By Judy McVey

Introduction

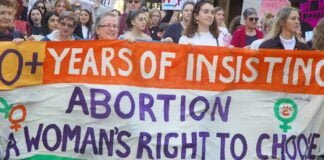

Around the world, from Washington to Warsaw, Italy to Ireland, and in Sydney, women have been protesting against sexual harassment and for abortion rights, for control over their own bodies. The NSW parliament finally voted for ‘decriminalisation’ of abortion in September 2019, to remove it from the Crimes Act of 1900, joining most other states and territories.

In the last 25 years, Australia has been part of an international trend toward abortion law liberalisation; around 60 countries now enjoy access at least to early abortions (in the first 12 weeks). Ireland, a country once stereotyped as insular and socially conservative, now has more progressive abortion laws than most other jurisdictions. In a huge turnout for a referendum in 2018, a majority voted Yes to abortion. As Together for Yes convenor Gráinne Griffin put it, Ireland’s victory “has lit a beacon of hope for countries all over the world.” Chile introduced some reforms in 2017. Decriminalisation is on the agenda in New Zealand and Argentina.

Since abortion was decriminalised in most Australian jurisdictions, healthcare providers are allowed to deliver these services without uncertainty and fear of criminal proceedings. NSW obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Roach said: “It isn’t just words or the possibility of being charged, it’s the stigma that’s associated with making abortion the one area of healthcare that is in the Crimes Act. Therefore removing it sends a significant message that abortion is the right of a woman and that it is part of healthcare.”[i]

However, we still have not achieved safe, legal abortion on demand. Abortion should be a personal decision of the woman involved; but it remains a political question under the control of the state (within a doctor-patient relationship).

Even though most Australian states have ‘decriminalised’ abortion, it,

“is the subject of criminal law in all Australian states and territories, except the Australian Capital Territory. Each state/territory has legislation prohibiting unlawful abortion.”[ii] It is not the woman who has the right to decide on abortion in every circumstance, despite opinion polls indicating more than 80 per cent, including 77 per cent of those who identify as religious, support a woman’s right to choose.[iii] Only “approximately 4 per cent… are opposed to abortion in every circumstance.”[iv]

For most women, abortion is accessible in Australia. It is reliably estimated (there are no national statistics) that 70-80,000 lawful abortions will be performed annually. But for many it remains a difficult journey, exacerbated by the role of anti-abortion forces.

The Catholic Church and the Right like to portray the abortion issue as a matter of being ‘pro-life’ (rather than anti-abortion) versus ‘pro-abortion’ (rather than pro-choice), based on politics which state abortion is about the ‘murder’ of an unborn human being, the foetus. Capitalist law has never recognised the foetus as a person. Right to Life (RTL) groups among others have never recognised the actual superior legal rights of the women on whom a foetus is totally dependent until born. Such simplistic labelling betrays the significance of the need for safe and legal access to abortion.

Most surgical abortions involve a simple and safe medical procedure, less dangerous than pregnancy and childbirth if performed by trained staff; and RU486 or mifepristone, the abortion pill (effective up to nine weeks), is even more straightforward. Outlawing it does not stop women seeking abortions for unwanted pregnancies, but it forces many to obtain potentially fatal terminations from backyard operators, as explained by the World Health Organisation (WHO).[v]

As 41 per cent of women of childbearing age worldwide live under restrictive laws, 23,000 will die each year from complications of unsafe abortions(approximately 8 per cent of maternal deaths).[vi]

While internationally 59 per cent enjoy improved conditions and access to contraception and abortion, we’re not there yet. For all women, after the century-long struggle, the light at the end of the tunnel is murky.

In the 21st century there is a new threat to the gains in the US and Europe. Anti-abortion campaigners have successfully turned back the clock in many states of the US. As of 1 September 2019, 29 states were considered hostile toward abortion rights, 14 states were considered supportive and seven states were somewhere in between.[vii] The US has a major influence on reproductive health in developing countries; the Trump government has strengthened the ‘global gag’ order on funding services, which denies US federal funding to any international aid bodies who advise on abortion services (see below).

Yet, resistance is on the agenda: the 2016 strike by 150,000 Polish women stopped the government’s attempt to ban all abortion there, inspiring the ‘Women’s Marches’ that filled the streets of the US and across the world on Donald Trump’s first day as President in January 2017. Huge protests in 2019 opposed the Indonesian government considering heavier criminal penalties for abortion.

This pamphlet mostly refers to ‘women’ for simplicity but it acknowledges all those who experience pregnancy and abortion. It is important to recognise that trans men, non-binary people and others who do not identify as women may need to access reproductive health services.

Class, sexuality, (dis) ability and race affect the provision of reproductive services, and access depends on ethnic background, geography, age and income. Aboriginal women suffered involuntary abortion and sterilisation until fairly recently. Forced sterilisation of people with disability, as well as people with intersex variations, is an ongoing practice that remains legal and sanctioned by governments in Australia.[viii] Young women under 16 should not require parental consent.

As the Public Health Association of Australia argues: “Abortion should be regulated in the same way as other health procedures, without additional barriers or conditions. Regulation of abortion should be removed from Australian criminal law. States and territories should actively work toward equitable access (including geographic and financial access) to abortion services, with a mix of public and private services available.”[ix] An abortion is costly; for example, it can cost $460 in NSW and $795 in WA. Cost depends on type of service and length of pregnancy, rising beyond $3000 for late-term surgical abortions. Medicare covers just one fifth of the cost in some cases. As a basic human right such reproductive health services should be free.

These issues illustrate the contradictory situation for women under late capitalism, where women more and more are accepted formally as equals, in international and local laws, but at the same time, the structures of capitalism and the demands of the profit motive put economic and political barriers in the way of liberation.

The ALP Platform states support for improvement in “accessibility, legality and affordability of surgical and medical terminations across Australia, including decriminalisation in all States and Territories and the provision of abortion in public hospitals” among other aspects of pro-choice services.[x] Unfortunately, politicians often make totally unnecessary concessions in an effort to strike compromises inside parliament. The parliamentary and legal debates undoubtedly represent elite political opinion, which reflects the needs of capitalism. National opinion polls, although not fully reliable, better represent the attitudes of the mass of the population (see above).

A return to the days of unsafe, illegal back street abortion seems unlikely in Australia while there is mass support for women’s right to choose. Yet with women’s participation in society and the workforce at unprecedented levels, why is control of women’s fertility still not theirs?

Abortion in Australian – the law and practice

Abortion in Australia is more easily available than in most countries; however, the laws are complex and access still has numerous unnecessary restrictions. In the ACT, abortion was removed from the criminal code in 2002, showing that abortion can be regulated under the health regulations, like other simple health procedures, and available at the request of the woman concerned. Yet other Australian states and territories have not followed suit (see Table 1).

