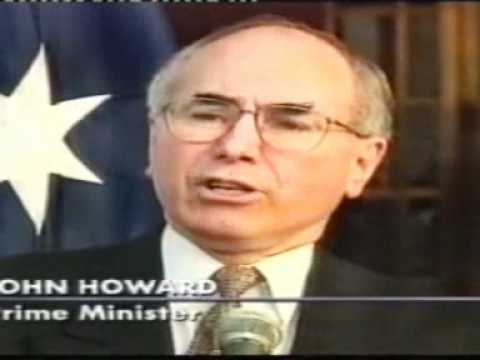

As Abbott takes the reins, James Supple looks at the mass anger against Howard’s cuts and racism that nearly toppled his government in its first term

John Howard’s election in March 1996 sparked a wave of protest that very nearly saw him driven from office after one term. The lesson is that if we fight, we can push the Coalition back and cut short Tony Abbott’s time as Prime Minister.

Much like this year, the Coalition were elected in 1996 on the back of intense anger at Labor after 13 years in power. Bob Hawke and Paul Keating had pushed through neo-liberal policies designed to cut wages in order to restore big business profits.

Howard hid his real agenda behind slogans like a promise to govern “for all of us”. Tony Abbott adopted the same strategy during his election campaign, refusing to outline what he stands for or the Coalition’s plans in office.

But almost immediately John Howard signalled new plans for sweeping anti-union laws and savage cuts to spending. The Coalition claimed they had found a huge “budget black hole” and used this to renege on what were branded “non-core” promises.

The government’s first budget included $5.8 billion of cuts in its first year and $9.8 billion the year after. They hacked $1.7 billion out of university funding, equivalent to 5 per cent of the higher education budget, with $800 million more saved through increasing HECS fees. In his first two years in office, Howard slashed 22,000 jobs in the public sector.

The Liberals’ Workplace Relations Act introduced individual contracts (AWAs), reduced conditions allowed in awards and sought to make strike action more difficult by imposing huge fines for “illegal” industrial action.

Fighting Howard’s cuts

This sparked a nation-wide campaign as public servants, unions and student groups mobilised against the Liberals. There were union mass meetings and marches against the industrial relations changes and job cuts in the public service. In Melbourne 50,000 workers marched on the Liberal Party headquarters in July.

University staff unions called a national strike against funding cuts, with rallies jointly backed by the National Union of Students. An estimated 7000 staff and students marched in Sydney, with 27,000 on the streets across the country.

The culmination of all this was a “cavalcade to Canberra” on the day before the budget in August 1996. The unions booked buses and trains to bring 25,000 protesters mostly from Sydney and Melbourne to march on parliament house. The AMWU’s NSW branch alone organised 47 buses.

The Liberals were isolated as public opinion turned against them. Polling suggested that 60 per cent were prepared to pay higher taxes to avoid cuts to health, education and welfare.

On Budget day, a poll in The Australian showed 63 per cent were opposed to increases to student fees through HECS and 67 per cent opposed cuts to university funding.

The ACTU and trade union leaders had a limited aim to seek to amend Howard’s anti-union laws and modify the cuts, instead of opposing them completely. They saw the purpose of the Canberra cavalcade as lobbying Democrats Senators to make amendments to Howard’s changes.

But the anger against Howard, combined with police provocation, meant that a huge section of the crowd surged past the official speakers’ stage and tried to storm parliament house. Protesters forced their way through one set of doors as they attempted to reach the parliamentary chamber.

In response to media hysteria about a “riot” the ACTU collapsed into condemning violence, allowing the issue of Howard’s attacks to disappear from discussion. Instead of building on the workers’ anger and escalating the fights against Howard, union leaders refused to call any further protests.

The result was that the Democrats in the Senate passed most of Howard’s cuts to universities and made only minor modifications to Howard’s Workplace Relations Act.

Howard also faced opposition to his racism and attacks on Aboriginal rights. He refused to apologise to the Stolen Generations and, in response to the Wik High Court decision, implemented his “ten point plan” to savagely restrict native title rights.

