One hundred years on Phil Chilton argues that the Dublin lockout was a model of effective, militant unionism—but it also showed the problem of the union bureaucracy

In August 1913 Dublin tram drivers abandoned their trams in the street after their employer, William Martin Murphy, sacked union members and declared war on the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. The Dublin Lockout, as the dispute that developed became known, eventually involved 25,000 workers.

It was the most important industrial struggle in Irish history and a high point of the militant syndicalist unionism of the early years of the twentieth century. One hundred years later it still provides important lessons for those who continue to fight what Irish socialist James Connolly called the “fierce beast of capital”.

The Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) was led by Jim Larkin. Larkin was a union leader who had learnt the value of organisation and solidarity among workers through bitter experience. In 1905 he had been swept up in the Liverpool docks strike. That strike was defeated when scab workers were brought in and saw Larkin sacked as a ringleader.

He was taken on by the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL) as an organiser for the ports of Scotland and Ireland. In 1907 he brought Belfast dockers out on strike, and stymied the employers’ hopes of using scab labour to break the strike by persuading carters not to cross the picket lines. Employers might be able to use scabs to unload the ships but without the carters they could not get the cargo off the docks.

The 1907 dispute saw unprecedented working class unity on the streets of Belfast—a city known for its sectarian division between Catholic and Protestant. When attempts were made to shift cargo hundreds of Protestant shipyard workers reinforced the mainly Catholic picket lines. Eventually even the police mutinied and refused to continue to escort scab cart drivers. Troops were sent into Belfast and in fierce clashes two men were shot dead.

The strike was finally broken not by the employers or the army but by the intervention of the NUDL’s general secretary, James Sexton. Sexton convinced carters into returning to work with a pay rise. The dockers were isolated and doomed to defeat.

Larkin’s militant tactics had won the support of rank-and-file workers, but alarmed the conservative trade union leaders. Larkin was removed as organiser for the NUDL but he had already acted to form a new fighting union—the Irish Transport and General Workers Union.

Syndicalism

The ITGWU was informed by syndicalism, a form of revolutionary unionism that swept France, Spain, the US and Australia in the early years of the twentieth century. Its great strength was its commitment to militant unionism, through bold tactics and a willingness to take strike action.

Larkin saw the ITGWU as an effort to build “one big union” that would organise Irish workers across industry lines in a challenge to capitalism as whole.

His aim was to organise the entire Irish working class, in order to declare a general strike that would seize control of the workplaces from the employers and bring the working class to power.

James Connolly, the renowned Irish socialist and the ITGWU organiser in Belfast, shared Larkin’s syndicalist politics. During time spent in the US Connolly had become involved with the syndicalist Industrial Workers of the World.

Connolly recognised in the idea of industrial unionism the power, “to transform the dry detail work of trade union organisation into the constructive work of revolutionary Socialism”. For Connolly every fresh shop or factory organised under the banner of industrial unionism was, “a fort wrenched from the control of the capitalist class and manned with the soldiers of the revolution to be held by them for the workers.”

The ITGWU aimed to organise Ireland’s large unskilled workforce and it grew quickly from 4000 members in 1910 to 22,000 by 1912. Larkin’s militant tactics—solidarity strikes and the “blacking” of goods tainted by scab labour—earned significant improvements for Ireland’s most exploited workers. In so doing, however, the ITGWU raised the hackles of some of Ireland’s most powerful capitalists. William Martin Murphy, newspaper baron and Dublin United Tramways Company (DUTC) owner, one of Ireland’s richest men, was prominent among them.

The Lockout

In August 1913 Murphy demanded that workers in the dispatch office of his Irish Independent newspaper drop their ITGWU membership. Forty workers were immediately sacked for refusing to do so. Two days later he sacked 200 tram workers for the same reason.

By September the Employers Federation had joined Murphy in his battle against the ITGWU. Employers across Dublin initiated a general lockout of 25,000 workers to try and smash the union.

The Lockout of 1913 was bitterly fought. Trams that tried to operate during the lockout were attacked with stones by striking workers. In one such incident a scab tram driver drew a revolver to force his tram through against an angry crowd: William Martin Murphy had ensured that “loyal” employees had been issued with licenses for firearms.

