the PKI boasted a membership of three million, the largest Communist party outside Russia and China. Membership of affiliated organisations numbered up to 20 million and the PKI’s trade union federation, SOBSI, was Indonesia’s largest.

But at the height of its strength the military, and allied civilian militias given carte-blanche for murder, slaughtered up to two million PKI members, ethnic Chinese and alleged sympathisers.

The pretext for the killings was the assassination on the night of 30 September 1965 of six army generals by the Thirtieth of September Movement, a group of disaffected junior army officers with links to the PKI. The movement’s troops took over parts of Jakarta, including national radio and announced that they intended to protect President Sukarno from a coup plot by right-wing army generals.

However they were swiftly crushed by a campaign headed by a surviving army commander, Major General Suharto. He blamed the PKI for the murders of the generals and proceeded to launch one of the bloodiest crackdowns of the 20th century.

This slaughter was the baptism of the Suharto regime (1966-98). Its chief claim to legitimacy was that it had “saved” the country from “Communist treachery” and it continued to warn of the “latent danger of the PKI” right up to its overthrow in 1998.

In the decades following the killings, anyone who criticised the Suharto dictatorship (also known as the New Order), organised in unions or advocated for social justice lived in fear of being labelled a “Communist.”

New Order propaganda lionised the army and other perpetrators as heroes and peddled myths about the bloodlust of Communists and the supposedly barbaric murder and mutilation of the generals.

The Act of Killing returns the focus to the callousness of the Communists’ persecutors.

The murderers speak

One of the murderers is the protagonist in the documentary, Anwar Congo, a gangster and member of Pancasila Youth, one of the army-sponsored paramilitary organisations that carried out the killings.

The film is remarkable for its intimate examination of the perpetrators, and their candidness in explaining their part in the bloodshed. Anwar retraces his steps in 1965 and gloats about his role as executioner, complete with graphic demonstrations of his preferred killing methods.

The film reveals important links between the killers of the Communists and Indonesia’s current ruling elite.

It shows Anwar and other killers hobnobbing with the Governor of North Sumatra, who praises them for their role in exterminating Communism. Later they are treated like celebrities on a TV talk show.

Astonishing footage shows former Vice President Jusuf Kalla grovelling to a Pancasila Youth audience, telling them, “We need gangsters to get things done.”

As the documentary descends into a surreal cinematic re-enactment of the massacres—with the killers directing—the film over-indulges the killers as they face their inner demons, with Anwar showing repentance but still insisting what he did was necessary.

But it shows little of the political context of high tensions that characterised the period under President Sukarno. Worse, this omission can portray the killings as just spontaneous slaughter, reinforcing the orientalist view of Indonesian barbarism.

Indeed, at the time many commentators downplayed the central role of the military in fomenting the violence, resorting to racist stereotypes about Indonesians, “emotionally and psychologically ready to run amok.”

But to understand the brutality of the crackdown we need to look at its roots in the tensions and dashed hopes that emerged in post-colonial Indonesia.

Independent Indonesia

Indonesian nationalist leader and first president Sukarno declared independence from the Dutch on 17 August 1945.

After four years of war, the Dutch finally recognised Indonesia’s independence in 1949. The early 1950s were a time of radical hope as the Indonesian masses emerged from fighting the Dutch, mobilised and radicalised.

As Benedict Anderson wrote, it was, “a kind of permanent round-the-clock politics in which mass organisations competed with each other at every conceivable kind of level without there being any real resolution.”

But, formal independence wasn’t all the Indonesian masses had fought and died for: Impoverished by colonialism, they expected independence should bring tangible changes to their daily lives. But by 1953, 70 per cent of estates in Java and Sumatra had returned to foreign control and unemployment remained high.

The PKI were well placed to capitalise on this resentment at the fruits of independence. In the 1955 general elections the PKI polled fourth with 16.4 per cent of the vote, and in local elections two years later in Central Java they were the most popular party.

At the same time however, the army, was also consolidating as a locus of national power for Indonesia’s emerging ruling class.

