As we face vicious state Liberal governments, David Glanz looks back at the fight against vicious neo-liberal Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett twenty years ago and the strike movement that could have been his demise

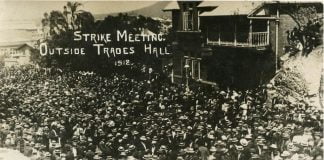

Twenty years ago, on November 10, 1992, the Victorian working class struck and came out on to the streets in numbers that shocked everyone, including union leaders, the media, the ruling class and workers themselves.

Perhaps 150,000 workers clogged central Melbourne. Tens of thousands also took to the streets across regional Victoria. Statewide, there were 800,000 on strike. The Victorian Trades Hall Council had called a rally in a city park, providing a modest PA system. No one heard the speeches. Most workers didn’t even get into the park.

The demonstration was the biggest in decades, mobilising far beyond traditionally militant unions in manufacturing, the waterfront and construction. Members of the shop assistants’ union marched to the park in considerable numbers. Journalists at Murdoch’s Herald Sun struck, as did federal and state public servants.

The mass strike, called by a Trades Hall mass meeting of 4000 delegates and shop stewards, was a response to a blizzard of attacks launched by Jeff Kennett, elected as Liberal Premier just a month earlier, on 3 October. According to the Herald Sun, Kennett’s government passed 34 bills in 12 sitting days:

- Dozens of government schools were closed immediately, with the final toll reaching more than 350, with the loss of 7,000 teaching jobs;

- New employment contracts were brought in, which outlawed penalty rates, leave loading and picket lines;

- Tens of thousands of public servants were sacked;

- Water, electricity and gas were privatised;

- Public transport came under attack, with tram conductors scrapped;

- The government imposed a $100 tax on households.

Kennett attacks

According to conventional wisdom, Kennett’s victory at the polls in October indicated a shift to the right in Victorian politics and a popular acceptance that something had to be done to curtail the state’s debt in the midst of the recession of the early 1990s.

In practice, his win was a result of a working class revolt against the austerity measures implemented by the previous Labor Premiers John Cain and Joan Kirner, which led to the axing of 31,000 jobs in three years and the sale of the State Bank of Victoria.

As the recession bit, Kirner put 2200 state government properties up for sale and contracted out services. Her government cut funding for community groups like the Public Tenants Union and the Aboriginal Advancement League. $105 million was cut from education in 1990 and $125 million the following year.

Workers were outraged with Kirner. Kennett, on the other hand, had a reputation as something of a buffoon. Too many people thought they could punish Labor by voting Liberal—after all, how could they be worse?

They were wrong. Kennett launched a blitzkrieg against the working class, gambling on battering people into quick submission. As he told The Age: “We were ready to govern. We seized that opportunity. We used that mandate.”

But Kennett in turn miscalculated. Rather than achieving a quick knockout win, his attacks provoked the return of the mass strike for the first time in two decades. Many in the ruling class panicked at the sight of 150,000 marching on parliament on November 10.

The nervousness was reflected in The Age the next day. “Yesterday’s strike and rally has energised and empowered his real opposition [the unions] in a way they could only have dreamt of … Mr Kennett should back off, and keep his eye on the substance of change rather than the form.”

But Kennett and his Treasurer, Alan Stockdale, were not buffoons. They were class warriors in the mould of Britain’s Margaret Thatcher. And they would not give way on the basis of even such an impressive strike.

Within days they had harangued The Age into a backflip. On November 17 it editorialised: “If it comes to the crunch … then the Government must prevail. There is room for further consultation and compromise on detail, but not on the essential thrust of the reform program.”

But for most workers, November 10 was the beginning of the fightback. There was a widespread appetite for further mass action. In communities, people began to organise—occupying schools in Richmond, Northland and Fitzroy that were slated to close in the December, protesting the planned closure of the Upfield and Williamstown rail lines.

The argument to many workers seemed straightforward: widen the strike action (including shutting down the power stations in the Latrobe Valley, which were exempted from the November 10 strike), and thereby cripple the new government.

