Preamble

Sexism is as alive as ever. The movements in the 1960s and 70s won gains and transformed women’s lives, but women continue to suffer from unequal pay, gendered and fewer job opportunities, inadequate childcare, objectification and sexual violence. Australia’s first female Prime Minister Julia Gillard sparked public discussion about both the gains for women and ongoing misogyny in society.

Today there is more formal equality between the sexes, and more opportunities for women to occupy positions of power, but ordinary women’s lives remain marred by oppression. Working mothers especially suffer a ‘double burden’ of household labour and child-rearing on top of the daily grind in the workplace. The immense difficulty faced by single mothers is an ongoing reminder of the burdens that women are expected to bear. At the same time, women also continue to live with the reality and fear of sexual harassment and rape. The death of the Delhi gang rape victim in December 2012 galvanised collective outrage against sexual violence in India, sparking months-long, widespread protests that throughout the region.

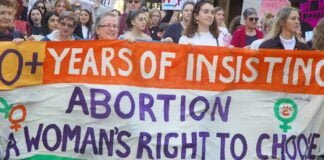

At the same time, women are blamed for such sexual harassment and rape. In 2011 a Toronto police officer told students not to dress like ‘sluts’ to avoid being targeted – the comment that sparked world-wide ‘Slutwalk’ protest marches. As the backlash against the gains of the women’s movement has grown, there has been an international resurgence of new feminist movements trying to grapple with women’s oppression. This is welcome and necessary, and socialists need to participate.

In these movements illusions in formal equality and the idea that liberation can be equated with putting women into positions of power remain strong. Patriarchy, identity politics, intersectionality and privilege theory still have a foothold, particularly on the campuses. Building the strongest possible resistance to sexism requires a clear analysis of its causes and the possibility for its overthrow. This document sets out the basic points of Solidarity’s socialist analysis of women’s oppression.

1. Oppression is a social phenomenon

Oppression is a social phenomenon – it is institutionalised discrimination, facilitating the exploitation characteristic of capitalist society.

In the workplace, women’s oppression is manifested in the gender division of jobs, lower wages, discrimination in hiring and promotion and sexual harassment. In other spheres of society it is manifested in the family and the social constructs around it, the legal system, conditioning in schools, religion, the media, etc.

2. Women’s oppression arises with class society

Women’s oppression predates capitalism—in fact it has been a feature of all class societies. Yet, the idea of a “patriarchy”—that men have always ruled over women—is ahistorical. This idea cannot explain the historical differences in the relationship between women’s oppression and the various kind of social organisation that have existed; nor can it explain the fact that the ruling class comprises both men and women. The existence of egalitarian pre-class societies in which there was no domination of women shows that there is no biological basis for women’s oppression.

The particular form and social expression of oppression are moulded by the prevailing class relations. With the development of class societies, ruling minorities began to control and accumulate surpluses produced by the majority. The stability and renewal of these ruling classes and their accumulation of property, wealth, and power over time placed a new importance on inheritance and therefore control of reproduction. In different class societies, the experience of women and the role of the family has been quite different. The development of capitalism has both reinforced and privatised the role of women and the nuclear family in maintaining and reproducing workers, and also breaks down traditional roles by recruiting women in waged labour. Women’s oppression today is a product of capitalist society – not “patriarchy”. To end women’s oppression, ultimately, the capitalist system must be smashed.

3. Sexism

As Marx argued, “The ruling ideas of society are the ideas of the ruling class.” The institutionalised discrimination against women in capitalist society, sexism, also manifests in a set of ideas, and behaviours that derive from those ideas—that women are inferior to men, submissive, naturally nurturing, more emotional, and so on.

Both women and men are conditioned through their up-bringing to accept and reinforce these prevailing ideas. This conditioning is not separate from capitalist society but is an integral part of it. These ideas derive from the oppression of women, and at the same time, they justify the oppression of women.

4. Class

While all women in capitalist society are oppressed, ruling class and working class women experience oppression differently. It is the class distinctions in capitalism that are decisive in the material experience of oppression. For working class women, oppression reinforces the exploitation of them and their class, whereas for ruling class women their experience of oppression is contradicted by their role in the exploitation of both working class women and men, and the material and ideological benefits of sexism for the ruling class.