Four states (Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania and NSW) allow abortion on request for early abortions, based on arbitrary time limits. Outside these time limits, two medical practitioners (in NSW they must be ‘specialists’; in Tasmania one must be a gynecologist/obstetrician) are required to assess whether the abortion is legally permissible—in Victoria after 24 weeks, Queensland and NSW after 22 weeks, Tasmania after 16 weeks. In the Northern Territory (NT) early abortions until 14 weeks are allowed outside criminal law if a doctor approves.

They have decriminalised these procedures, yet criminal law covers certain other procedures—and persons who are not registered medical practitioners are liable for imprisonment if they conduct an abortion or assist. Women are not liable for unlawful abortion. While more than 98 per cent of abortions take place within 20 weeks’ gestation, and approximately 96 per cent within 12 weeks, late-term abortion remains necessary for a variety of reasons (see below).

Thus, the state delegates doctors as the gatekeepers determining whether some abortions are permissible. While women are responsible for childbearing and rearing, doctors have the right to decide. While abortion is a simple procedure only doctors can be trained to perform surgical abortions.

In Western Australia and South Australia, criminal law remains critical to whether the procedure is considered ‘lawful’. In WA an abortion is unlawful, and a practitioner criminally liable, unless ‘justified’ according to criteria laid down in section 334 of the Health Act. There is a 20-week limit (unless two doctors, chosen from a panel of six appointed by the Minister, agree that the late term abortion is ‘justified’). Further, an ‘informed consent’ clause requires that a doctor, other than the one who performs the abortion, has provided counselling about the risks of abortion. Young women under 16 must involve the custodial parent in consultations.

In SA, abortion must be legally authorised under the criminal law, and is permitted up to 28 weeks if required because of the physical or mental health of the woman or deformity of the foetus. The operation must usually be performed in a hospital. In SA, women are potentially still liable for a prison sentence (the maximum is life). The SA government is considering decriminalisation currently.

All these restrictive laws should be repealed and replaced with the ACT model. So long as the process is one of tinkering with such legislation, further restrictions can be imposed. This has been part of the anti-abortion strategy. Recognising that time is critical to safe terminations, anti-abortion politicians have proposed extra tasks like compulsory counselling which slow down the approval process. Clauses relating to doctors’ right to conscientious objection have the effect of undermining women or making them feel guilty, even though the doctor is required to refer patients to a willing practitioner, or in NSW, approved health department information.

Keeping abortion legal and under health system regulation is essential for access to safe abortion procedures, but it is not sufficient; decriminalisation, per se, has not led to wider access for women. Tasmania has no clinic providing abortion services and women must travel to the mainland, incurring additional travel costs. Hospitals run by the Catholic Church refuse abortion.

Accessibility and availability of quality abortion services is essential, especially for women threatened with domestic violence. Regional areas are poorly serviced. While the availability of medical abortion (RU486) has increased women’s choices, there remain unnecessary restrictions of usually requiring multiple appointments with (and travel to) a GP. Since 2015 early medical abortion can be provided via telemedicine. In SA and, until 2019 in the ACT, the proviso that all abortions, including medical abortion, must be carried out in approved premises meant this cheaper and simpler activity was compromised.[xi]

As new technology provides more accessible healthcare, the specific restrictions on this particular health procedure often limits technology’s effectiveness and can impose unnecessary delay and stress, rather than improve access. For example, because interpreters are not provided, those who cannot understand and speak English may not have access to telemedicine.

Journalist Judith Ireland reports: “Access to abortion is also hampered by a lack of training for doctors and nurses. About 1500 of Australia’s 35,000 GPs are registered to prescribe a medical termination … Marie Stopes, a national not-for-profit abortion and contraception provider, says there is a ‘dearth in the workforce … [which] ultimately limits abortion provision now and into the future’… The not-for-profit organisation provides free and low-cost services to women who cannot afford to have an abortion at a private clinic, where it can cost hundreds of dollars.”[xii]

The state plays an inconsistent role in determining the practice of abortion provision. The federal government is responsible for population policy, funding public hospitals, pharmaceuticals and controlling Medicare and private health fund regulations; although birth control lies with the states and territories. Practical improvements are possible. Before the 2019 federal election the Labor Party promised that, if elected, the Commonwealth-state hospital funding agreements would “expect termination services to be provided consistently in public hospitals”. Only between 0 and 10 per cent of surgical abortions are performed in the public hospital system; in Queensland, it’s just 1 per cent.

As The Greens argue: “Eliminating out-of-pocket costs and expanding equal access through the public hospital system is the best way to make sure all women are able to exercise their fundamental right to control their own bodies and their own health.”[xiii] We need free universal quality healthcare, Australia-wide. Everyone should have real choice whether to give birth or not; real choice on free, safe, reliable and appropriate contraception and free (or at least affordable), safe, accessible abortion on demand. Australia does not promise this basic right. And neither does it promise all women affordable voluntary safe childbirth and the raising of children.

The underlying experience for most Australian women is that, despite the fact one in four women will have an abortion, it remains taboo and few women speak publicly about it, especially in rural areas. Doctors are wary of the stigma of being the “only abortionist in town”, even if they support abortion provision. As one woman said: “We either need doctors who will perform a medical abortion or refer on for help elsewhere. But in somewhere like Swan Hill [Vic], which is fairly conservative, it’s the most taboo topic ever.”[xiv]

How a society treats its most disadvantaged is a measure of the human rights of a society: reproductive health is crucial for all of us. According to Health & Human Rights Journal, between 2008-12, two out of 100,000 females who gave birth in Australia died. For Aboriginal women, it was seven times that. In that period, none died from abortion, but that was not always the case.[xv]

Abortion and capitalism

Abortion became a serious criminal offence only with the development of capitalism. Most human societies have attempted to control their fertility rates. Literary evidence indicates the widespread practice of abortion in ancient Greece, carried out by skilled female midwives, and in Asian countries. Historians detail numerous methods of birth control used by peasant women in 16th and 17th century feudal Europe, ranging from moulded discs of beeswax fitted over the cervix to spermicides made from lemon juice. Only in the 20th century, with the development of antiseptics and anaesthetics, did abortion become an extremely safe and reliable procedure, in the hands of trained practitioners.

While today abortion is banned by the church from conception, until 1869 the Catholic Church did not absolutely condemn terminations. Following Aristotle’s definition, the church deemed life began when the soul entered the foetus—40 days for males and 80 days for females. In non-Catholic English feudal society, human life was thought to begin when the foetus moved—at ‘quickening’—about three to four months (around 100 days) into the pregnancy. Only the mother could accurately judge when the first movement was felt, and the church and state effectively ignored abortion until the 1800s.