Violence between workers and the police was rife. Larkin announced he would address an open air meeting in O’Connell St (Dublin’s main thoroughfare) on Sunday 31 August. The meeting was banned, but in defiance James Connolly, Larkin’s chief lieutenant during the dispute, suggested to a mass meeting that on the day people might choose to take a stroll down O’Connell Street to see if a meeting was being held there or not. For his suggestion Connolly was arrested for incitement.

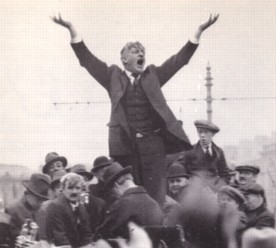

On the day of the banned meeting Larkin appeared on the balcony of the Imperial Hotel on O’Connell Street—an establishment owned by William Martin Murphy. As bystanders and sympathisers began to cheer the police attacked. A witness described them as, “the most brutal constabulary ever let loose on a peaceful assembly … kicking the victims when prostrate was a settled part of the police programme”.

This became known as “Bloody Sunday” (one of four in Irish history). Over that weekend police beat three working class men to death: John Byrne, James Nolan and James Carey. Police broke into people’s homes, ransacking them and assaulting residents. John McDonagh, who was paralysed and confined to his bed, was beaten so badly that he died later in hospital.

The Lockout was a life and death class struggle and there was no doubt as to which side the police were on.

Solidarity action

Larkin and Connolly understood that without solidarity action from unions in Britain to ban Irish goods the strike would be lost.

Many workers in Britain quite rightly recognised the attack on Irish workers as an attack on their own rights. Thousands of British railway workers stopped work in solidarity. Food ships sponsored by the British Trade Union Congress (TUC) steamed into Dublin port to feed the strikers and their families.

The militancy of the ITGWU was politically awkward for the British trade union leadership. They hoped to broker a negotiated settlement to the dispute, even if that meant capitulating to the Dublin employers. The employers, however, refused to compromise, demanding the complete destruction of the ITGWU.

In November Larkin travelled to Britain to build support for the strike, in what became known as the “Fiery Cross Crusade”. Larkin spoke to thousands of workers; at a meeting of 4000 people in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall (with some 20,000 more outside), Larkin declared that he was “out for revolution or nothing”.

British workers, he said, had “sent money and moral assistance” but now they had to help “get the scabs out of Dublin”. British workers were roused but their trade union leaders were alarmed.

The Trade Union Congress (TUC) called a special conference to discuss the Dublin dispute. It was stacked with conservative full-time union officials. Even worse, some union delegates known to be sympathetic to Larkin were denied accreditation.

The conference proceeded to censure Larkin for his attacks on the trade union leadership. The proposal for solidarity action through banning goods on rail and sea from Dublin was overwhelmingly defeated.

The conservatism of the full-time union officials, a product of their distinct position as mediators between capital and labour, saw defeat snatched from the jaws of victory.

In the aftermath Connolly commented acerbically: “the Dublin fight was sacrificed in the interests of sectional officialism … Irish workers must go down into Hell, bow our backs to the lash of the slave driver … and … eat the dust of defeat and betrayal. Dublin is isolated.”

By January Dublin workers were forced by deprivation to return to work. Connolly described the Lockout as “a drawn battle” but the ITGWU had been badly mauled during the dispute and it would take some years to rebuild the union’s capacity for industrial action.

The Dublin Lockout’s centenary is celebrated this year by the likes of the Irish nationalist party Sinn Féin. The Lockout was not, however, a nationalist struggle; it was a class struggle of Irish and British workers pitted against employers. William Martin Murphy himself identified as a nationalist and championed it in his newspaper.

This is part of the lesson of the Dublin Lockout. When populist millionaire politicians like Clive Palmer claim to be “uniting the nation” we should recall the nationalism of William Martin Murphy as he tried to starve Irish workers into submission.

The Dublin Lockout was defeated not because of the ITGWU’s militancy but because its actions were not supported by the more conciliatory trade union leaders of the British TUC. British and Irish workers were willing to fight, their leaders were not.

This problem is all too familiar in the union movement today. In 2013, with an Abbott government poised to launch its own attack on the living conditions of working people, we can learn from the courage and militancy shown by Irish workers.