The army had always felt it deserved a political role in the affairs of the nation due to its part in the war of independence. The military’s role in Indonesian national life was strengthened with the declaration of martial law from 1957 to 1963, as regional rebellions—backed by the US—broke out in several locations across the archipelago.

Sukarno’s radical rhetoric against Dutch and US imperialism emboldened workers into occupying their foreign-owned workplaces in 1957-58, resulting in their nationalisation.

The unintended consequence was that the foreign managers were replaced by Indonesian military managers.

The army’s political role was now supplemented by a strengthened economic position. The failure of Indonesian workers to maintain control over their workplaces once they had occupied them would tragically come back to haunt them.

“Guided Democracy”, misguided strategy

Independent Indonesia was a nation in turmoil. Due to the weakness and fragmentation of the Indonesian bourgeoisie after centuries of colonialism, no coherent national agenda could be formulated.

In less than seven years six different cabinets passed through government, while secessionist movements under the influence of different sections of the elite threatened disintegration of the new nation. Sukarno became the glue that kept the state together.

Partly in response to this dysfunction, and in part due to his growing delusions of grandeur, in 1959 Sukarno introduced what he called “Guided Democracy”, dissolved parliament, suspended elections and appointed a hand picked “consultative congress.” The PKI didn’t raise any objection to this.

Sukarno, while generally supportive of the PKI, tended to position himself above partisan disputes. He mediated between the military on one side, and the Communists on the other. Meanwhile the PKI lined up uncritically behind Sukarno. For Sukarno, without any power base of his own, the PKI were an important counterweight to the army.

From 1960 the PKI increasingly placed their emphasis on Sukarno’s notion of NASAKOM (acronym of Nationalism, Religion and Communism), which would entail greater inclusion of the PKI in government.

The PKI grew rapidly over the Guided Democracy period. Its campaigns against rampant corruption, for distribution of land to the peasants, for worker involvement in the management of state enterprises, and for wage increases and price controls in a period of hyperinflation struck a chord with the Indonesian poor.

A land reform law had been introduced in 1960, but little had changed in practice. Then from 1963-1964 drought and a rat plague depleted the rice harvest, resulting in mass starvation across Java, Bali and South Sumatra. Peasants deserted their empty rice paddies and seized land elsewhere.

In rural areas from 1963 the PKI advocated “unilateral actions” against large plantations and farms to enforce the land reform law—often against Muslim landlords. (Later in 1965 the landlords would exact bloody revenge for the peasants’ audacity. Indeed conservative Muslim militias were key perpetrators of the massacres.)

From 1963-65 PKI workers seized British, American and other Western enterprises and plantations in response to the British role in the establishment of Malaysia and American meddling in Vietnam—again with the army stepping in to manage them!

In early 1965, Sukarno and the PKI began advocating the formation of a Fifth Armed Force—arming workers and peasants—to rival the military’s monopoly on arms. Rumours about a shipment of arms from China circulated.

Then in August 1965 Sukarno’s health took a turn for the worse, triggering speculation on who would succeed him. In the months leading up to September 30 the masses mobilised in increasing numbers for price controls and land distribution. Events were swiftly heading towards a showdown with the army and landlord class.

Bloodbath

In these volatile conditions it only took a spark to set off a raging inferno. The botched coup provided it. Few bloodbaths in history can rival that which befell the Indonesian Communist Party from 1965-66.

Time magazine witnessed this horrific scene in late 1966:

“The murder campaign became so brazen in parts of rural East Java that Moslem [sic] bands placed the heads of victims on poles and paraded them through villages. The killings have been on such a scale that the disposal of the corpses has created a serious sanitation problem in East Java and Northern Sumatra where the humid air bears the reek of decaying flesh. Travellers from those areas tell of small rivers and streams that have been literally clogged with bodies.”

The bulk of Indonesia’s most militant unionists and activists were murdered, along with virtually the entire leadership of the PKI.

PKI leaders offered no guidance to their millions of members on how to resist the slaughter. They had so utterly subordinated themselves to Sukarno that when the army removed him, the PKI was defenceless.

