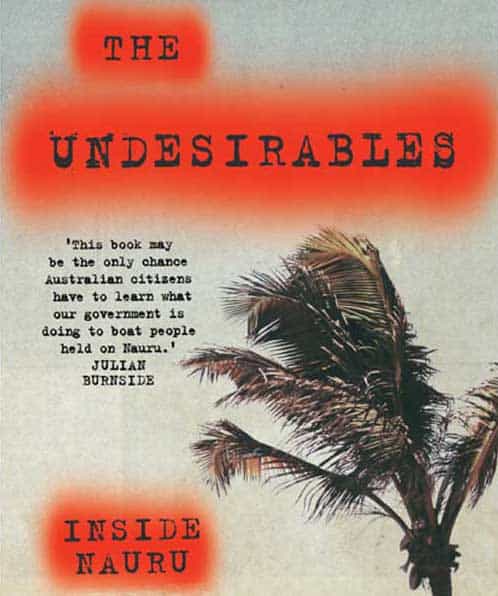

Mark Isaacs spent almost a year as a Salvation Army worker on Nauru. The Undesirables is his compelling firsthand account of the horror, injustice and disaster of offshore detention.

It vividly exposes Nauru’s detention centre as a factory for mental illness, where asylum seekers are driven insane by uncertainty and cruelty. After expressing shock at one attempted suicide, Isaacs describes how, “A Wilson guard informed us that Christmas Island had two attempted suicides a day. That’s what we had to expect. We were working in death factories.” In a horrifying case, one man on Nauru is driven to a psychotic episode, acting like a dog and grunting in the dirt.

Band aids

Through his own experience as a Salvation Army worker, Isaacs became increasingly critical of the idea that the Salvos or welfare groups can help asylum seekers within the confines of carrying out government policy. Isaacs draws the conclusion that the Salvos contract is “a band aid on a bullet wound”.

Isaacs fought hard for recreational activities for the men on Nauru. But despite his good intentions, no Nauruan Premier League or Mr Nauru Cricket Cup could address why asylum seekers had fled their families and homes—the desperate need for guaranteed protection and safety. As one asylum seeker pointed out when the media picked up images of the asylum seekers playing games, “We may laugh but we are crying inside”.

The efforts of Isaacs and other Salvos to improve conditions were constantly frustrated. The cruelty is deliberate. The government has created internment camps in an attempt to make life worse than the conditions asylum seekers are fleeing.

One of the asylum seekers, Pehzman, expresses his frustration at having to line up twice a day for one hour in the heat and sun to get medication:

“The Wilson Guard offered a patronising barb into the tense silence. ‘Just calm down, LIC029’.

“‘He has a name,’ I interjected.

“The guard put his face up to mine and whispered, ‘When we go in there they are numbers. That is all.’”

The asylum seekers live on a knife edge, waiting for visits from former Labor Immigration Minister Chris Bowen or any action from the Immigration Department on processing their asylum claims. They have the power to immediately let the asylum seekers into the community and guarantee protection. Isaacs reports that before Bowen’s visit, “In the days prior to his arrival it was all the men could speak of. They placed their hope in his hands. Chris Bowen came to Nauru, he performed a swift examination of the camp, and then he left.”

Neo-colony

The “pressure cooker” of tension led to riots on Nauru. Property damage was the most widely reported aspect in the media. Isaacs coordinated a response from Salvation Army staff, a letter that revealed the underlying mental anguish of asylum seekers that led to the riots, along with horrific accounts of coordinated self-harm and attempted suicide.

The Nauruan reaction to the riots also revealed the problems created by Australia imposing the detention centre on Nauru. Australia still sees Nauru as its neo-colonial playground. Until independence in 1968 Australia oversaw strip-mining of over 80 per cent of Nauruan land, paying a pittance back to Nauru in royalties. Isaacs even heard that the Nauruan President was leasing his house to Australian officials.

There was no public consultation about the introduction of asylum seekers to their island. The detention centre is continuing Australia’s environmental destruction of Nauru, with phenomenal use of plastic water bottles and other waste.

One incident on an excursion reveals the deliberate creation of a divide between asylum seekers and Nauruans. An asylum seeker who dared to try walking towards a Nauruan was stopped by a Wilson security guard: “The guard pointed over Fayiz’s shoulder and said, ‘You are an asylum seeker. You do not speak to Nauruans’.” Isaacs tried to organise programs to help integrate Nauruans and asylum seekers, but nobody would implement them.

In July 2013, the Nauruan government reacted to the riot of asylum seekers by mobilising a section of the community into an emergency police force. A group of Nauruans were waiting outside the camp with weapons, including machetes. Many of the asylum seekers were seriously injured during the riot. Many were beaten in jail and denied food for four days. The detention centre was fittingly burnt to the ground by the asylum seekers.

Isaacs uses his own conversations with refugees on Nauru to debunk many of the anti-refugee myths, from the “people smugglers’ business model” supposedly being the reason people take boat journeys, to the idea most asylum seekers are economic migrants. The Undesirables is a valuable tool in the fight against Australia’s brutal border regime.

By Feiyi Zhang

The Undesirables: Inside Nauru

By Mark Isaacs

Hardie Grant Books, $29.95