Gail Kelly, the CEO of Westpac, is often lauded as a model of the successful career woman, and someone who has broken the glass ceiling. But Gail Kelly the female CEO has nothing in common with the female tellers who are pushed out of jobs or pushed into part-time and casual employment— at the same time as part-time work is promoted as being “family-friendly”.

There is no doubt that Julia Gillard was the subject of sexist jibes in the media and from Liberal politicians and such sexist attacks must be opposed; they are disgraceful indications of the sexism that permeates the media and society. However, Julia Gillard has done more to contribute to sexism and women’s oppression (think opposition to same sex marriage, cutting single parents benefit, imposing the Intervention) than to fight it.

Anna Bligh, the Labor left premier of Queensland, would do nothing to take abortion out of the state criminal code and allowed a young couple to be prosecuted in 2010 for procuring a medical abortion.

The material situation of ruling class women conditions and mitigates their experience of oppression in other ways too – for example abortion has almost always been available to ruling class women.

Ruling class women benefit from the intensified exploitation and oppression of working class women. For this reason there is no common ground between all women in the fight against oppression—there is no “sisterhood”.

To the extent that ruling class women fight at all they fight for equality with their male ruling class counterparts, not for equality and liberation of all. This is a distinguishing feature of bourgeois feminism throughout its history and has manifested itself in the women’s movement in the attempt to equate women’s liberation with getting women into positions of ‘power’.

In the fight for suffrage in Britain for example, Emmeline Pankhurst was quite prepared to accept property restrictions on the vote for women and was very hostile to Sylvia Pankhurst’s East London Federation of Suffragettes because it was “too working class…too democratic.” Middle class feminists were disgusted at the way working class women joined with working class men to celebrate International Women’s Day in Russia in 1912: “The day did not protest at all against the subordinate position of wives in relation to their husbands. They spoke primarily of the enslavement of proletarian women by capital.”

The fight of working class women against oppression tends to lead to a fight against capitalism, and vice versa. Women workers have played, and continue to play a major role in mass union and revolutionary struggles.

5. Autonomous organising is not an anti-sexist principle

Separate women’s meetings emerged as a tactic associated with the early phase of the women’s liberation movement to push for greater recognition of women’s oppression and for women to play a greater role in social movements.

While women, or any other oppressed group, have the right to meet separately, whether or not to do so is an entirely tactical question that can only be decided in the specific circumstances.

However, many people concerned with women’s liberation now advocate “autonomous organising” as a principle. It is often argued that women organising separately at least temporarily frees them from oppressive social relations, or that men could not possibly understand women’s experiences no matter how sympathetic they may be.

The arguments behind this are that a) women should have responsibility for women’s issues; b) women have common experience of oppression regardless of class; c) men will always dominate women or spaces; d) that women are immune from sexist and other hierarchical conditioning; and e) that the experience of oppression itself gives a superior understanding of how best to fight it.

Generally autonomous organising involves isolating women and insisting that women have responsibility for “women’s issues” rather than generalising the struggle against women’s oppression and ensuring that women play a leading role in every struggle.

Women’s oppression arose with the emergence of class society. A person’s class position determines their relationship to oppression. While both women and men carry the socialisation of sexism, and hold sexist ideas, these ideas can change in struggle. A political conviction to fight sexism can be held by women and men and is not influenced by gender.

6. Do men benefit?

It is clear that men have advantages over women in capitalist society. But many feminists see that as the cause of women’s oppression rather than a symptom.

Whatever advantages working class men might have in capitalist society, they have no material interest in maintaining the oppression of women. Similarly, white people in general have advantages in Australian society compared to the racism experienced by Aborigines or migrants. But it is the ruling class and its institutions, not white people, that are responsible for the racism of Australian society.

Indeed, just as the white working class has every reason to join the fight against racism, working class men have every reason to join the struggle against women’s oppression. The lack of childcare affects both women and men; restrictions on abortion rights affect women and their partners; the objectification and commodification of women’s bodies results in alienated relationships that affect both men and women in forming relationships; and it is the capitalist class that benefits from women’s lower pay, not men.

The role of the family and women’s primary responsibility for domestic labour can only be understood by understanding the benefit of the family for capitalism as a whole. Similarly, while it is true that individual men carry out some of the most obvious sexist crimes against women—rape, sexual assault, domestic violence—these crimes are a manifestation of sexism in capitalist society not the cause of women’s oppression.