The English common law during this time stated abortion was a misdemeanour only if it could be proven there was a ‘quickening’. This definition was retained in the first statutes to deal with abortion, initiated in 1803 in Britain, but disappeared when the law was refined and consolidated into the 1861 Offences Against the Person Act. This outlawed abortion at any stage of pregnancy; it became the model for the Australian colonies.

To understand why, we need to examine the development of the capitalist family, which became the site responsible for privatised reproduction of labour. In feudal society the patriarchal peasant family had been the main unit of production. Under capitalism, men usually went to workplaces outside the home. For the rising capitalist ruling class and middle class, women remained at home, ornaments and homemakers. Their family consisted of a male breadwinner, and a housebound female who held responsibility for rearing children, while at the same time custody of children was the father’s legal right. The mother had no social or political rights, not even over her own body.

During the industrial revolution, poor peasants were driven off their land and drawn into the new factories, mines and mills. The family was no longer a productive unit, with family members working jobs as individuals outside the home. Often women and children were the preferred employees because they accepted lower wages. Women worked long hours in horrendous conditions, with no time off even for childbirth. Infant mortality skyrocketed. Abortion became a booming, although illegal, business as women tried to limit pregnancies to keep their jobs. The unmarried often had to ‘farm out’ their own babies in order to secure a position as a wet-nurse, feeding the babies of the rich. The alternative was worse poverty in unemployment, homelessness or the dreaded workhouse.

In these conditions of misery and degradation, the new working class was nearly incapable of reproducing itself. Friedrich Engels’ Condition of the Working-Class in England details the extent of child and female labour along with the poverty, industrial accidents and disease in industrial cities like Manchester. “Of 419,560 factory operatives in the British Empire in 1839 … 242,296 [were] female … of whom 112,192 were less than eighteen years old.” Almost half of male workers were under 18. In cotton, wool and flax mills, women were over half the workforce. “[M]ore than 57 per cent of the children of the working-class perish before the fifth year… epidemics in Manchester and Liverpool are three times more fatal than in country districts…”

The demand for a working-class family supported by a ‘family wage’ paid to the male workers, allowing women to raise children safely at home, became popular within the working class. The more far-sighted sections of the capitalist class also looked to this family structure as a means to ensure the reproduction of the next generation of workers, as new industries developed which required more skilled, healthier and educated workers. Universal education, protective industrial legislation to regulate working conditions for women and children and health laws were also a feature of this period. Similar moves to establish the nuclear family as a cornerstone of social organisation took place across the western world, including in Australia.

Along with attempts to ameliorate some of the worst aspects of working class life went an ideological campaign to convince men and women of their particular social roles, as husband/breadwinner and wife/mother, within this nuclear family. The late 19th century witnessed a barrage of pro-family campaigns and legislation aimed at shaping the working class family into a mechanism to churn out socialised and disciplined factory fodder.

The 1861 abortion legislation was part of a raft of laws regulating sexuality and ‘vice’. Male homosexuality was outlawed, divorce made almost impossible and so-called illegitimate children were discouraged through discrimination and the barbaric treatment of single mothers. In colonial Australia social reformers from Governor Macquarie’s time onwards campaigned for an ideal family model. Caroline Chisholm famously emphasised the role of women (‘God’s Police’) in ‘civilising’ Australian society, whose convict origins threatened social dislocation. Conservative ideology surrounding the family was a key component of social control, as Henry Parkes told the NSW parliament: “Our business being to colonise the country, there was only one way to do it—by spreading over it all the associations and connections of family life.”

Since many women and men opposed this, Chisholm understood that more than argument would be required to dragoon women into housewifery. She recommended that, “the rate payable for female labour should be proportional on a lower scale than that paid to the men… higher wages tempt many girls to keep single while it encourages indolent and lazy men to depend more and more upon their wives’ industry than upon their own exertions thus partly reversing the design of nature.” Men were hit with ideological messages, according to Anne Summers: “The taming and domestication of the self-professed independent man became a standard theme in late nineteenth century fiction, especially that written by women.”

Partly through these efforts, the family and marriage were established by the early years of the 20th century: “Of those men aged between 25 and 29 in 1871, 24 per cent had never married; by 1901 this had dropped to 20 per cent and ten years later it was 15 per cent.” Australian governments proceeded with a mass of puritanical legislation, such as the age of consent laws, outlawing of brothels, and the suppression of advertising of contraceptives, abortifacients and birth control information.

The western nuclear family became a social institution surrounded by ideological propositions—described as the ‘traditional’ nuclear family, a ‘natural form of human organisation’ as if it had always existed, universally. Child bearing and rearing became the only really natural role for women. Ideology was reinforced by state welfare targeted to assist with costs of children; although under the White Australia policy only white women were entitled. In particular, Indigenous families were disempowered, as Indigenous activist Bobbi Sykes explained, and “community survival was threatened” in the context of coerced abortions, sterilisations and child removal.

The defining feature of the nuclear family in the working class is its social role—providing support and care for workers and their children, in particular the reproduction of the working class, at little cost to the system. However, far from being ‘natural’, the family and these roles were created to meet the capitalist need to reproduce a skilled workforce on the cheap. Western capitalism relies heavily on the family for cheap privatised care—not just for children, but also for unemployed, aged and sick family members.

For the bourgeoisie, at least three further advantages flow from the working class family. First, the conservative pro-family ideology bolsters support for the ‘naturalness’ of capitalism itself and helps maintain stability for the system. Second, because women’s role in the family involves unpaid work and the assumption that women have other means of support, all work by women is devalued—hence their lower wages in the paid workforce, further cheapening production costs. Third, this enables the bosses to undermine men’s wages. When workers are threatened with unemployment because others work more cheaply, they accept lower wages themselves. Overall, the bosses; hold over workers is strengthened because of the gender divide.

The reality of family life is far from the ideal painted, and the so-called family wage has never provided adequate security, as shown by how often women have had to work outside the home. Yet working people supported the family as a defence organisation for the working class, providing an element of control over at least one aspect of their otherwise almost powerless lives. Today the social role of the family remains largely intact, although many people resist the strict formal organisation and opt for alternative lifestyles.

The most important role of anti-abortion legislation is to reinforce the ideology of the family—it helps remind women of their primary social role. When abortion is ‘unlawful’ it is deemed a crime against the family and against women’s ‘natural’ role as mother and homemaker. Concealed behind the debates over the legal rights of foetus versus woman lies the crucial issue of unpaid labour in the home.

The family’s changing fortunes

Abortion laws have long reflected the fortunes of the nuclear family. The enormous changes in family life since the 1960s have been accompanied by the liberalisation of abortion law. Both were associated with the growth of the female workforce.