Union strategy

The union leadership saw it differently. Trades Hall was led by secretary John Halfpenny, a former Communist Party metalworker, by then a member of the left of the ALP. He understood the need to make fiery speeches and commit to further mass rallies, to put himself at the head of the movement. But at the same time, he and other officials began reminding workers that it would be “a long fight”.

The immediate outcome was to undermine the ACTU’s national day of action against Kennett, on November 30. Workers in many parts of the country walked out on strike—in Brisbane, 5000 attended a mass meeting, with thousands more gathering in Rockhampton, Mackay and Townsville. It showed the potential for a national fightback and laid the basis for later mass strikes in Western Australia against the Liberal government of Richard Court.

But in Melbourne, there was no central rally. Strikers, including construction workers, metalworkers and public servants, marched separately, in some cases just city blocks apart. The unity and sense of power that workers had experienced on November 10 was beginning to be squandered.

The struggles drifted apart. Victorian public transport workers, wharfies, health workers, nurses, teachers and state public servants all took strike action. But the sense of one big fight was lacking. Trades Hall called off a strike in the power industry on December 9 and declared a “Christmas truce”.

Numbers at a mass delegates meeting in Melbourne in February dipped to 2000. As The Socialist, a forerunner of Solidarity, reported at the time: “The willingness to fight was still there. Not one delegate spoke against action … But the mood was sober.”

In a major warning sign, the tram workers’ union held a mass meeting on the same day and accepted a shoddy deal, trading away conductors’ jobs for minor concessions.

The Trades Hall delegates meeting did endorse a mass stoppage on March 1 and 80,000 marched. By “normal” standards, it was a magnificent turnout. But in the context of the previous November it represented a clear decline and everyone knew it.

There were no more mass rallies and, with Kennett looking powerful, even the sectional battles wound down. It was left to the occupiers of the three schools to carry the banner of struggle.

The legacy

Last month, Kennett told the Herald Sun that his government won by attacking on several fronts at once. “The beauty of that strategy was that after the initial flurry of protests from those who were most affected, everyone started protecting their own area of interest. So we split the opponents.”

But this outcome was far from inevitable. The key problem was the politics of the union leadership and the layer of worker activists who looked to them. As The Socialist put it in February 1993: “Why is the union leadership so half-hearted? … Part of the answer lies in the nature of the trade union bureaucracy …

“Their central concern is to retain their position as negotiators. As Halfpenny said at the delegates’ meeting, the fault with the Tramways Union was not talking to the Liberals but failing to consult Trades Hall about the deal.

“The other part of the answer lies in the officials’ belief that political change comes only through ALP governments. Behind the fighting rhetoric, the message from senior Victorian officials is that will take four years to beat Kennett—in other words, until the next state election. The union officials hold back the struggle because they think it cannot win.”

Halfpenny in later years said he regretted scaling down the campaign. But it was much too late. Kennett survived until 1999, doing enormous damage to working class living standards and services.

The strikes of 1992 and 1993 did not stop him, but they did have a lasting impact in two respects. One was a sharp shift to the left among union officialdom. Left or reform tickets won in unions including those covering electricians, textile workers, firefighters, foodworkers and metalworkers.

The other was to resurrect the practice of mass mobilisations and political strikes, particularly in Melbourne. The spontaneous walk-offs in support of East Timor in 1999, the S11 anti-capitalist protests of 2000, the massive march against war in Iraq in 2003 and the succession of huge rallies against the Workplace Relations Act and then WorkChoices owed a debt of gratitude to November 10, 1992.

Today, facing new rounds of attacks from Liberal state governments in Queensland, NSW and Victoria, we can draw two key lessons from 1992.

The first is the need to unite the separate struggles. When industrial resistance becomes general, it creates a political crisis for our rulers.

The second is to build a fighting socialist party that can provide an alternative political leadership within the workers’ movement when union officials fail to do the right thing.