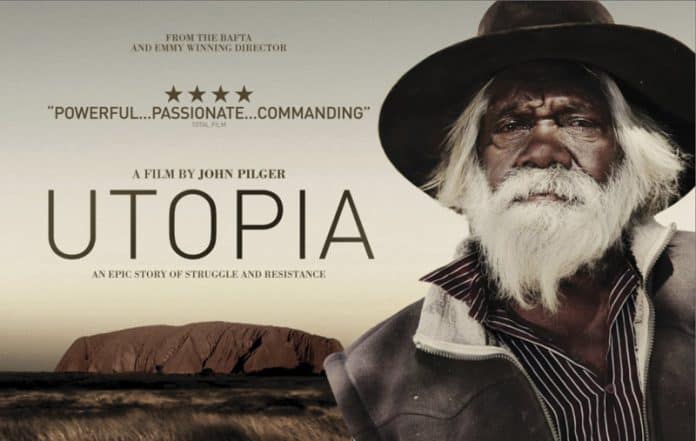

John Pilger’s new film Utopia exposes the worsening conditions for Aboriginal people as a product of the return to assimilationist policies, writes Lucy Honan

If you want to know what the Intervention has done to resuscitate assimilation politics and take the struggle for Aboriginal rights back decades, watch John Pilger’s Utopia. Against all the platitudes (amplified for Invasion Day) that pretend the horrors are in the past, and that “the first Australians” are a benign thread in a harmonious Australian national story, Pilger insists on the truth. Six years of Intervention politics are the sharp edge of disastrous poverty, criminalised Aboriginality and reignited Stolen Generations policies. This documentary is a storm of justifiable rage and an irrefutable argument for a fight back.

Assimilation politics resuscitated

“Those that have been assimilated into earning a good living, earning wages, accepted into civilised society… can handle society, I’d leave them well alone. The others—I would dope the water up so that they were sterile and would breed themselves out in the future, and that would solve the problem.”

Lang Hancock (Gina Rinehart’s father) offered this disgusting prescription for Aboriginal people in 1984. It opens the documentary because Hancock’s sick dream is playing out in 2013. Instead of sterilisation, successive governments have been starving out those Aboriginal communities that will not submit to the market economy.

Through the NT Intervention, Liberal and Labor governments axed thousands of community development jobs, cut off the meagre housing and services for the majority of remote communities in the NT, and introduced welfare quarantining, putting half their payments for “prescribed” Aboriginal people on a “BasicsCard”. Then the Labor government extended the measures to communities across Australia.

Pilger pulls no punches in showing the ongoing devastation in the NT: 30 plus people crammed into each asbestos filled house, third world diseases and mortality rates, dilapidated health clinics with blocked toilets, no public transportation, no access to decent nutrition, no running water. The situation is far bleaker than Pilger’s 1985 documentary A Secret Country, where communities were poor, but winning some control over land, radio stations, school curriculum and local councils. But even as they were won, all of those meagre victories for Aboriginal control were starved of funding and support and finally snuffed with the Intervention—bilingual education programs were banned, land compulsorily acquired, local social programs junked.

In one scene, Salil Shetty, General Secretary of Amnesty International, mentally calculates how easy it would be for a country as rich as Australia to just fund public services and put an end to the disgraceful poverty—in the midst of such wealth he cannot fathom the cause of the neglect. The deliberate nature of the neglect is illustrated where an Aboriginal man living in a shack with no kitchen or running water looks across at the 17 air conditioning units cooling a white bureaucrat’s house next door. The inequality is palpable.

Pilger puts the question to Warren Snowden, Indigenous health minister and MP for the most disadvantaged Aboriginal communities in Australia for nearly three decades: “Why haven’t you fixed it?” Snowden squirms in his own repulsive incompetence, which is delicious to watch, but it’s Rosalie Kunoth Monks from Utopia who gets to the heart of it: “they are starving us out”.

The federal government declared Aboriginal communities like Utopia unviable and cut them off from social spending, not because they are actually unaffordable—the territory is awash with cash for white bureaucrats and elaborate programs of social control—but because they had to be made to fit an Australian society where neo-liberalism reigns. It is now a six year long project to enforce values of individualism, mainstream economic participation and asset accumulation. As Abbott put it menacingly, “there is no place outside the mainstream” for Aboriginal people.

Abbott turned the pitch of the neo-liberal assimilation agenda up a notch further when he appointed a team of corporate bigwigs including Gail Kelly from Westpac and David Peever from Rio Tinto to advise on “economic Aboriginal reform” in November. His spokesperson echoed Hancock’s maxim that Aborigines need to submit to the labour market and corporate Australia’s rule: “we must ensure that children go to school, adults go to work and that the ordinary law of the land operates in Aboriginal communities.” Or else.

Criminalised

But the new assimilators are so patently not succeeding at their own mission.