The 1960s economic boom increased the demand for female labour, which in turn fostered confidence among women workers and a willingness to fight. In Australia, workforce participation by married women rose from 8.6 per cent in 1947 to 18.7 per cent in 1961, then to 32.7 per cent at the time of the 1971 census.[xvi] More women continued their education beyond secondary school. They faced a contradiction: while society encouraged them to work and study, it also said they could not do this on an equal basis with men.

Pro-family ideology had flourished in the 1950s, partly due to the government’s xenophobic ‘Populate or Perish’ strategy to increase the population as protection from invasion by ‘Asian hordes’. Women faced numerous restrictions: they had to leave work in the public service and armed forces once married; they earned less than men, as low as 50 – 75 per cent; home-based childcare was the norm; divorce was extremely difficult; rape and domestic violence within marriage were legal; contraception was legally prohibited and highly taxed; and abortion illegal. Unmarried single mothers were not entitled to a government allowance.

From 1969 the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) grew out of these contradictions. By the late 1960s a different political context had emerged with a series of new social movements—against the war in Vietnam, for Aboriginal rights and against the racism in South Africa and the USA, for student rights, union rights, higher wages for workers and environmental reform. The catalyst for these struggles was rising expectations hitting against a wall of ideological conservatism. This potential for change and the development of the contraceptive pill ushered in new ideas that sexuality was not just about procreation—greater acceptance of homosexuality, de facto marriage, divorce, single parents and so-called illegitimate children. These ideas both reflected and encouraged changing attitudes to women and their role in the family. Superficially it appears that there was an enormous undermining of conservative ideas about sexuality and the family.

Today more than half the adult female population works outside the home (up from around one third in 1966), representing 47 per cent of the workforce (up from less than 28 per cent in 1979). Women constitute 37 per cent of all full-time employees and 68.5 per cent of all part-time employees.[xvii]

Over the past century women have reduced the size of families—since 1976 the Australian total fertility rate (TFR) has always been below the replacement level of 2.1; by 2017 it had fallen to 1.74 babies per woman. Women give birth later in life. Silvia Yass writes that according to the ABS: “24 per cent of Australian women will never have children, and child-free homes will overtake the number of households with children by 2031.”[xviii]

However, it is important to define the nuclear family by its role in childbearing and rearing, not by a mechanical formula of male plus female plus two kids. The total number of families (including married and de facto couples) in 2016 was 6,070,316—44.7 per cent of these were couple families with children, 37.8 per cent were couple families without children and 15.8 per cent were one-parent families (of which 81.8 per cent were headed by a woman).[xix] This is just as true of homosexual couples who are either adopting children or using IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) treatments, as it is of heterosexual couples.

Despite ideological challenges, the nuclear family structure is alive and well. What all the models have in common is privatised care for children and non-working family members, with the mother almost always shouldering the greatest burden. In the neo-liberal era, government cutbacks and privatisation of services make this burden enormously difficult for poorer families. Women carry a double burden of oppression—as lower paid exploited labour in the workplace and as unpaid carers in the home.

Feminist abortion historian Barbara Baird writes: “If all women are to enjoy their human rights to full reproductive health care, the public health system must take responsibility for the adequate provision of abortion services; ongoing and vigilant activism is central if this is to be achieved.”[xx] She underlines the importance of the context of social change in the 1960s and 1970s, and the work of pro-choice reformers and activists, that, “transformed attitudes to fertility control and delivered liberal access to abortion by the end of the 1970s”, adding that Medicare was crucial to enabling access.[xxi]

From liberalisation to decriminalisation

In the late 1960s abortion legislation was challenged in Western societies by civil libertarians and liberal feminists, concerned about excessive state intervention in the private lives of women and doctors and in response to demand from unprecedented numbers of working women. In Victoria and NSW abortion provision was a dangerous, sometimes fatal, but lucrative black market. It was estimated 10,000 high-priced abortions were performed in Melbourne, protected by corrupt police. There was no public health system.

In Britain the 1967 Abortion Act reformed legislation relating to the first 28 weeks of pregnancy. The law also said two doctors must agree that to continue with the pregnancy would endanger the woman’s physical or mental health, or seriously risk foetal abnormality. This Act was a landmark, but still far from a woman’s right to control her own body.

In SA (1969) and NT (1973) reform succeeded following similar lines to the British Act. Failed attempts to reform WA legislation (from 1966) closed off reform in that state until 1998. Plans by individual politicians to change the laws in Victoria and NSW were rejected by the Liberal government because of the electoral realities, which included the role of the Catholic Church and Democratic Labor Party (DLP) on whom the Liberals relied for electoral preferences.

Instead of legislative reform in parliament, in 1969 in Victoria the law was tested for the first time in the courts. Judge Menhennitt presided over the prosecution of Dr Davidson on five counts of illegal abortion. He was acquitted on the basis that the abortions were “… necessary to preserve the woman from serious danger to her life or to her physical or mental health (not being merely the normal dangers of pregnancy and child birth) which the continuance of the pregnancy would entail”.

From May 1970 Sydney’s WLM along with six other pro-choice groups campaigned against the arrest of staff at Heatherbrae Clinic by ‘Abortion Squad’ police. The lively demonstrations and debates lifted the taboo and helped turn abortion into a new very political issue. By October 1971 Judge Levine acquitted the staff and adopted a similar ruling as Menhennitt.

The new political context made a difference. Under pressure from a militant social movement and needing to modernise aspects of Australian capitalism, the Whitlam Labor government of 1972-75 responded to some of the demands: it dropped all fees for tertiary education, supported equal pay for sections of the workforce, funded women’s health centres and refuges, extended the single mothers’ benefit to single parents other than deserted wives and widows in 1973, and lifted the ‘luxury’ sales tax of 27.5 per cent on contraceptives. Significantly, it introduced a public health system, then called Medibank. (Abolished under the Liberal Fraser government, it was reintroduced in 1984 by the Hawke government as Medicare.)

Some Labor politicians publicly supported abortion law reform, including the Prime Minister, and two attempted to win support for new reformed legislation for the ACT in federal parliament in 1973. Liberal and Labor parties allowed a ‘conscience vote’. Anti-abortion groups like the RTL, assisted by the Catholic Church and right-wing politicians, reacted with a huge anti-abortion mobilisation, beginning a polarising battle between pro-choice and anti-abortion forces that lasted decades. The ‘abortion bill’ was defeated resoundingly, with many Catholic Labor MPs voting against.