Because working class men have no interest in maintaining women’s oppression, they are potential allies and can be won to the struggle against women’s oppression. This is not automatic. Capitalism encourages men to believe that they do benefit from women’s oppression and to accept ideas that woman are subordinate. Therefore there has to be a conscious determination to overcome the divisions encouraged by the capitalist class and to challenge sexist ideas and sexist behaviour whenever and wherever they arise.

6. Reforms, struggle and liberation

Reforms don’t win liberation, but the struggle for reform is essential to improve the conditions for women and to change ideas. Despite the gains of the women’s liberation movement, women’s oppression has not disappeared or somehow begun to whither away under the influence of previous advances. While contraception and the sexual revolution have given a greater degree of freedom to women on the one hand; on the other they have resulted in a different kind of pressure to conform to “acceptable” capitalist norms of sexuality.

However, women are today a greater proportion of the workforce, which gives women a greater independence and increases the potential for women to raise demands and fight collectively as part of a class fight. Nonetheless, the on-going double burden on women remains—as well as the gendered division of labour, part-time work, lower pay, the lack of child care, access to abortion, etc—which continues to constrain women’s role in society.

Legislative reforms that supposedly give equal rights under the law only reveal the extent to which oppression cannot be measured by “legal rights”. Capitalism has managed to accommodate and incorporate much of the women’s movement so that while significant gains have been made, women remain oppressed.

Indeed the historical gains of women workers and the women’s liberation movement are under increasing attack, and in the last few decades the advances made by the women’s liberation movement have been rolled back. Women’s reproductive rights are still contested and abortion remains in the criminal code of most Australian states.

Sexist stereotypes of women as sex objects have become increasingly acceptable in the media, advertising and film. “Raunch culture” has turned the advances of the women’s liberation movement on its head – for example, repackaging stereotypes of sexual exploitation such as Playboy or pole dancing as examples of empowered female sexuality.

Although sexism is socialised, people are also conscious beings and capable of “making their own history”. In general, both men’s and women’s ideas are challenged when they are involved in serious struggles. Struggle forces people to question the way society is organised, not just so they can improve their own material conditions but because they begin to develop solidarity and break down divisions between themselves.

When women strike, for example, their action can pose questions about their traditional role in the family, while their confidence from activity in the workplace can also be taken back into the home to make changes there. Likewise, struggle by a mainly male workforce can also challenge traditional ideas of the role of women, as questions of their active participation in building solidarity and involvement on picket lines, etc, are raised.

It took militant political struggles to win the reforms we have now. Without such struggles, women would be a lot worse off. The fact that there are not many strong campaigns for women’s rights at the moment doesn’t mean we can’t do anything.

It is essential that we support and involve ourselves in the struggles that do occur. This is not just because sexism can be challenged and improvements can be won, but because struggle is key to changing people’s ideas and changing the society in which we live.

7. How we organise

This means taking seriously political education about women’s oppression, and to consciously take steps to raise issues of women’s oppression and develop women’s role in the struggle.

We understand that the consequences of social conditioning have a particular impact on women that can make it more difficult for them to become confident members and leaders of Solidarity, in the workplace, within unions or in social struggles.

This requires consistent and conscious action to encourage, develop and actively promote women members and to give particular attention to raising awareness and consciousness of women’s oppression both within the group and wherever we are active.

In the magazine we are concerned to highlight and raise the profile and awareness and profile of women in every kind of struggle. There is a particular priority to relate to women who are in struggle, and encouraging women to play a role in the struggle whatever the demand or the particular struggle may be. We explicitly raise issues and build campaigns that highlight women’s oppression and fight for demands such as child care, abortion rights, against casualisation, the welfare-to-work attacks on single parents (and the disabled) and for such issues to be taken up as class demands.

Separating women’s issues from the general demands of the workplace or movements leads to regarding women as victims, relegating women’s issues to a secondary concern, to ensuring that women’s issues remain the responsibility of women and tends to exclude or at least limit the role of women in the campaigns.

We fight both for women to take leading roles in any campaign and for anti-sexism to be part and parcel of any campaign. For example, we fight for the specific concerns of women workers to be an integral part of working class campaigns against the anti-union laws.

The fight in every struggle can only be stronger for the greater involvement of women leading the fight on campus, in the workplace, and in the social movements.

For socialists the fight against sexism and for women’s liberation is an integral and necessary part of the struggle against capitalism itself.

Adopted Solidarity national conference, February 2014