James Supple looks at the lessons from the historic union defeat at SEQEB in 1985, when Joh Bjelke-Petersen took on the unions and won

Unions today face vicious laws, with massive fines imposed for unlawful strikes and effective picketing. Labor has imposed Administration on the CFMEU for its record of effective industrial action and history of defying the law.

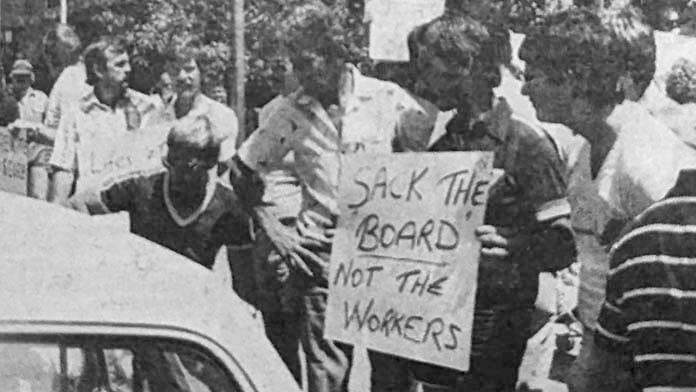

The 1985 SEQEB dispute, when 1007 electricity linesmen were sacked by Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, was a heroic struggle, fought from below not just against a conservative government but a state and federal union leadership unwilling to call the industrial action needed to win.

Their betrayal of the workers’ willingness to fight was a key turning point in weakening union power.

When Bjelke-Petersen sacked the workers, he had already prepared the ground. Coal had been stockpiled at power stations and power station operators had been progressively shifted out of unions like the electricians’ union, the ETU, into professional associations.

The ETU had been a thorn in the side of the Bjelke-Petersen government. Action by power workers had been key to a general strike that had forced Bjelke-Petersen to drop the use of the Essential Services Act against workers fighting for a 38-hour week in 1982.

Internationally all eyes were on the British miners’ heroic struggle against the Thatcher government’s pit closures, as conservative governments everywhere used state power to weaken unions. Now the struggle was in Queensland.

The sackings sparked a full-blown confrontation with the National Party government. Solidarity action from power station operators caused ten days of blackouts that saw 17,500 homes without power each night and cost business about $1 billion.

Coal miners in central and north Queensland declared an indefinite strike, followed by building workers. Maritime workers banned oil supplies, hundreds of railway electricians went out and unions imposed bans on phone repairs and transport to government departments.

Lift maintenance workers at parliament house stopped work, forcing the Premier to walk up many flights of stairs. Even the liquor supply to government ministers was cut off.

More than a million workers in Queensland were either on strike or stood down due to power cuts. Bjelke-Petersen admitted the dispute had “spread to the point where they can cripple the government”.

Yet the strike ended in a disastrous defeat as union officials rushed to compromise.

Iron fist

Bjelke-Petersen ruled Queensland with an iron fist from 1968 until 1987. An electoral gerrymander helped keep Labor out of office.

In 1977 Bjelke-Petersen banned street marches, triggering a defiant campaign for the right to march that led to thousands of arrests, before he was forced to back down.

The unions had previously faced him down and won. Power workers in the ETU staged a 48-hour strike in 1980 and won reduced working hours.

In 1982, when the government reneged on delivering a 38-hour week for public sector workers, it triggered a general strike. After the normally timid Australian Workers Union held a public sector stopwork, Bjelke-Petersen declared war, imposing a state of emergency.

The unions responded with a 24-hour strike. Mass meetings in Townsville, Mackay and Ipswich voted to go out for 48 hours instead. The government escalated the dispute, suspending 3500 railway workers and moving to deregister 11 unions. Strike action spread as rank-and-file workers took the initiative across the state.

After a week Bjelke-Petersen capitulated, dropping the suspensions and de-registrations and ending the state of emergency.

But the strike ended without securing the 38-hour week. Bjelke-Petersen had survived—but the ruthless measures he was willing to take to break union power were clear.

SEQEB dispute

“The SEQEB dispute was about the use of contractors,” replacing permanent jobs on standard wages and conditions, Dick Williams, former Secretary of the ETU in Queensland and an organiser at the time, recalled.

“A SEQEB document fell off the back of a truck and clearly stated that they were going to contract out all new line work.” The government aimed to cut the permanent workforce by 10 per cent.

On 6 February 1985, the ETU called an indefinite strike. When 1000 electricity linesmen defied a return-to-work order, Bjelke-Petersen declared another state of emergency and sacked them, announcing individual $1000 fines as well as the loss of all entitlements including superannuation. It was war.

The unions responded with power cuts and a wave of action that brought the government to the brink of defeat. But the Queensland Trades and Labor Council (TLC) told the power station operators to end the power cuts after the Premier supposedly promised to reinstate the linesmen.