The WLM and socialist activists campaigned to protect the gains as the level of anti-capitalist struggle declined after the sacking of Whitlam in 1975 and through the 1980s. In 1979 when the right wing MP Stephen Lusher attempted to remove abortion from Medibank funding, he was met with a strong left-wing mobilisation and his proposal was defeated. Trade unions supported demands like maternity leave, equal employment opportunity, improved provision of childcare and affirmative action; and their peak body the ACTU supported, “access for all couples and individuals to the necessary information, education and means to exercise their basic right to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children”. This policy enabled some left-wing unions to officially support abortion as an industrial issue and to back pro-abortion campaigns.

When, in 1980, the Queensland government attempted to enact specific anti-abortion criminal legislation, the ‘Pregnancy Termination Control’ Bill, it was defeated by a mass campaign in which the trade union movement led by the local Trades and Labor Council was a crucial element. RTL again campaigned enthusiastically. In 1986, Queensland law was tested with a similar outcome to NSW and Victoria. The RTL and the Catholic Church had tried to turn back the clock but failed.

The 1990s became a very contradictory period for abortion law reform. From 1996 the Howard government, specifically Health Minister Tony Abbott, temporarily achieved an effective ban on the abortion medication, RU486; but pro-choice reformers stymied him in 2006.

At the same time anti-abortion activists were pro-active in WA where, unusually, two doctors were charged in March 1998 for performing an abortion. They had been practising under the assumption that the Menhennitt ruling applied, even though the law in WA had never been tested. The response was immediate, with pro-choice rallies, a doctors’ ‘strike’ and proposed legislation to repeal the sections of the WA Criminal Code that made abortion illegal. RTL supporters proposed alternative legislation. As explained above, the outcome saw amendments which included that an abortion must be ‘justified’ according to criteria laid down in the Health Act and doctors can be charged with a criminal offence. Anti-abortion WA independent parliamentarian, Phillip Pendal, exulted that, “over time the legislation would become a framework to implement greater restrictions”.

In the ACT in 1998, anti-abortion politicians successfully argued for lengthy counselling procedures, including a three-day ‘cooling off’ period. In Queensland in 1999, the Liberal Health and Women’s Policy spokesperson threatened to move a private member’s bill to ban late-term abortion.

The ACT situation was turned around with the removal of abortion from the criminal code in 2002. Decriminalisation was put on the agenda more widely in 2005, in response to these attacks and a more pro-active anti-abortion federal Liberal government, but also contradictorily the decline in influence of religion during the later 2000s.[xxii] It was in this period that we saw the arrest of leading Catholic George Pell, recently convicted of sex abuse, who said that abortion is a “worse moral scandal” than sex abuse perpetrated against young people by Catholic clergy.[xxiii]

The Howard era debates contributed to a new general discourse on abortion that included an emphasis on women’s maternal role and abortion being excessively harmful for women, acknowledged by both some pro-abortion and anti-abortion commentators. The right went so far as to support false and medically impossible ideas that abortion caused breast cancer, without giving up their position that abortion is ‘murder’. Pell expressed it this way: “I feel a great sympathy for women who are pushed into abortion. I feel a great sympathy of course for the destruction of innocent life, and that is one of worst—it is the worst—of evils.”[xxiv] Treasurer Peter Costello’s call to boost fertility rates and have three children—one for yourself, one for your husband and one for the nation—was indicative of the Liberal government’s position.

Nevertheless, the political environment overwhelming supported the ‘right to choose’. Katherine Betts’ analysis of changing attitudes to abortion at this time showed that 89 per cent of voters supported abortion “in certain circumstances”, including 50 per cent when women “want one”.[xxv] Labor politicians moved to decriminalise abortion, succeeding in Victoria (2008), Tasmania (2013) and later in NT (2017) and Queensland (2018). In NSW this took place under a Liberal government in 2019.

As Baird argues, while, “decriminalisation may be a precondition for the improvement of access to abortion services, it is only when public health departments take responsibility that equitable access will be delivered”.[xxvi] A relatively poor experience of access to terminations outside metropolitan areas continues.

The Guardian reported on 6 August 2019: “Seven months after the state voted to decriminalise abortion, there remains a ‘postcode lottery’ in Queensland for women … but overall the effect is being seen as positive. In … Cairns in the far north, where last year more than 10 women a month were flown interstate for procedures, doctors say the law change has had a radical effect. In other parts of regional Queensland… women’s advocacy services still hear stories about doctors treating women with disrespect.” One thing that has not appreciably changed is the number of abortions. According to Holly Brennan from Children by Choice: “We’re still seeing the same amount of abortions we’ve always had. It’s not this huge service need, it’s just that it’s treated as a healthcare issue now.”[xxvii]

Women still do not have the right to decide if and when to have a child in all circumstances—it is the state and doctors who decide on late-term abortions. It is not impossible physically or economically to allow women full freedom to control their own fertility. Yet capitalism is unlikely to grant these rights because of women’s family role. The social system can allow only limited rights for women; the questions surrounding abortion reflect the contradictory nature of women’s oppression in late capitalism.

Late-term abortions

Around 98 per cent of all abortions in Australia occur within the first 20 weeks—in most states early abortions are fairly normal and easily organised. However, there are important reasons why some need an abortion later. The main reasons are foetal demise; foetal abnormality (which often cannot be diagnosed until after 20 weeks); severe medical complications and the physical or mental health of the woman; and rape or incest. Sometimes a lack of education for a very young woman can mean pregnancy is not admitted until after 20 weeks. Those over 45 may initially mistake symptoms of pregnancy for the onset of menopause.

Newspaper reports focus on late abortion and a suspected growing willingness to terminate foetuses with non-fatal abnormalities, because this may increase discrimination against people with disabilities. But why do women feel uncertain about giving birth to a child with a disability? The Executive Director of Melbourne’s Health Issues Centre, Meredith Carter, says abortion is attractive because of, “the attitudes of our society to disability of any kind, and the low levels of support and assistance received by people to manage their own or their children’s disabilities versus the high emotional and economic costs…”. The woman’s decision to abort a foetus is not a reflection on people with disabilities. Instead it reflects a society that does not provide adequate support. We need better childcare, free of charge: instead the Liberal government presides over inadequate childcare funding and undermines public services for people with disabilities.

While very few women seek late-term abortions, it is important we support their right to decide. It is a question of a woman’s right to control her own body. No one takes these decisions lightly; they are usually forced into the situation, perhaps requiring confirmation of an abnormal foetus, but often because of delays in obtaining an early abortion. Only when we have easy access to safe, early abortion will the (already small) number of late abortions decline. Abortion must be available as early as possible, but as late as necessary.

Right to Life groups

Tiny, unrepresentative but well-resourced anti-abortion groups have influenced the restriction of women’s rights since being set up in 1969 in Australia in response to liberalisation of the laws. Their aim is to get recognition that a foetus is a human person so that the Right can argue for foetus rights over women’s rights. A foetus is not regarded as human in law.