Dictatorship

Suharto seized complete control and by March 1966 had consolidated his dictatorial power.

The ruling classes of the West delighted in this extermination of the Communist threat. Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt remarked casually at the time that, “With 500,000 to 1 million Communist sympathisers knocked off, I think it is safe to assume a reorientation has taken place.”

The US actively encouraged complete annihilation of the PKI in order to ensure that “reorientation” was absolute.

They weren’t disappointed. The killings aimed to break completely the organisation and morale of the masses. Under the “New Order” that followed the masses were denied any political participation, as any degree of politicisation of the people was deemed dangerous.

Lessons

How did it go so terribly wrong? Crucially, the PKI’s aim wasn’t the masses taking power by their own efforts and with their own institutions of grassroots democracy, but rather taking a greater share of power within the Indonesian capitalist state.

According to PKI Chairman Aidit, the state was of a dual nature, with a “pro-people” aspect and an “anti-people” aspect. The PKI followed Sukarno in calling for a “retooling” of the state apparatus to tilt the balance in favour of the “pro-people” elements. In effect, this resulted in the complete subordination of class struggle to maintaining an alliance with Sukarno.

Only after the catastrophe of 1965 did the remnants of the PKI see the error of this “two aspect theory” of the state. In 1966 they wrote: “According to this ‘two-aspect theory’ a miracle could happen in Indonesia. Namely the state could cease to be an instrument of the ruling oppressor classes to subjugate other classes, but could be made the instrument shared by both the oppressor classes and the oppressed classes. And the fundamental change in state power … could be peacefully accomplished by developing the ‘pro-people’ aspect and gradually liquidating the ‘anti-people’ aspect.”

Alas, this correction of their “top-down” approach came too late.

This muddled analysis stemmed from the PKI’s embrace of the Stalinist two-stage theory of revolution which dictated that the coming revolution could not go beyond the bourgeois-democratic stage, and that a socialist revolution was not possible in the immediate future.

This meant that the PKI viewed the aim of the revolution as bringing the national bourgeoisie to power.

Aidit spelled this out: “The revolutionary forces in Indonesia are composed of all classes and groups suffering from imperialist and feudal oppression. They are the proletariat (the working class), the peasants, the petty bourgeoisie, the national bourgeoisie and other democrats. They must be united in an anti-imperialist and anti-feudal national united front based on the worker-peasant alliance and led by the working class.”

Despite lip service to working class leadership, holding together a coalition with the “national bourgeoisie” came at the expense of worker and peasant demands like workers’ control of the factories and land reform which would harm its better off “allies.” This meant holding back the only force that could build socialism: the working class leading the peasant masses.

Academic Rex Mortimer described a PKI report to a party congress where, “The entire emphasis … was on the self-abnegating role of the workers and their political responsibilities toward other classes and the nation as a whole”.

They identified Sukarno as the embodiment of this “national bourgeoisie”. So when the counter-revolution swung into full force, and Sukarno was unable to stem the slaughter, their mass membership was disarmed. The PKI made no attempt to organise strikes or demonstrations to resist the crackdown.

The Act of Killing reveals the challenges that the current generation of Indonesian activists face in overcoming the defeat of 1965. Pancasila Youth, the militia Anwar was a member of during the killings, still harasses Indonesian workers’ demonstrations today, with the backing of employers and the authorities. In fact, scores of striking workers were severely injured in clashes with Pancasila Youth during the Indonesian national strike this month.

Adi, another of the perpetrators in the film, responded to inquiries about the morality of his acts with these words: “War crimes are defined by the winners. I’m a winner. So I can make my own definitions.”

This film creates space to reveal the bloody history of Indonesia’s ruling class and the way anti-Communism has been used to sustain their rule. It can also give a boost to current activists’ understanding of the PKI’s failed strategy of capturing state power.

With the Indonesia workers’ movement again on the rise, the struggle for a genuine socialism-from-below is back on the agenda.

By Lachlan Marshall

Further reading:

John Roosa, Pretext for Mass Murder

Rex Mortimer, Indonesian Communism under Sukarno