The horrific rape and murder of 22-year-old comedian Eurydice Dixon, in a park just hundreds of metres from her house, has galvanised a discussion about the extent of violence against women in Australia—and how, so often, women are blamed when they are attacked or assaulted.

In the immediate aftermath of Eurydice’s murder, the Victorian police reproduced the standard “stranger danger” and victim blaming script, telling women to “take responsibility for your safety” and “… just make sure you have situational awareness, that you’re aware of your surroundings … If you’ve got a mobile phone, carry it; if you’ve got any concerns, call the police.” A Herald Sun headline declared that Dixon had “strayed into killer’s orbit” while The Australian thought that the first line of their major report should declare she, “wore a blue flower in her hair on the night she was killed”. A memorial to Dixon in Princess Park, where she was murdered, was vandalised.

This time, however, the Victorian police and the conservative media have been met with the impatient outrage of women who are sick and tired of being made to feel responsible for the violence and sexism visited upon them. As so many women have pointed out, they have “situational awareness”—the problem is the situation.

Ten thousand people joined a candlelight vigil in Melbourne, while thousands joined others around the country.

In the era of #metoo, there is a growing awareness of how commonplace harassment and assault are for women. One in five women has experienced sexual assault in Australia; one in three, domestic violence.

Most often they are committed by people known to the victim. In fact the majority of cases of violent sexual assault and murder are also committed by someone known to the victim.

Qi Yu, a 28-year-old woman from Campsie, Sydney has been missing since 8 June, presumed dead—and her male housemate has been charged with murder. Yet Yu’s case has received comparatively little attention.

The Australian Domestic and Family Violence Death Review Network assessed the data on 152 domestic murders in Australia between 2010 and 2014, and found that 80 per cent were committed by a man against his former or current female partner.

Domestic violence and rape are not taken seriously by the legal system. Between 2009 and 2010, 3500 rapes were reported to the Victorian Police. Of these cases, just 3 per cent resulted in a conviction. In many cases, it seems that police did not pursue an investigation at all.

In seeking to turn the victim blaming script around, many are imploring that the focus be on male violence.

Thankfully, we have not seen strong calls for more CCTV and stronger bail laws, as we did when Jill Meagher was raped and murdered in Melbourne in 2012. There was CCTV where Eurydice Dixon was murdered, demonstrating that more surveillance is not the key to safety.

It is important to encourage men to challenge sexism and violence—in any workplace, classroom, bus, or train. Everyday sexism takes a grating toll, and solidarity is necessary to fight it. Just like taking up racism or homophobia, it is part of undermining the prejudices and bigotry that divide us.

Yet that alone will not take us very far as a strategy for social change. Focussing solely on a strategy of “education” draws attention away from the real causes of structural sexism and violence that have to be fought.

Sexism and the system

Sexist attitudes and ideas are a product of the system. The role women play within the nuclear family, shouldering the majority of childcare and housework, is of enormous benefit to capitalism. It means that the reproduction of the labour force the system requires takes place at no cost to big business and the rich. Capitalism also benefits from the gender pay gap, which sees women in the workforce paid less than men.

This is the source of the pervasive sexist stereotypes of women as more caring, accommodating and emotional.

There is a reason why conservative politicians are also comfortable with proposing individual behavioural change as the solution to sexism and violence. Malcolm Turnbull, speaking to parliament, declared, “What we must do as we grieve is ensure that we change the hearts of men to respect women …. [we must start with] with the youngest men, the little boys, our sons and grandsons”.

Yet Turnbull joined a gender panic around Safe Schools, a program that involves questioning harmful gender stereotypes, and took away its funding. So much for starting with “the youngest men”.

His former Deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce, has consistently opposed abortion and marriage equality.

It was Turnbull who last year threatened community legal centres, which provide essential support to women fleeing violent homes, with $56 million in cuts, only backing down after a community campaign.

Women most at risk from domestic violence—Aboriginal women, pregnant women, young women, women with disabilities, women in financial hardship—have all been attacked by Coalition policies.

Family violence is the leading cause of homelessness amongst women, but since 2011 the number of homeless people has increased 14 per cent, first under Labor and then the Coalition.

The Coalition’s refusal to raise unemployment benefits has left single mothers poorer and poorer, on the back of cuts to their payments under the Gillard government.

So often, it is society’s elite institutions where violence against women is encouraged—think about university colleges, the sporting codes, the Navy, and the Catholic Church. These institutions are tied to the ruling elite in business and politics by a thousand golden threads, and they rarely face sanction without huge effort.

“Starting a conversation” about domestic violence, as Turnbull claimed he wanted to in 2015, is a much cheaper option than doing anything to stop it. Unlike funding the social services women need to secure their independence outside relationships or marriage, “starting a conversation” is free.

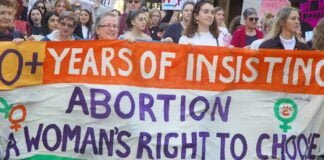

This is why the response to Eurydice Dixon needs to go further, and deeper, than simply saying, as Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews did, that men need to change their behaviour. It also needs to be about fighting to close the gender pay gap, for better parental leave, for full decriminalisation of abortion in every state, for domestic violence leave, for stronger laws around pregnancy discrimination, for better union rights, and so on. These are just some of structural factors that help to reproduce the idea of women’s inferiority, and that women and men have an interest in fighting together.

It is also important for fostering a sense of unity and strength, rather than reinforcing the sense of danger and insecurity that women can feel in a hostile world.

At a time like this, we cannot grieve with the Malcolm Turnbulls of the world—instead, we need to unite against them.

By Amy Thomas