In this 50th anniversary of the Whitlam Labor government (1972-75), social democrats, feminists and socialist reformists are not only celebrating but also raising new hopes of meaningful change from the Labor government led by Anthony Albanese.

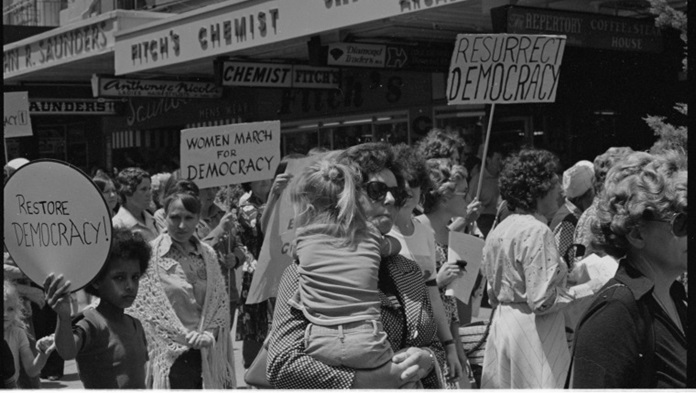

A recently-published book, Women and Whitlam: Revisiting the Revolution, edited by historian Michelle Arrow, makes strong arguments for feminist hope. However, the book shows that such governments are no guarantee of liberatory change—what a state concedes, a state can take back. The book is an argument for a new women’s movement.

Arrow’s introduction cautiously begins with the sacking of Whitlam, reminding readers of the powerful enemies of women’s rights represented by the Liberal Party. The foreword by Tanya Plibersek reminds us that a social democratic government can legislate meaningful reforms but ongoing feminist vigilance is essential.

As a key leader of the ALP, she should know. She has been a Deputy Leader and Minister for the Status of Women and is currently the Minister for the Environment and Water approving polluting coal mines.

There are chapters from 22 other contributors, mostly women who were active in the seventies and also younger people active today. They remind us that the Whitlam government did more to improve women’s status than any other federal government before or since.

The ground-breaking achievements were achieved on the back of a rising women’s movement alongside a tremendous period of union militancy. Whitlam’s reforms reflected that mobilisation from below.

The reforms included equal pay for work of equal value, the Medibank public health insurance scheme, free tertiary education, supporting mothers’ benefit, and easier divorce and the family law court. But most of these have been eradicated or limited by later Liberal and Labor governments.

The book is divided into five parts covering the various issues of the time, with two to four contributors commenting briefly in each part, showing the rich history of these few years. Some of the writers are liberal feminists who had the ear of this government at the time.

I don’t have space to address each section. Part One, “Women and political influence”, is introduced by political scientist Marian Sawer and covers the uneven relationship between the government and sections of the women’s movement, particularly the Women’s Electoral Lobby and the Women’s Liberation Movement.

Part Two, “Women and the law”, covers human rights and the Family Law Act and is introduced by Kim Rubenstein; it traces the important role of the progressive Family Court which was eventually destroyed by the Howard government.

Karen Soldatic introduces Part Three, “Health and social policy”, which includes the introduction of the Supporting Mothers Benefit, not always defended by Labor. Terese Edwards (CEO of the National Council for Single Mothers and their Children) reminds the reader that, as Labor Prime Minister, Julia Gillard extended John Howard’s cuts to parenting payments, which drove many single mothers further into poverty.

Part Four, “Media, arts and education”, introduced by Julie McLeod, covers how culture generally was more sexist at this time and was challenged by artists and others who benefited partly from the government’s financial support, unusual in Australia.

Demolish all oppression

The most relevant for us today is Part Five, “Legacies: What remains to be done?”, which is introduced by Heidi Norman. Blair Williams describes today’s gender issues of sexual harassment and domestic violence. She argues strongly for a new movement which seeks an intersectional approach, “to demolish all hierarchies of oppression, from patriarchy, capitalism, white supremacy and ableism to cisheteronormativity”.

Ranuka Tandan presents a radical critique of the liberal feminism of the Whitlam era and argues for dismantling “patriarchal structures like the police and the State”. She recognises the class divisions among women and the need for union struggle and she poses alternatives, like new strategies of abolitionist socialist feminism, grass roots organising, industrial campaigns and learning from Indigenous campaigns against the colonial state.

I agree we need to go beyond liberal feminism and outside parliament—if we are going to win the fight against oppression we must build a movement that challenges the state and develops the confidence to withdraw our labour in industrial action because that’s where our power lies.

For Tandan, the 1970s illustrated a problem with joining male-dominated unions which, she argues, limited outcomes of the fight for equal pay. However, she omits the role of women as union militants in the 1970s and downplays the major role of leftwing women and men workers and students, who, together, challenged sexism in unions, albeit unevenly.

The Whitlam government won the election on the back of a working class revolt. Feminism, always an element in the background of liberal reform politics, was thrust onto the political agenda by the various actions led by many radical women, which included fights for abortion rights and equal pay.

Whitlam’s agenda benefitted feminist struggles, but he also benefitted from the audience/supporters feminists brought him, allowing him to argue for a modernising state which offered a class harmony and social stability at little cost in the midst of crisis to the bosses.

Most Australian women made substantial steps toward equality, particularly white middle class women. However, the three years 1972-75 did not become a revolution. In Part Three, Sara Dowse, who was head of the women’s unit in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet at this time, reports that by 1975 many welfare benefits were being destroyed by that same government.

Today, a new social movement cannot rely on Labor to keep what few promises it makes. Time and again Labor delivers legislative processes that concede minor improvements but which leave fundamental structures in place.

For example, by not tackling gender-segregated industries and not supporting significant pay rises in feminised industries, the Albanese Labor Party leaves intact the structures which support inequality.

In 2019, a Labor campaign promised, if elected, to make federal health funding for hospitals dependent on providing all reproductive health services (that is, including abortion). However, Albanese has left in place a very inequitable and discriminatory healthcare system, whereby in most states publicly-funded Catholic-run hospitals can veto procedures like abortion.

Labor’s political limitations are not one-off flaws but systematic and a result of the Labor project to support the profitability of Australian capitalism. The experience of all Labor governments has demonstrated the impossibility of achieving class harmony in support of a capitalist national interest.

Labor’s vision for Australia will not solve the myriad problems revealed by multiple crises including the cost of living and catastrophic climate change. We live in a brutal world being held together by often authoritarian responses that also involve extreme sexism, racism, homophobia and transphobia. Labor champions a racist nationalism and defends the militarisation of the Australian state.

The demands of the working class, First Nations people and refugees for a better life are so necessary but are met by the likes of Albanese and Plibersek turning their backs.

This book includes interesting and useful historical information and the radical hopes, ideas and achievements of the period should be celebrated. To finally realise those hopes we need to look to uniting social movement and union action from below. Women’s and LGBTIQ rights will not be a priority, nor workers’ rights, unless we fight for them.

By Judy McVey

Women and Whitlam: Revisiting the Revolution

Arrow, M. (2023) (Ed.)

NewSouth Publishing