Limited rights are constantly under threat by anti-abortion groups. While opinion polls show only a tiny minority support the anti-abortion position, parliamentarians give their arguments more credibility, reflecting the continuing, although contradictory, opposition among the ruling class to women’s control of fertility.

RTL in the US have succeeded in winning a series of court rulings to further restrict late-term abortions, impose mandatory delays and state-directed counselling, enforce parental involvement for minors, restrict health insurance coverage and deny state funding, all issues considered by anti-abortionists here.

During the 2019 abortion debate in NSW, the anti-abortion Right attempted to amend legislation to impose new procedures on doctors to preserve any live foetuses following abortion procedures. The eventual amendment failed. However, the Liberal Premier Gladys Berejiklian has indicated new legislation based on ‘Zoe’s law’ will be introduced which would make it an offence to harm or kill a foetus during the course of a crime.[xxviii] This followed the principles in an earlier law, first introduced by anti-abortionist Reverend Fred Nile. It was first proposed after Brodie Donegan, who suffered a miscarriage after she was hit by a driver under the influence of drugs in 2010, voiced her support for the change. The amendment was named Zoe’s law after the name given to her unborn child.

Yet even the NSW Bar Association opposed the Nile bill, arguing it has no legal rationale. An existing offence under the NSW Crimes Act already allows the destruction of a foetus against the mother’s wishes to be considered a crime against the woman, punishable with a maximum 25 years in jail. The Australian Medical Association and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists also opposed the amendment.

The Right tries to undermine availability and access to abortions in at least three ways: first, they are most visible in protests in street demonstrations and outside abortion clinics. Women have been frequently accosted outside abortion clinics. The laws in most states creating Safe Access Zones that ban protests within 150 metres of a clinic are a welcome step to ending the harassment of women and clinic workers. This is an issue of access to abortion not freedom of speech—as the High Court recognised when it rejected an attempt by anti-abortion activist Kathleen Club to challenge the laws. But the laws came too late for the security guard at the Fertility Control Clinic in East Melbourne who was shot dead by an anti-abortion gunman in 2001.

Second, they support amendments to legislation that restrict access to late-term abortions. By exaggerating developments in medical technologies they argue that the foetus is viable earlier than previously thought. The foetus cannot survive without lungs, which develop at 22-24 weeks of pregnancy. This sets the background for attempts to ban so-called ‘partial birth’ abortions. RTL activists in the USA argue that many late-term abortions are infanticide. In Australia in 2019, they were backed up by former Liberal Prime Minister Tony Abbott and his former deputy Barnaby Joyce of the National Party who labeled abortion as “infanticide on demand”. The D & X method can be performed successfully on a foetus of between 14-28 weeks’ gestation. Doctors have reported intimidation by laws requiring birth and death certificates for abortions done after 20 weeks.

Third, as we saw in the 1990s, and in 2019 in the NSW debate, right-wing amendments often seek to impose ‘informed consent’ requirements. The AMA Vice-President in NSW, Danielle McMullen, said: “Informed consent is a standard part of clinical practice and the concern with it being [in] the bill is that it adds confusion, and an extra layer to the process, so that termination of pregnancy is different to every other procedure we perform. We would strongly refute that and say a termination is a medical procedure like any other.”[xxix] Extra counselling for the woman can amount to duplication of requirements. Such processes may cause unnecessary delays, risking later abortion.

In NSW, anti-abortionists also raised concerns that women want to abort selectively to ensure the preferred sex at birth, although there is no evidence of this. The move partly reflected the racism of the MPs involved and was exposed by protests from ethnic communities. In other countries, anti-abortion politicians have attempted to imply that women are being disadvantaged by attempts to favour male births over females, reflecting RTL moves to appeal to women for support. NSW MPs agreed to the Ministry of Health undertaking a review after 12 months experience of the new Act to determine whether the practice of gender-based terminations occurs.

RTL get resources and social support from the Catholic Church as well as right-wing business circles. The anti-abortion position is supported by a range of politicians across the spectrum, even though official party policy is usually more liberal. For the Labor and Liberal parties, the issue is often the subject of a ‘conscience’ vote allowing politicians to vote against more liberal party policy.

From the US to Europe, racists on the rise

In the US, the right to an abortion is guaranteed by the famous 1973 Supreme Court ruling in Roe v Wade. This supported the privacy rights of the woman (and her doctor) to decide on whether to abort or continue a pregnancy before the end of the second trimester. The strong implication is that viability is likely around then (26-28 weeks).

In 2017, President Donald Trump’s Protecting Life in Global Health Assistance policy expanded the ‘global gag’ order, applying it to recipients of any US global health funding, totalling an unprecedented $8.8 billion. In 2019, the Trump administration announced a further expansion, “restricting ‘gagged’ organizations from funding groups that provide abortion services and information, even though those organizations don’t get any US aid. This means that organizations, donor governments, and funders will be bound by a US government policy, even if they do not accept any US government funding.”[xxx]

In 2019, seven US states—Alabama, Kentucky, Ohio, Georgia, Mississippi, Louisiana and Missouri—made head-on challenges to federal law by passing laws that move the cut-off point for a legal abortion deep into the first trimester, some making no exceptions for rape or incest. They permit abortion only if woman’s life is at risk or if the foetus cannot survive. Some laws ban abortion as soon as a so-called ‘heartbeat’ of the foetus can be detected, which some say can be heard as early as six weeks (there is no proof of an actual heartbeat or that a heartbeat is a sign of actual life, but simply an electrical response).

Alabama has the most far-reaching legislation—abortion is banned at any stage, from conception; there is no exception for rape or incest. These new state-based laws face immediate court challenge because they directly conflict with the federal Supreme Court ruling. But by passing extreme laws the hope is that the Supreme Court will have to revisit and may overturn Roe v Wade.

The rise of the far right globally has produced a new threat to our rights to abortion. Anti-abortion groups like the Christian Right and other far right groups have begun to campaign internationally to strengthen right-wing anti-woman attitudes about the family. The link between racism and sexism was illustrated in the manifesto of the Islamophobic Australian terrorist who massacred 51 Muslims in Christchurch, who wrote of the concept of the ‘Great Replacement’, the idea that non-whites are ‘invading’ western, white nations. While, as the New York Times says, this is a conspiracy theory with no validity, far right ideologues have used the concept as a rallying cry globally to attack feminism and immigration.

This is not a new idea for racists. Nazi propaganda accused Jewish people of attempting to replace the white/Aryan race, and now the far right accuses Muslims. Abortion politics fit neatly here—they say it is the responsibility of white women to increase their fertility to ‘save the race’.

