Our of the last wave of Arab revolutions, Iraq developed the most powerful left in the region. Mark Gillepsie examines the lessons of that revolt for today’s upheavals

This year the repressive regimes across the Middle East have been challenged by a new wave of revolt. In Egypt and Tunisia pro-Western dictators have been toppled.

But these revolutions are far from finished. In Egypt the military has taken power in an attempt to hold together as much as Mubarak’s regime as possible, and to maintain his support for US imperialism and Israel. In countries like Syria the opposition has yet to mobilise a force capable of toppling the regime.

In Egypt, workers helped seal Mubarak’s demise. Since his removal, they have risen up in a strike wave across the country demanding fair wages and control of their workplaces. Millions have continued to protest in Tahrir square calling for a thorough cleansing of the old regime.

The new wave of Arab revolutions echoes the waves of struggle after WWII which brought down regimes imposed by then dominant Western imperial powers France and Britain. But it is the nationalist political regimes that emerged from these struggles that are today being challenged and overthrown.

Understanding what went wrong, and the failure of the nationalist and left-wing political currents that created them, requires revisiting that history.

One of the most powerful struggles was the revolution in Iraq in 1958, which gave birth to the largest and most powerful left in the Arab world. Iraqis united across ethnic, religious and tribal divisions and overthrew the brutal British backed Hashemite monarchy. Profound social and land reform followed.

At the centre of this revolution was the young Iraqi working class concentrated in Iraq’s rapidly growing urban centres. While the workers lacked the political organisation to take and hold power, and a new elite filled the vacuum, their struggle nonetheless shows the possibility for today’s revolutions.

The making of Iraq

The regime that ruled Iraq until the 1958 revolution was imposed by Western imperialist powers.

Iraq as a country did not exist until 1919. It was carved out of the collapsing Ottoman Empire by the powers that won the First World War. As Turkish troops retreated from the Middle East, Britain and France moved in to create a string of new colonies and client states.

Britain received the League of Nations’ (club of rich nations) mandate to rule Iraq—and control of its oil riches.

The British were never welcome. An uprising in 1920 was suppressed at a cost of 2000 British soldiers’ lives. It was during this uprising that chemical weapons were first used in the Middle East. Winston Churchill, the then British secretary of state in the war office, authorised their use against the Kurds and other “uncivilised tribes”.

The depth of resistance convinced the British to install a puppet regime headed by “king” Feisal I, the son of Hussein ibn Ali, the Grand Sharif of Mecca. Feisal was a complete interloper who had previously declared himself king of Syria.

Nasser and the 1958 revolution

The “oligarchy of racketeers”—as one British official dubbed the corrupt regime—came crashing down on July 14, 1958.

A nationalist revolution lead by General Abdul-Karim Qasim and the “Free Officers” movement removed the boy King Feisal II and ended British influence in Iraq.

Mass demonstrations on the evening of the coup blocked the streets and prevented any hostile

movement of troops. Iraq’s monarchy collapsed.

The revolution in Iraq was part of a regional upheaval against imperialist control inspired by the rise to power of President Nasser in Egypt and his successful defiance of the main Western powers in the region, Britain and France.

Nasser overthrew a British backed monarchy in 1952 and attempted to steer a course of genuine independence. Part of his strategy was to encourage national liberation struggles against colonialism and the formation a third block of developing nations between the rival superpower blocks of the US and the USSR.

The Western powers felt Nasser was a threat to their influence and needed to be brought into line. At first they flexed their economic power, denying Egypt loans it needed to build the Aswan dam, which was central to Nasser’s development program.

Nasser responded by nationalising the Suez Canal, telling the imperialist powers they could “choke in their rage”. This defiance was too much. Britain and France colluded with Israel to set up a provocation and invaded in October 1956. But this backfired.

The US, determined to displace the older colonial powers in the region, opposed the invasion and withdrew support for the struggling British sterling. The old colonial powers were forced into a humiliating retreat.

Millions of Arabs were inspired by this victory and Nasser’s picture decorated walls from Morocco to Aden to Palestinian refugee camps.

The grip of the imperialist powers on the region was shaken for a decade until the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, when Israel—now armed and funded principally by the US—smashed three Arab armies simultaneously.

Change from below

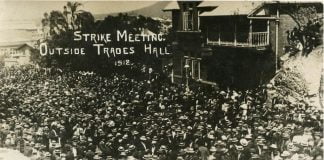

In the ten years leading up to the 1958 revolution, Iraq’s monarchy was repeatedly shaken to it roots by growing waves of workers’ strikes and protests.

