The Sydney University strike campaign ended in June, with 80 per cent of union members voting to accept management’s offer, and 96.5 per cent of workers supporting the agreement in the final ballot.

The final result is a mixed bag. In the words of one worker, “I’ll be getting sick pay for the first time in my life, but the below inflation pay rise is going to be hard.”

The branch has a sector leading win on sick pay for casual staff, held back the attempt of management to rip the 40:40:20 academic workload allocation out of the enterprise agreement, made improvements on conversion rights, wage theft, working-from-home rights, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment targets.

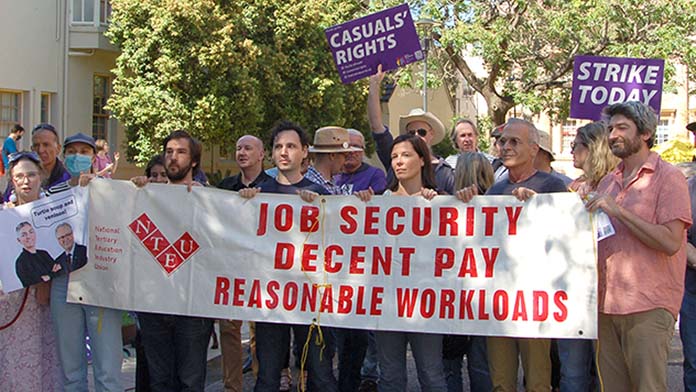

The branch’s epic struggle broke records for the National Tertiary Education Union with nine days of strike action, 22 months of negotiations and repeated member meetings of 700 to 900.

Management, however, has kept our pay rise below inflation and won a huge expansion of so-called “Education Focussed Roles”, a method of lumping academic staff with almost double teaching workloads.

Rank and File Action (RAFA), a rank and file grouping of union activists that has been crucial to building the strike campaign, argued to reject the deal and to continue the fight.

Three factors influenced the members’ decision to accept management’s deal: cost of living, industrial law, and the limits of the NTEU official strategy.

After just a 2.1 per cent increase over the prolonged negotiation period, workers were severely feeling the pinch.

Management pushed hard, insisting that the $2000 settlement bonus and the 4.6 per cent pay rise was contingent on a successful yes ballot.

Workers had already won an additional 1.5 per cent, bringing the pay offer to 16.1 per cent over four years. But to break the pay framework being set in the sector more strike action was needed, along with the possibility of united action with other campuses across the country.

Secondly, the anti-strike laws have been used to limit industrial action since day one. Marking bans were judged early to be unlawful and foolishly left off the protected action ballot, and stop work meetings had also been deemed unlawful after the union failed to implement the industrial action within 30 days of workers authorising it.

Albanese’s so-called “Secure Jobs Better Pay Act”, that became law in June, gave management the right to apply to the Fair Work Commission, after nine months of bargaining, to declare a dispute “intractable”. If granted, Fair Work can impose a new enterprise agreement, unilaterally set any non-agreed terms, and end the period of lawful strike action.

Though union officials rightly pointed out that these changes were an attack on the right to strike, they argued the only option was to settle with management quickly. There was never any strategy to challenge or defy the laws.

Officials’ strategy

Finally, the Sydney University struggle was politically isolated by the NTEU officials.

While division and federal officials were willing to encourage limited strike action, after one day (or sometimes less) of strike action, they pushed branches to settle.

Officials call this an “expedited bargaining” strategy, seeking to limit militancy, settle quickly, and accept weak management offers to avoid testing new IR laws, or any risk of non-union ballots.

Officials also kept USYD isolated by delaying any declaration of the national week of action. Coordinated national action could have boosted the fight at USYD, but the officials didn’t announce the week of action until the morning after the decisive 18 April meeting that voted against strike action.

The vote does not spell an end to the struggle at Sydney Uni.

The 42 per cent of the membership that voted to continue striking, and the 20 per cent who voted to reject the agreement entirely, indicate a strong base to fight any future management attacks.

The union will need to resist the expansion of Education Focussed Roles and fight on wage theft, hopefully with a renewed energy from the hundreds of workers mobilised throughout the campaign.

But there are sharp lessons for the NTEU across the country. The uncompromising nine-day strike campaign saw membership grow at a time of shrinking national net membership. Strong picket lines are an incredible weapon that can mobilise and cohere the struggle when confronting an intransigent management.

A militant and organised membership is needed to counter the limited framework of the union officials that will eventually confront every branch that moves into action.

Workers need to understand and prepare to fight the anti-strike laws, including breaking the taboos around illegal industrial action.

The struggle at Sydney Uni has set an example. The possibility of other branches winning better pay and conditions will depend on learning from the experience to build greater levels of militancy and an organised rank and file.

By Sophie Cotton, Branch Committee NTEU Sydney Uni