A historic strike by Aboriginal workers in Western Australia 75 years ago against brutal oppression and forced labour won dignity and improved conditions writes Paddy Gibson

This year marks the 75th anniversary of a historic strike of Aboriginal pastoral workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, which began on 1 May, International Workers’ Day, in 1946.

The strike was a profound act of self-emancipation, winning significant freedoms for Marrngu (local Aboriginal people), who had been held in bondage on stations for decades suffering extreme exploitation, poverty and violence.

The colonial invasion of the Pilbara began in the late 19th century, unleashing genocidal violence on Aboriginal people. In the far north of WA, police massacres continued into the 1920s.

By World War Two, a series of huge stations were well established in the Pilbara, stocked with two million sheep over an area the size of Great Britain.

Wealthy pastoralists ran the region as a virtual dictatorship over Marrngu, whose labour provided the backbone of the industry. Marrngu were rarely paid cash and those that were paid received well below award wages.

Police were the local enforcers of the Native Administration Act that compelled Marrngu to stay on particular stations. Bashings, neck chains and exile were all used against Marrngu who stepped out of line.

A Royal Commission into the pastoral industry in 1944 made the crucial importance of Black exploitation plain when it argued: “There is an advantage in native labour … they are not sufficiently advanced to appreciate white conditions.”

In reality, Marrngu were acutely aware of how badly they were being exploited and, by 1944, preparations were already beginning for a strike.

‘McLeod gave us a hint’

A key character in the strike was Don McLeod, a white prospector who had been radicalised during the war when he joined the Anti-Fascist League in Port Hedland, which had both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal members.

McLeod became close with the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) and also began to speak with Aboriginal people he met while working on stations about the terrible conditions.

McLeod argued that the reliance of Pilbara stations on Aboriginal labour made them particularly vulnerable to a strike. Clancy McKenna, a key Aboriginal organiser of the strike, said these conversations provided an important strategic orientation for Marrngu, who had been discussing the need to challenge their conditions for many years. “McLeod gave us a hint about the strike and we took it up.”

Sometime during the war a major meeting was held far from the reach of police, at Skull Springs, to plan for a strike. McLeod described this meeting as a “mini United Nations”, with speakers from 23 Aboriginal language groups.

This meeting was an example of the way Marrngu kinship networks and patterns of ceremonial life fused with collective workers’ action during the strike.

The pastoralists’ paternalistic contempt for Aboriginal people led to a fatal under-estimation of the Marrngu. As pastoralist Edith Miller reflected: “We had always said that they could never be conscripted or get together in a crowd … we were wrong.”

At Skull Springs, McKenna and Dooley Bin Bin were elected as the main strike leaders. Along with demanding proper pay and freedom to leave stations, a key demand was for Don McLeod to be recognised as a representative of Marrngu in negotiations with pastoralists and the government.

During April 1946, Marrngu on a number of stations started striking early, taking advantage of the pressing need for their labour during shearing season. On some stations, wage increases were granted immediately.

On 1 May the action generalised, with 800 Marrngu refusing work on stations. There was also a widespread strike of Aboriginal workers in shops and industry in Port Hedland and Marble Bar.

On 3 May, Bray, the Commissioner of Native Affairs, telegrammed: “Native labour situation now very disturbed because of McLeod’s anti-fascist communistic activities … press for full term imprisonment.”

McLeod, McKenna and Dooley were arrested under the Native Administration Act, which made it illegal to encourage Aboriginal workers to leave their employer and for whites to congregate with Aboriginal people. In the towns, threats of arrest forced people back to work and on the stations a mix of concessions and repression disoriented the campaign.

In Perth, news of the strike was ignored by the mainstream press, which was controlled by pastoralists. The CPA newspaper Workers Star, however, carried detailed accounts of the action sent by McLeod.

These reports inspired a demonstration on 19 May calling for freedom for the arrested strikers and then a mass meeting on 28 May that formed a Committee for the Defence of Native Rights (CDNR).

The CDNR united communists and other union militants with local Nyoongar people, feminists, humanitarians and left-wing clergy. They began to raise significant funds for legal defence and agitated for resolutions of protest, which began to be sent to WA political leaders from a broad range of organisations.

McLeod was granted bail and travelled to Perth to build solidarity with the continuing strike.

On 25 June, McKenna and Dooley were released early, too, with the Workers Star arguing: “This is a direct result of the pressure of the unions and the people, roused to anger by the injustice of the arrests and violation of the fundamental right of every worker to organise to better his condition.”