In 1948 there was “Al Wathba” (the leap), a massive protest against the Portsmouth Agreement (essentially the renamed Anglo-Iraqi Treaty). Four hundred people were shot on the streets of Baghdad on January 27, but still the regime was forced to renounce the treaty.

On the heels of these demonstrations a great wave of strikes by rail, postal and oil workers rocked Iraq. Three thousand oil industry workers occupied the K3 pumping station during the strike; elected a strike committee; organised around the clock picketing; support from local villages; and later a 250 kilometre march to Baghdad.

“Al-Intifada” (the uprising) erupted in 1952. The masses came onto the streets to demand an end to the corrupt electoral system. The regime again responded with brutal repression declaring martial law, banning all political parties and ruling by decree.

By “Al-Thawa” (the revolution) in 1958, the monarchy was totally isolated. Historian Hanna Batatu describes the demonstration in Baghdad on the day the army officers removed King Feisal:

“Before very long the capital overflowed with people… many in a fighting mood and united by a single passion: ‘Death to the traitors and agents of imperialism!’

“It was like a tide coming in and at first engulfed and with vengeance Nuri’s [the prime minister] house and the royal palace, but soon extended to the British consulate and embassy and other places, and became so terrible and overwhelming in its sweep that the military revolutionaries, ill at ease, declared a curfew and the crowds ebbed back, the statue of Feisal, the symbol of monarchy, lay shattered, and the figure of General Maude, the conqueror of Baghdad, rested in the dust outside the burning British Chancellery.”

A dual power situation developed when workers in Baghdad, determined to prevent a counter-revolution by the old regime, began organising armed resistance cells.

Far reaching reforms followed the downfall of the monarchy. Unions were legalised, the eight hour day was established, rents were cut by 20 per cent, social insurance introduced, wages increased by as much as 50 per cent, the price of bread and flour cut while the new regime began construction of thousands of new homes. In the countryside substantial land redistribution broke the power of the tiny landowning elite.

These reforms survived even the rule of Saddam Hussein and only began to be seriously eroded in the 1990s as United Nations’ sanctions began strangling Iraq.

Whose revolution?

Iraqis were united in their opposition to the monarchy but after its collapse a new struggle broke out over the shape of the new Iraq.

On the one hand, there were the military officers that had initiated the 1958 revolution together with thousands of middle class professionals who had been part of the colonial state administration. But they aspired to “national economic development” not redistribution of wealth, let alone socialism. They wanted the huge fortunes being made from Iraqi oil to be directed toward developing the country’s economy along capitalist lines.

These middle class aspirations were enshrined in the constitution of the Ba’ath Party, formed in 1943. It called for the “cancellation” of concessions to foreign companies and the nationalisation of natural resources, banking, transport and utilities. At the same time, it also proclaimed “ownership and inheritance” to be a “natural right”.

Whereas the resistance to the British in 1920 was primarily tribal and rural based, by the 1940s and 1950s the urban working class had grown substantially and was leading the struggle.

Two factors were driving the urbanisation of Iraq. One was the limited industrialisation that came with the oil industry. By 1957 the oil industry alone employed 15,000 workers, but many more were concentrated in industries needed to support the oil industry—such as the railways, the port, and the post.

The other factor was the changing relations on the land. Old subsistence farming was replaced by capitalist land-holding. Agriculture became Iraq’s second export industry. But just 1 per cent of landowners owned 56 per cent of the land. Thousands of peasants were forced off their land, migrating to the cities looking for new opportunities.

But in the cities they came up against gross inequalities. Just 23 families owned 56 per cent of Iraq’s entire private wealth. Ninety two thousand people in Baghdad alone lived in sarifahs (mud huts) on the edge of town. Those lucky enough to find work found the conditions oppressive, their rights limited, and their survival constantly squeezed by the rampant inflation.

The concentration of workers in the big urban centres, however, allowed them to more effectively organise and cohere a movement. As most of Iraq’s key industries, such as oil, the railways and the ports were under foreign control, the young Iraqi working class found themselves at the centre of not only economic, but also nationalist agitation. A constant feature of their struggles was the mixing of demands for higher wages and better living conditions with nationalist demands.

“Al-Wathba”, in 1948, argues Hanna Batatu, was not just an uprising against British domination, but also “the social subsoil of Baghdad in revolt against hungry and unequal burdens”.

The Iraqi Communist Party

The most influential party amongst Iraq’s workers was the secular Iraqi Communist Party (ICP). It played an important role organising unions in oil, the railways and in the port. Effective union organisation began to break down ethnic, religious and tribal divisions. In Basrah’s port, for example, the ICP needed to overcome divisions between Nassar and Bahrakan tribes to organise a union.