The next day the government reneged. Worse, it demanded that workers reapply for their jobs and accept longer hours, brutal cuts to conditions and a no-strike clause.

But the union leaders refused to call workers back out. They had been spooked after Bjelke-Petersen began legal action against the power workers and the ETU for staging an illegal secondary boycott.

Instead they put their hopes in legal action. Bjelke-Petersen ended that option by passing legislation to remove access to the court for SEQEB workers. But the fight was far from over.

The sacked workers held a mass meeting demanding the TLC call a 24-hour general strike. They stormed the TLC Secretary’s media conference, accusing him of betrayal. Coal miners stayed out on strike for three weeks and railway electricians remained on strike.

The sacked SEQEB workers set up a rank-and-file strike committee and began picketing SEQEB depots, leading to at least 200 arrests, including Labor Party figures such as Senator George Georges.

But Bjelke-Petersen was out for blood. He imposed a series of extreme new anti-union laws making strikes and pickets across the power industry illegal, introducing $1000 fines and the threat of dismissal for refusing to follow the Electricity Commissioner’s directions. Deregistration of unions was made easier and secondary boycotts in solidarity with other workers became illegal.

However, the pressure for action pushed the ACTU into announcing a national blockade of Queensland in May. Freight deliveries were blocked for days at a time. But the ACTU gave Bjelke-Petersen a week’s notice of the action, making it less effective. And it was never intended to lead to the all-out strike needed to win.

Instead the ACTU called off the blockade after Bob Hawke’s federal Labor government agreed to allow the Arbitration Commission to consider shifting power workers onto a federal Award. It was a hopeless gesture, supposedly to get around Bjelke-Petersen’s attacks on conditions in the industry.

The sacked workers were totally sold out. Labor pathetically claimed, “There is absolutely nothing we could do … The Arbitration Commission can’t directly order reinstatement.”

Even this wasn’t the end. Pressure from the sacked workers and other unionists forced the TLC to call another mass stopwork meeting. On 20 August 260,000 workers across Queensland went on strike. But the union leadership had no intention of calling any further action.

The SEQEB workers battled on for two years—but never got their jobs back. Bjelke-Petersen bragged, “We have got the formula now to deal with the unions.”

Union officials

The failure of union leaders in the TLC and ACTU to deliver the solidarity action that could have defeated Bjelke-Petersen left the sacked workers, and supporters, extremely bitter. Ray Dempsey the then-secretary of the TLC was openly condemned as a “sell-out”.

Bernie Neville, one of the leading sacked SEQEB workers, told a protest outside the ACTU conference in Sydney on 9 September 1985, “The lights were off for ten days. We were close to victory. We were so close to a victory that would have meant the end of that bastard Petersen.

“But the TLC under the Secretary Ray Dempsey folded and turned on the lights. The decision to retreat and turn on the lights had the backing of every union official (left and right) in Brisbane … Yet the truth is that when the lights were turned on, we the striking workers were betrayed and sold out.”

Why did the union leaders leave the SEQEB workers to fight alone? Time and again union members showed they were willing to fight, with widespread solidarity strikes. Yet union officials continually called off action. They were desperate to avoid the all-out confrontation with Bjelke-Petersen that was the only way to win.

Union officials’ role as professional negotiators between workers and bosses leads them to seek compromise. Just as we have seen with the legal challenge to the Administration of the CFMEU, the officials favour working within the law.

Officials’ jobs and influence depend on the union’s assets and its bureaucratic machine. Bjelke-Petersen’s anti-union laws, which threatened large fines and union deregistration, made them draw back.

There were further factors at the time. A serious recession in 1982 had seen unemployment rise. It made workers less confident in their economic power.

This made union leaders even more willing to collaborate with government and the bosses. They had already agreed to prevent strike action and accept wage cuts under the Accords negotiated with the federal Labor government in 1983. Channelling Bjelke-Petersen, the Hawke Labor government ruthlessly smashed the Builders Labourers Federation in 1986 when they refused to go along with the Accord.

Going beyond the limitations of the officials requires rank-and-file workers organising independently. The SEQEB strike committee and the women’s committee set up by the sacked SEQEB workers showed the way. But without a rank-and-file network right across the electricity industry with links to other unions they were unable to organise the necessary statewide strike action.

There are lessons here for the fight against Administration of the CFMEU. The law is a straitjacket to constraint working class struggle.

Workers’ industrial power is the only way to win. Relying on full-time union officials working under the Administration, like the Victorian branch Executive Officer Zach Smith, is a dead end.

It was the strike committee and determination of the rank-and-file that kept the fight alive for two years. Forty years later, it is going to take similar organisation and determination to beat Labor and the bosses and win back control of the CFMEU.