But by the middle of 1998 there were 260 grassroots reconciliation groups across the country.

From March 1998, hundreds of protesters travelled to the Jabiluka mine site in the Northern Territory to oppose uranium mining on Aboriginal land near Kakadu national park. Over 800 people were arrested during the eight month blockade.

Thousands also joined protests against Pauline Hanson, who was elected to parliament in the 1996 election. Howard welcomed her racist views by celebrating the fact that, under his government, people could now, “talk about certain things without living in fear of being branded as a bigot or as a racist”.

MUA dispute

Then in April 1998, the Liberals tried to break the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA). The docks were one of the bastions of trade unionism in Australia, with 100 per cent membership and serious industrial power. National strikes in 1993 and 1995 had shut down the ports nation-wide, paralysing the national economy with companies unable to bring goods in or out of the country.

The government conspired with Chris Corrigan and his stevedoring company Patrick to de-unionise its operations, sacking up to 2000 wharfies and replacing them with scab labour. But mass pickets at the docks effectively closed down Patrick’s terminals.

Victorian Police Minister Bill McGrath vowed to clear the picket at Melbourne’s East Swanston Dock, even if it took a bloodbath. More than 3000 people camped out overnight, defying court orders to leave. Hundreds of police began to move against the picket in the early hours of 18 April. But at 8am 2000 construction workers walked out on strike, marching on the police to reinforce the picket. The police lines collapsed.

The government was forced to concede that the picket would stay. But the ACTU had refused to sanction all out strike action to shut down the docks. When workers at the other major shipping company P&O in Sydney walked off the job in solidarity with MUA members at Patrick, they were ordered back to work.

The union leaders were running scared of the huge fines for “illegal” strike action Howard had imposed with his new Workplace Relations Act.

The ACTU strategy of relying on court action and refusing to defy Howard’s anti-strike laws prevented a decisive union victory. They had put their faith in a court case against Patrick’s illegal action in sacking workers because of their union membership. But the law only required Patrick to pay workers compensation, not give them back their jobs.

The mass pickets prevented Corrigan’s effort to break the union. But because the MUA agreed to a legal settlement it was forced to make enormous concessions. Six hundred workers were never reinstated and many conditions were lost.

Yet the MUA dispute was a serious political defeat for the Liberals, showing the degree of community support for trade unions and putting a stop to their plans for a frontal assault on the union movement.

Near death experience

As a result of the growth of opposition and the fightback on the streets, the Liberals plummeted in the polls. They fell from a 20-point lead on primary votes over Labor, shortly after Howard’s election, to trail Labor by 11 per cent by June 1998. Howard’s disapproval rating reached 57 per cent.

In desperation, Howard announced plans for a GST in an attempt to refocus the political debate in the lead up to the 1998 election.

Labor won a majority, 50.1 per cent, of the popular vote in 1998, but not a majority of seats. Although the Liberals lost 14 seats, they narrowly retained government.

The anger and opposition to Howard did force Labor to tack slightly to the left. Early on, Labor leader Kim Beazley had promised to be a “non-obstructive opposition”, and supported Howard’s introduction of work for the dole.

In the election campaign, however, Labor opposed the introduction of the GST and talked of reversing some of Howard’s cuts.

But instead of offering a clear alternative, Labor attempted to reassure business by promising to run budget surpluses in office. This meant it could not pledge to fully restore Howard’s funding cuts. Instead of promising to tax the rich and fund services it tried to match Howard’s promise of tax cuts with tax cuts of its own. It also refused to dump Howard’s native title changes.

Despite the MUA dispute happening only months before the election, Labor didn’t raise the issue during the campaign, and would not promise to fully repeal Howard’s Workplace Relations Act.

Howard could have been booted out in 1998, instead of having 11 years in power. What saved him was the efforts of Labor and senior union leaders to hold back the struggle at key points.

If we fight Tony Abbott, through strikes and demonstrations, building campaigns and social movements, we can expose what he really stands for and drive him from power.