Tom McCarthy in The Guardian noted on 7 July 2019 that: “Evangelicals feel Trump has kept his covenant with them by nominating conservative judges to federal courts and to the supreme court; by tacitly supporting abortion bans; by supporting Christian universities and organisations that profess a moral objection to same-sex marriage or contraception; by supporting religious dispensations from anti-discrimination laws; by moving the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem and other measures. Meanwhile, Trump has addressed a central concern for white evangelicals that they are losing influence as a group and that the sun is setting on the United States they dream of—a nation that is white and Christian in its majority and in its essence.”

According to The Guardian, Trump, “told MSNBC’s Chris Matthews that women who seek abortions should face criminal punishment”, although the National Right to Life, “explained the party line: ‘Unborn children and their mothers are victims in an abortion’.”[xxxi]

The ideas of eugenics and racial purity were discredited with the defeat of Nazi Germany, and scientists have shown that the genetic variation between supposed racial groups is far less than that within each population. There is only one race—the human race. However, European anti-abortion groups are teaming up with racist and far right groups to strengthen their electoral influence, using abortion as a political weapon.

Australian right-wing groups are connected internationally via the World Congress of Families (WCF), whose origins are in the US in 1997. The Southern Poverty Law Center in the US regards it as hate-group because of its anti-LGBTIQ+ and anti-abortion attitudes. This seems a fringe organisation—Larry Jacobs, a supporter of Russia’s homophobic laws and WCF director in 2014, said: “If you just do three things correctly, 90 per cent of the time you will never live in poverty—graduate from high school, get married and have children.”

However, this is the group gaining endorsement from a number of governments in Europe, including Poland, Italy and Hungary. They campaign for a conservative definition of the family—a man and his wife, plus presumably lots of children, linking homophobia, sexism and racism. The WCF campaigns against women’s rights to birth control. They recently met in Verona, Italy, welcomed by the anti-abortion city council. A 30,000-strong demonstration of feminists also met them.

While abortion has been legal in Hungary since 1992, the Viktor Orban government is chipping away with an anti-immigration, anti-abortion mantra: “Hungarian children rather than migrants.” Orban altered the constitution to include: “The life of the foetus shall be protected from the moment of conception.” The government has granted two hospitals, owned by the Catholic Church and the Reformed Church respectively, 7.8 billion forints for gynaecological services, with the proviso that no abortions can be performed. Many object. According to a survey by Median: “72 per cent of churchgoers thought that in cases of financial stress abortion was an acceptable alternative … The same group of people believed that the abortion pill that … [a catholic party] … torpedoed a year before was an acceptable … method of birth control.”

In Matteo Salvini’s Italy, abortion has been legal for the last 40 years but is becoming increasingly difficult to obtain because of the numbers of doctors who cite conscientious objections on religious grounds; many other doctors are becoming fearful of the stigma surrounding abortion and potential damage to their careers. In Poland abortion is banned except for victims of rape and if there is a threat of a woman’s death or the foetus is irreparably damaged. A recent move to completely ban abortion was prevented by massive pro-choice demonstrations.

The far right has made substantial gains with Islamophobia its strongest ideological weapon. However, this form of racism was not initiated by the right, rather the liberal and social democratic mainstream parties. Its significance grew over the period of the long depression since 2008, during which the European governments and media have led the Islamophobic arguments against immigration, attempting to shift the blame for economic problems from themselves to the most powerless. Now, the European right looks to the abortion politics in the US as an issue defining political allegiances, hoping to capitalise on a toxic combination of racism and anti-woman violence.

However, none of these ideas is uncontested—there is a polarisation, to right and left. Racism and sexism cannot be separated in the necessary fight for equal rights, but the struggle requires a class analysis and the mobilisation of working-class people, the 99 per cent, to be effective.

Fighting back—for free, safe abortion on demand

Fundamentally the issue is about a woman’s right to control her own body. Without that right all women remain oppressed.

Those from different classes are affected differently, because people’s experience of oppression is structured by class relations. The rich have always had easy access to safe abortion and other privileges. Poorer and working class women need state-funded or free abortion, or they don’t have safe access at all. Rather than fight for complete reproductive freedom, ruling-class women have a greater interest in maintaining and winning more privileges within capitalism. Feminism’s call for women to unite always comes up against this fundamental class divide. That’s why campaigns for abortion rights have always been split: between those who can live with reform of the laws, and those working class and poorer women who need repeal of the laws and free abortion on demand.

Many working class people look to Labor as their political representatives. The ALP Platform pledges to, “support the rights of women to make decisions regarding reproductive health, particularly the right to choose appropriate contraceptives and termination and ensure these choices are made on the basis of sound social psychological and medical advice …” The Victorian and Queensland Labor governments led the decriminalisation process in their states. But Labor politicians have shown themselves willing to compromise with the Right, often using the ‘conscience vote’ which allows the rare practice of voting against the party platform. Thus, as ALP prime minister, Julia Gillard voted against a bill for marriage equality (which became party policy in 2011) in 2012, delaying the eventual same-sex marriage victory in 2017.

History shows we cannot rely on parliament. The most successful struggles for abortion rights have linked mass mobilisations to the support of the trade union movement. In Queensland in 1980, many unions recognised that abortion was an industrial issue, because without the right to choose women didn’t have the same access to jobs. Male and female unionists showed that all workers can defend women’s rights; and a series of unions, including male-dominated ones, passed motions condemning the anti-abortion bill. A group of male transport workers stopped work to join a pro-abortion picket. The social power of unions is important to any campaign. Winning union support opens up a wider audience, attracts larger numbers to protest rallies and points in the direction of industrial action.

Capitalism fosters the oppression of other groups in society—discrimination against Aborigines and Asians, and LGBTIQ+ people, for example—deliberately creating divisions among workers. Oppression therefore creates daily obstacles to working class unity. Yet all those who are oppressed and exploited face a common enemy, and ending that common exploitation and oppression involves a common struggle. The struggle for abortion rights is bound up with the struggle to end the system—it is a class issue as well as a gender and race issue. Women’s permanent role in the workplace has opened up a greater role in social and political life, increasing their confidence to raise these demands. Women workers have joined trade unions in huge numbers and are prominent in class struggles across the world.

Socialists support a woman’s right to choose when and if to bear children. It is they who bear the emotional and physical cost of carrying an unwanted pregnancy, and therefore they should have the right to decide whether or not to do so. So long as the right to abortion is restricted by society, women are not free to control their own bodies and their own lives.

All anti-abortion laws should be repealed. Abortion should not be subject to the criminal codes, and doctors should not have over-riding decision-making powers. Rather, all women should have access to safe medical conditions for all appropriate procedures, subject to normal health provisions. The right to choose also depends on the right to access free, safe and reliable contraception and sterilisation for men and women. Socialists totally reject forced contraception, abortion and sterilisation, especially the racist practice of imposing these on Aboriginal and disabled people.