Defiance

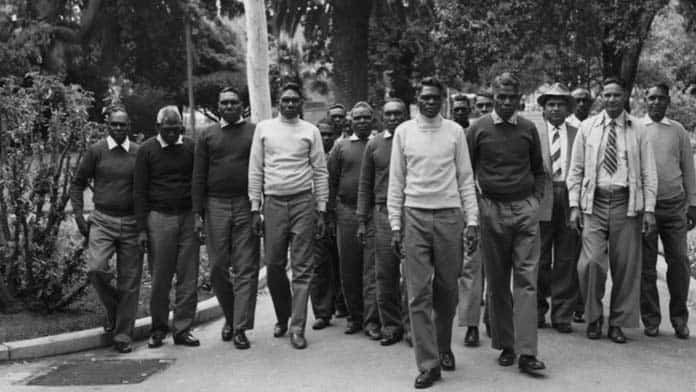

With their imprisoned leaders now free, the strikers regrouped at the Port Hedland race meeting in July 1946, a major event that brought people together from across the far-flung stations.

Hundreds of Marrngu established a camp at “Two Mile”, on the outskirts of Port Hedland, against explicit instructions from police that they camp outside the town limits. When police attempted to make arrests, people surrounded any threatened striker. Unable to break up the camp, police instead arrested McLeod once again.

Marrngu marched to the Port Hedland police station demanding McLeod’s release. This protest was an unprecedented expression of Aboriginal collective power in the segregated town, where shops immediately closed in fear.

In the wake of the Port Hedland race meeting, Marrngu established two major strike camps and subsisted by hunting, harvesting pearl shell and animal skins and small-scale mining. They made periodic moves to pull more Aboriginal workers off stations at strategic times in the shearing season.

The fact that Marrngu had proved capable of spreading their strike and hitting station profits provided a check on police powers. The hated practice of forced removal of children, for example, which continued apace across WA in this period, ceased in the Pilbara once the strike began.

Workers’ solidarity

Soildarity from the broader labour movement was crucial. The CDNR kept unionists across Australia updated on developments in the Pilbara and there was a constant stream of protest resolutions and donations.

In the Pilbara itself, despite the Native Administration Act imposing segregation, the co-operation of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal workers was required to keep the wheels of the pastoral economy turning and this provided a basis for solidarity.

At key moments in the strike, multi-racial working-class action that recognised pastoralists and police as the enemy of organised labour challenged the racist white Australian nationalism relied upon by the pastoralists to maintain their system.

The right-wing leadership of the Australian Workers Union (AWU) was deeply racist, but the Port Hedland AWU branch declared support for the strike almost immediately. Railway workers, both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal, defied attempts by the railway authorities to impose a ban on Marrngu strikers riding the rail.

In 1947, AWU members working at Port Hedland wharf resolved to strike to demand an end to racist regulations that stopped Marrngu from taking vacant wharf jobs. Although this decision was eventually overturned by the AWU leadership, it was solidarity from maritime unions in 1949 that eventually forced the major concessions that ended the strike.

Early in 1949, Marrngu began appealing for workers remaining on the stations to join the strike camps before the start of the shearing season. Police arrested 46 strikers.

In response, the WA branch of the Seamen’s Union of Australia (SUA), led by communist Rod Hurd, threatened to ban shipments of wool from Port Hedland. Some strikers were acquitted almost immediately. But the SUA insisted that key demands of the strikers were met before they lifted the ban.

Despite official AWU opposition, AWU members at Port Hedland refused to load wool.

Faced with a paralysis of the lucrative wool trade, a Department of Native Affairs official, Elliot-Smith, was forced to negotiate a settlement with McLeod which granted most major Marrngu demands.

After the wool ban was lifted, Native Affairs reneged on the deal. But the system of Aboriginal workers being bonded to stations was over and so was the official strike. Native Affairs recognised the rights of workers to contracts with individual pastoralists and to move freely between stations.

Large numbers of Marrngu never returned to work on the stations. They established mining co-operatives and managed to save enough money to buy back stations outright.

Their actions were an inspiration for Aboriginal activists and their supporters across Australia, laying foundations for demands for self-determination and return of lands that would become increasingly prominent in coming decades.

The Pilbara strike took extraordinary courage from Marrngu workers and their families, who faced intense colonial violence and oppression. The strike shows clearly that working class power and organised defiance of the law can effectively break a racist regime, a crucial lesson for all struggles for justice.