There was an outpouring of community concern at the rape and murder of ABC journalist, Jill Meagher. The circumstances of her death—while walking home after a night out—were shocking. Much of the outpouring following it has voiced concern at violence against women.

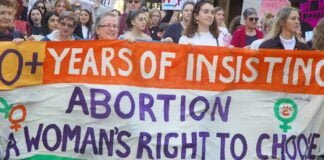

The march in Brunswick that drew 30,00 people involved women, men, and families expressing sympathy for Jill and her family. If the march has made women feel safer about walking alone in Brunswick (and elsewhere) then it has achieved something.

But the community grief and the march raises wider questions about how to respond. ABC presenter Jon Faine set a good example, saying, “Jill’s death must not come to define us. That’s not what it’s like to live in the Melbourne that we know… But Jill wouldn’t want us triple locking the door and installing closed-circuit televisions everywhere as if we live under siege, because that’s not what it’s about.”

It is easy for such events to lead to blaming men in general, and to see marches as a protest against “male violence”. The very nature of protests around such violence also tends to feed calls to strengthen state powers, rather than mobilise women and men against the institutions that are responsible for sexism. It is worth asking the question, “Who/what are “Reclaim the Night” marches actually reclaiming the night from?”

Although there have been many calls for more CCTV cameras, thankfully, there have been few demands for more police. In particular it is reassuring that, so far, there have been no calls for longer sentences for perpetrators, or ugly scenes at court appearances. These do nothing to make women safer, reduce the level of rape or the social objectification of women.

The police are notoriously dismissive of complaints about rape and sexual assault and often fail to follow through on complaints. Only one out of six reports of rape proceed to prosecution. Rape trials all too often put the victim on trial.

This was shown when Melbourne nurse Stacey Scaife came forward after the recent tragedy to say she had twice been threatened in the same area as Jill was abducted. Despite reporting the incidents to the police in December, no record or further investigation was made. And neither increasing the number of police nor security cameras will do anything to address the majority of sexual violence, which actually occurs in the home.

An increase in security cameras could however lead to more police harassment of Aboriginal people, young people and the poor—as well as political protesters.

Rape and the home

Rape and sexual assault are two of the most underreported crimes in Australia. Some researchers have estimated as few as 10 per cent are reported to police.

A recent Parliamentary report showed that in 2005, 1.6 per cent of women in Australia experienced some form of sexual violence in the previous 12 months.

Approximately one in five women had experienced sexual violence at some stage in their lives. The statistics are terrible but they do show that it is only a minority of men who perpetrate sexual violence.

The fact that in Jill Meagher’s case the attack was carried out by a random stranger however, has reinforced the myth that strangers are responsible for most rapes.

But it is well established that most violence towards women comes from people they know.

The ABS publication Recorded Crime Victims 2003 shows that 78 per cent of female victims of sexual assault knew the offender. A 2005 Australian Institute of Criminology report found that 49 per cent of murders of women occurred as a result of a domestic altercation.

No means no

What the march in Brunswick did show that there is a greater public acceptance of the 1960s slogan, “However we dress, wherever we go—yes means yes and no means no.” It has become far less acceptable to blame women for rape and sexual violence.

But there has been a backlash against these ideas and the wider gains of the women’s liberation movement. The police, the courts and the media continue to deal with, and portray, rape victims as if they themselves are to blame.

The recent revelations of the entrenched sexism in the Defence forces are examples of the way sexism permeates the institutions of Australian capitalism.

The Gillard government has reinforced the traditional view of women’s role in society though its on-going opposition to same-sex marriage on the one hand, and its victimisation of single mothers by pushing them onto the dole, on the other.

Understanding how capitalism institutionalises sexism and women’s oppression through government, the media, the education system and so on, is the key to understanding how to fight it.

By Ian Rintoul