Fertility rights depend on a health system based on needs rather than profits. Abortion must be available free of charge and on demand, so that women can decide when to have an abortion. This is essential for workers and the poor in particular. In Australia this means abortions provided free of charge in public hospitals, or full rebate via the Medicare system, so that women can choose a clinic or hospital. Travel costs should be compensated.

While abortions are safer in the first three months of pregnancy, there are many reasons for deciding on a later date—deformity of the foetus, rape, fear, not being aware of pregnancy, or parental pressure. Women should have the right to decide on abortion at any time during the pregnancy, as early as possible, but as late as necessary. While we should all have access to high-quality counselling, socialists totally reject abortions being delayed by imposed counselling against the wishes of the woman.

The right to free and safe abortion on demand remains a central element in the fight for women’s liberation. Women have won this right only once—during the revolutionary period in Russia after the socialist revolution of 1917. Abortion rights were granted in legislation giving women equal economic, political, legal and social status with men. Society was to take economic responsibility for childbirth and childcare, and women gained the right to control whether or not they would have children. Unfortunately, the rise of the Stalinist state at the end of the 1920s created a new state capitalist dictatorship and the end of women’s equality and legal abortion. Women later regained access to abortion in Russia and Eastern Europe but without adequate access to contraception and other social supports.

Abortion remains a hot political issue—not because it’s a dangerous procedure but for ideological reasons. The immediate danger in Australia is not outright prevention of abortion, but further restrictions on access. Targeting late-term abortions has been a stalking horse for clamping down on abortion rights in general. Our right to choose remains restricted in every country and will remain so until capitalism is replaced by a socialist system based on human need.

For

system change we need more protests like the women’s marches and teachers

strikes in the US, the ‘yellow vest’ street protests and strikes in France and

the mass movement in Hong Kong. We need to unite all the different struggles,

like the protesters in Brazil where tens of thousands joined the indigenous women’s

‘March of the Margaridas’ in August to denounce President Bolsonaro as “misogynist,

racist and homophobic”. Their concerns ranged from rampant deforestation in the

Amazon rain forest and education cuts to the culture of misogyny and

machismo that plagues the country. It is our fight, too.

[i] https://www.sbs.com.au/news/abortion-has-been-decriminalised-in-nsw-and-here-s-what-will-actually-change, accessed 2 October 2019.

[ii] For updated information on the Australian situation see Children by Choice website: https://www.childrenbychoice.org.au/factsandfigures/attitudestoabortion.

[iii] The 2003 Australian Survey of Social Attitudes (AuSSA) found that 81% of those surveyed believed a woman should have the right to choose whether or not she has an abortion. The 2003 AuSSA also found that religious belief and support for legal abortion are not mutually exclusive, with 77% of those who identify as religious also supporting a woman’s right to choose: https://www.childrenbychoice.org.au/factsandfigures/attitudestoabortion

[iv] Ibid.

[v] International information, World Health Organisation: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion/en/

[vi] For statistics and regularly updated international information about abortion, access the websites of the Center for Reproductive Rights: https://reproductiverights.org/document/worlds-abortion-laws-supplemental-publications, and the Guttmacher Institute: https://www.guttmacher.org

[vii] https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-united-states

[viii] http://dpoa.org.au/factsheet-sterilisation/

[ix] https://www.phaa.net.au/documents/item/256

[x] https://www.alp.org.au/media/1539/2018_alp_national_platform_constitution.pdf

[xi] Medical abortion is a two-stage/two-tablet process. The first blocks the hormone necessary for the pregnancy to continue. This is followed 24-48 hours later by a second medication which causes the contents of the uterus to be expelled. It has a high success rate, up to 98%. Up to 8 weeks pregnancy, you may be eligible (not legal in SA or if U-16) for a medical abortion by phone, tele-abortion. After a blood test and ultrasound, and a successful consultation over the phone with a doctor, the abortion medications are sent by courier, usually there’s a 24/7 nurse aftercare service. Check relevant websites for details – this is only a summary.

[xii] Judith Ireland, ‘“Confusion, huge disparity”: What Australian women face trying to access abortion’, The Guardian, 12 August 2019.

[xiii] https://greens.org.au/sites/default/files/2018-06/Greens%20-%20Access%20to%20Affordable%20Abortion%20and%20Contraception.pdf

[xiv] https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/talking-to-a-brick-wall-rural-women-struggle-for-medical-abortion-access-20190920-p52tai.html, accessed 2 October 2019.

[xv] R Sifris and S Belton, ‘Australia: Abortion and Human Rights’, Health and Human Rights Journal, 2017, 19(1): 209-220.

[xvi] Deborah Brennan, The Politics of Australian Child Care, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p.59.

[xvii] https://www.employment.gov.au/newsroom/statistical-snapshot-women-australian-workforce. ‘The January 2019 labour force statistics indicated that there are 5,983,900 women employed in Australia … the number of employed men is currently 6,767,900’; the female participation rate (the number working or looking for work) was 60.7 per cent, and for males it was 70.9 per cent.’ (ABS 2019, Labour Force), accessed 1 October, 2019.

[xviii] ‘Childless by Choice’, sundaylife, The Sunday Age, 18 August 2019.

[xix]https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/036, accessed 1 October 2019.

[xx] Barbara Baird, ‘Decriminalization and Women’s Access to Abortion in Australia, in Health and Human Rights, Vol. 19, No. 1 (June 2017), p. 197.

[xxi] Ibid., p. 199.

[xxii] https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/2f762f95845417aeca25706c00834efa/fa58e975c470b73cca256e9e00296645!OpenDocument

[xxiii] Sydney Morning Herald, https://www.smh.com.au/national/ill-say-it-again-abortion-is-a-worse-evil-pell-20020803-gdfidn.html, August 3, 2002, accessed 2 October 2019.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Betts, K., ‘Attitudes to Abortion: Australia and Queensland in the Twenty-first Century, in People and Place Vol. 17, No. 3: 2009.

[xxvi] Baird, ‘Decriminalization …’, p. 198.

[xxvii] https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/aug/06/queenslands-abortion-law-change-improved-access-but-postcode-lottery-remains, accessed 2 October 2019.

[xxviii] https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/nsw-government-to-debate-zoe-s-law-to-criminalise-harm-to-fetuses-20190818-p52i7o.html, accessed 2 October 2019.

[xxix] https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/sep/25/abortion-decriminalisation-bill-passes-nsw-upper-house

[xxx] https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/what-global-gag-rule

[xxxi] https://townhall.com/tipsheet/christinerousselle/2016/03/30/prolife-orgs-condemn-trumps-comments-on-abortion-n2141223, accessed 3 October 2019.