Cutting Aboriginal programs like the Community Development Employment Program (CDEP) was supposed to force people into “real” jobs, wherever they existed. But Indigenous unemployment went from 15.6 per cent to 17.1 per cent between 2006 and 2011. Axing bilingual programs and cutting welfare payments for truancy was supposed to set a high standard of education. But Aboriginal children’s school attendance is plummeting across the country and markedly in the NT. It’s an admission of failure that Indigenous Affairs minister Nigel Scullion is sending an “army of truancy officers” into remote communities to try to persuade children back to school, while the Country Liberal NT government continues its cuts to remote schools.

Cutting Aboriginal services, Aboriginal jobs, and Aboriginal curriculum and piling on the punishments has not driven people into jobs that don’t exist. But it has driven people further into the margins of society, and into prisons.

Pilger reminds us that jailing Aboriginal people and killing them in prison is an Australian tradition—from the prison and execution site at Rottnest island WA, to the jails and police cells that kill young Aboriginal people like Eddie Murray in NSW, to Mr Ward’s cooking to death in the back of a police van in 2008, to the police who killed Kwementyaye Briscoe in 2012.

But with the Intervention and its extension across Australia, never have Aboriginal incarceration rates been higher. With it came 18 new police stations in the NT, star chamber powers for police and outrageously discriminatory penalties for carrying alcohol and porn in prescribed communities. No pedophile rings were caught, but many more people are locked up for traffic offences—largely due to poverty induced dependence on unregistered cars and unlicensed drivers. The former Minister for Corrective Services Margaret Quirk tells Pilger WA has begun “racking and stacking” prisoners to accommodate their numbers—piling them on top of each other in overcrowded cells. Now the WA government is building new prisons just for Aboriginal people.

Pilger uses footage of a police officer spray-and-wiping Briscoe’s blood off the floor after slamming him to the ground, knocking him unconscious, and dumping him face down to suffocate to death. She complains to a fellow officer that theirs is “not a glamorous job”. Her mundane murder is the threat lurking behind the Intervention, the brutal end point of Abbott’s “no room outside the mainstream” agenda.

Stealing children

The resurrection of mass child removals is the loudest siren in Utopia, warning us how far back into the dark ages of failed assimilation politics Australia has plunged. The numbers of Aboriginal children being removed are higher than they were at any point last century. In the NT the removal rates are double what they were before the Intervention, and across the country removal is overwhelmingly for “neglect”, a by-product of poverty and extreme disadvantage.

Pilger interviews Olga Havnen, who was Coordinator General for Remote Services in the NT until her scathing report earned her the sack. Where in one year the NT government spent only $500,000 to support impoverished families, they spent $80 million on surveillance of families and child removal. This spells the beginning of a new Stolen Generation.

There is a painful interview with Kevin Rudd, who is smarmy and defends his apology to the first Stolen Generation as not just “gesture politics”. But it’s clear, particularly in light of the new child removals how the apology served as a false bookend, pretending to close off an era of hostility while actually opening the frontiers to launch new attacks.

The apology and the Intervention politics are building up a mythology that the “Aboriginal Problem” is an historical one, and that there is no need for a struggle for a separate Aboriginal self-determination, that there is no conflict between Aboriginality and Australian nationalism.

Pilger’s Australia Day vox pops reveal the level of delusion. When Australian flag laden revellers are asked if they can understand why some Aboriginal people might be uncomfortable or angry with the celebrations, the responders are bemused, “Really? Why’s that?”, and “but we all think of them too now”, “but now it’s everyone’s place, we’re all Australians now”.

Throughout the documentary you get the sense Pilger just wants to shake “White Australia” out of its torpor. How can we not see how deeply Australian racism runs? How can we not see through the feckless politicians and their empty apologies, promises and lies?

Resistance

The documentary shows the depth of rage in Aboriginal communities, and the consistency with which Aboriginal people throw up resistance against each injustice. From the Gurindji who fought for land rights and sparked the shift toward self-determination in the 60s, to the Murrays who fought black deaths in custody for decades, to the people of Ampilatwatja who walked off in protest against the Intervention, to the women of Lightning Ridge who fought for their children back.

But Pilger’s solution at the end of the film is for a treaty between “White Australia” and “The First Australians”, rings hollow. The idea is not explored in any depth in the film, just dropped in at the end, seemingly as a silver bullet to cure all the horrors that have been shown. The usefulness or otherwise of reviving calls for a treaty is an important discussion to have amongst supporters for Aboriginal rights. As Pilger himself acknowledges, Indigenous people in places such as Canada and the US may have treaties, but still suffer grinding oppression.

What is urgently needed is to rebuild the kind of social movement for Aboriginal rights of the 1960s and 70s that won the beginnings of self-determination and land rights as an alternative to the assimilation agenda. As the Intervention politics lurches on we can be sure that alongside the horrors there will be resistance. This can be the basis for building mass campaigns that could reverse the suffering displayed vividly in the film – stop the intervention, and fight for resources that might allow real community control.

For screening times see utopiajohnpilger.co.uk