The demands for reforms also cut across religious and ethnic divisions, polarising Iraqi society along class lines. So for example both Sunnis and Shias were united against a predominately Sunni regime in 1948, but in the process they also forced the resignation of Iraq’s first Shia Prime Minister, Salih Jabr.

By 1947, as an illegal underground party, the ICP had built a membership of 1800. Severe repression that included the public execution of its leaders reduced its membership to 500, but after the revolution it grew exponentially. At the peak of its influence in 1958/59 it had 25,000 members.

The party, however, had a severe political weakness. Influenced by Stalinism, it saw the struggle for socialism coming in stages. First was national liberation. The struggle for socialism was postponed to some unspecified later date. As we shall see, the potential existed to combine the struggle from national liberation with the struggle for socialism. But at crucial times the ICP held back the development of working class struggle.

Class divisions post 1958

The ICP saw their role limited to consolidating the nationalist revolution by working with the most “progressive” part of the new regime, which they identified as Qasim, the leader of the “Free Officers” movement.

As the party with the deepest roots amongst the masses, the ICP’s support for Qasim was crucial on numerous occasions for maintaining him in power.

In spite of the ICP’s loyalty, however, Qasim saw it as a threat to his power. During the mobilisations to defend the government the ICP was encouraging workers to arm themselves and patrol the streets.

Some workers even had the audacity to stop and search high-ranking military officers. Faiq as-Samarrai, a prominent diplomat, resigned his post, complaining that he’d been stopped and searched nine times in central Baghdad.

This frightened Qasim, who wanted to marginalise the ICP to reassure the upper classes, the foreign investors and the military elites, that he could be trusted to look after their interests.

A clash between Qasim and the ICP seemed inevitable. Britain rallied behind Qasim, providing him with arms to help put down a workers’ revolution.

But the revolution never came. A sharp debate in the ranks of ICP ended with it retreating and declaring loyalty to Qasim. Qasim rewarded the ICP by isolating and repressing them.

The politics of Stalinism, where the Communist parties were transformed from revolutionary organisations into mere instruments of Russian foreign policy, meant the ICP was not willing to seize this revolutionary moment. The consequence for the workers and the ICP was disastrous.

Many years later the ICP reassessed its actions, concluding it was a mistake not to challenge Qasim:

“We let slip through our fingers a historic opportunity and allowed a squandering of a unique revolutionary situation to the detriment of the people.. … Our party [had become] the master of the situation… and should of gone on to conquer power …even though civil war and foreign intervention appeared possible if not unavoidable… Had we seized the helm and without delay armed the masses in their interests, granted to the Kurds their autonomy and, by revolutionary measures, transformed the army into a democratic force, our regime would of have released great mass initiatives, enabling millions to make their own history.

The rise of the Ba’ath Party

Once Qasim had brought the mass movement under control, more conservative elements began to raise their heads. A right-wing coup removed Qasim in 1963 and brought the Ba’ath party to power. The Ba’ath Party butchered the ICP much more thoroughly, executing between 3000 and 5000 party members.

Saddam Hussein, who had been jailed for an earlier attempt on Qasim’s life, was freed and reinstated into a position of influence, from where he slowly established his personal dictatorship.

The US had no problem working with him when it suited their interests. A National Security Directive in 1983 stated the US would do “whatever was necessary and legal” to prevent Iraq from losing its war with Iran. Warm relations continued between the US and Iraq until 1990. Saddam Hussein fell out with his masters only after invading Kuwait—another pro-western regime.

The lessons for today

Today one of the dominant influences in the Middle East is political Islam, seen in the strength of groups like Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. But this is not an unbreakable influence. Political Islam was only able to build a following after the failure of secular politics, either in the form of radical Arab nationalism or Stalinism, to win genuine independence or show any way forward for the struggle to liberate the people of the Middle East.

Recognition of the central role the organised working class can play in a revolutionary movement, and its capacity to point the way to control of the region’s wealth by the mass of ordinary people, will be key in all the movements across the Middle East.

Rebuilding socialist organisation in order to bring together the fragmented workers’ strike movements in Egypt and ensure workers have their own independent voice in the revolutionary struggle is a critical task.

The efforts of revolutionary socialists in Egypt to build the Democratic Workers Party alongside independent unions represent key steps in this process.

In pushing forward the revolutionary process, the lessons of the last revolutionary wave in Iraq and across the region are an important guide in how to avoid the mistakes of the past.

Further reading

Hanna Batatu, The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq (1978).

Tariq Ali, Bush In Babylon: The Recolonisation of Iraq (2003).

Anne Alexander, “Daring for victory: Iraq in revolution 1946-1959” in International Socialism 99 (2003).

Tony Cliff, Deflected Permanent Revolution (1963).