The number of strike days between April and June increased sharply, with 73,700 workers on strike for a total of 128,100 working days “lost”—the highest number of strike days since 2004.

Over the year to the end of June, there were 154 disputes, 54 more than in the previous year.

In total, there were 234,600 strike days, 176,900 more than the previous year.

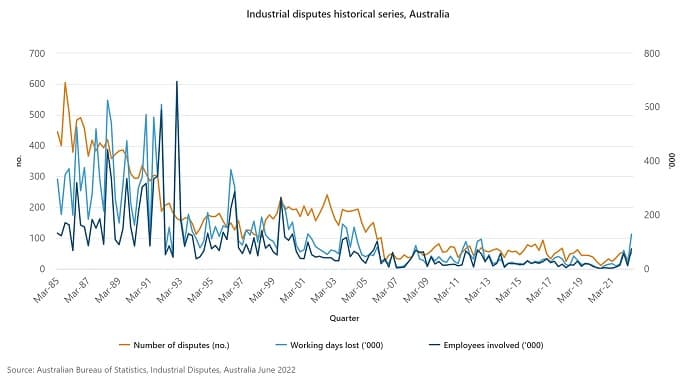

The increase comes off a low base—strike figures have been meagre since the introduction of anti-strike laws and enterprise bargaining by Labor in the early 1990s (see graph).

But it’s an indication that rising inflation is pushing more workers to fight back.

The end of COVID-19 lockdowns has also opened the way for unions to move on a backlog of deals as well as making it easier to organise for many workers previously working from home.

The bulk of the strike days (91 per cent) were racked up by education and health workers, with a major factor being mass strikes by nurses, teachers and public servants in NSW revolting against a 3 per cent wage cap.

University of Sydney labour law professor Shae McCrystal told the Financial Review: “What we’re seeing there is the impact of public sector wage policies from state governments, which systemically suppressed wages to the extent they’ve all had enough, and the chronic understaffing through the pandemic.

“Is anyone surprised at a time when these frontline workers have copped years of difficulty that they’re doing the only thing within their power to challenge their conditions?”

The fightback hasn’t stopped. Since the end of June there’s been a public service strike in WA, a nationwide walk-out by early educators, rail stoppages in Sydney and another 24-hour strike by NSW nurses. NTEU members are taking action across a number of NSW and Queensland campuses.

Anger is bubbling in Tasmania, too. The ABC reported: “The list of public servants taking strike action seems to be swelling by the day and encompasses some of the state’s most crucial front-line workers: teachers, paramedics, nurses, child protection officers and firefighters.”

The big exception is Victoria, where union officials with a close relationship to the Andrews Labor government have overseen derisory increases.

The Australian Education Union rammed through a 1.7 per cent agreement for teachers in March, when inflation was already at 3.5 per cent. There was unprecedented pushback from members, with 39 per cent rejecting the deal.

Now the rank-and-file group MESEJ is campaigning for the union to fight for an additional rise.

Mixed picture

Strikes in the private sector have been fewer but there are some encouraging signs there, too. At Lactalis in Perth, workers finally got rid of a “zombie” deal and won 12 per cent over two years, plus a raft of improvements to penalty rates and so on.

Airport baggage handlers employed by dnata have taken advantage of extreme staffing shortages to win 12 per cent upfront and 4.5 per cent next year.

Member of the manufacturing union AMWU at Crown Equipment in Victoria and Tasmania won 13.5 per cent over three years, frontloaded with an inflation-busting 7.6 per cent. Also in Victoria, AMWU members have won strikes at two Downer sites, although the win on pay fell just short of inflation.

But the picture is mixed, with big contingents of workers continuing to fall behind. At Telstra, a new agreement concedes just 2.5 per cent now and 3 per cent next year.

The MEAA has just settled for 4 per cent and 3.5 per cent next year at Nine Publishing.

Private sector wages rose in the June quarter by the highest seasonally adjusted rate since September 2013, but the average increase still amounted to just 2.7 per cent on an annual basis.

This is not surprising given the low level of struggle that has characterised the workers’ movement for a generation.

Recovery is unlikely to be immediate and it will be uneven. But inflation is creating pressures that can crack open business as usual.

Workers need to be arguing for a serious fight for wage outcomes higher than inflation and shorter deals to avoid being locked into future wage cuts.

Union officials are under some pressure—the NSW nurses’ vote to stick with their 7 per cent claim despite the union’s backsliding is a sign of growing discontent from below.

That pressure can result in more mobilisations, which in turn raise workers’ confidence and give them the experience of taking action that has been missing for so long.

The latest strike figures are promising. Now the task is to widen and deepen that spirit of resistance.

By David Glanz