Jean Parker looks at why the massive February 2003 global weekend of action didn’t stop the Iraq war—and the claim that this proves protests don’t work

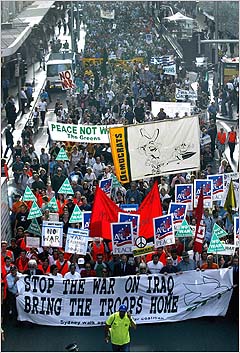

On the weekend of February 14-16, 2003 more than 30 million people marched against war on Iraq, in the largest co-ordinated demonstrations in human history.

Solidarity’s predecessor publication described how, “Central Melbourne came to a total halt on the Friday evening as a quarter of a million Victorians massed against the war. The turnout represented one in 10 adult Melburnians.

“As the first marchers filled Federation Square, the rear of the demonstration was still six blocks back. Many stood patiently in the heat for two hours only to go home without marching.

“Organisers say up to 100,000 protested in Adelaide, 100,000 in Brisbane, 20,000 in Perth, 15,000 in Canberra, Hobart and Newcastle. The biggest demonstration of all took place in Sydney. More than 350,000 filled Hyde Park and spilled into Elizabeth and surrounding streets.”

The ten year anniversary is a time to assess the real impact of that movement, and how successful US imperialism was in achieving its “Project for the New American Century”.

The ten year anniversary is a time to assess the real impact of that movement, and how successful US imperialism was in achieving its “Project for the New American Century”.

Today very many people see the massive anti-war marches as a failure. If millions could march and it still didn’t stop the war, clearly protests don’t work, they say. There are two problems with this. Firstly the “other global superpower”, as the anti-war movement was called in The New York Times, constrained the US in its plans for further wars in the Middle East.

There can be no doubt that without a movement to discredit Bush’s doctrine of pre-emptive war the US military would have launched further invasions and occupations in the Middle East. The “Project for the New American Century” that guided the US occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq was based around the idea that a US military offensive in the Middle East could be used to bolster the US’s geo-political dominance relative to economic rivals in Europe and China. The point was to stamp US control over the world’s primary oil-producing region.

Bush never wanted to stop in Iraq. The invasion was supposed to be a “cake-walk” that would be completed in weeks. On top of the countries Bush initially included in the “Axis of Evil” in 2002 (Iraq, Iran, and North Korea) the list of “rogue states” grew to include Syria, Libya, and even Cuba.

Fast-forward ten years and the US is in retreat in the Middle East. The combination of the armed Iraqi resistance and broader political opposition forced the US to pull out of Iraq more quickly than it wanted, left it barely controlling a fraction of Afghanistan and, after having to negotiate with the Taliban in order to maintain a semblance of control.

Iraq is currently the world’s third largest oil producer. But this oil is not controlled by the US. By 2035, 70 per cent of Iraq’s oil will be consumed by China. This is exactly what the Project for the New American Century was designed to prevent.

George Bush, Tony Blair and John Howard managed to push ahead with the invasion and occupation of Iraq in spite of the level of global opposition on the streets. But there were real costs for them. The movement trashed the lies behind the war on terror in the belligerent countries. It gave confidence to the Iraqis resisting the occupation.

Secondly, while protest works—we have seen this confirmed in the successful uprisings against Tunisian Dictator Ben Ali and his Egyptian counter-part Hosni Mubarak—not all protests are equal. The movement against the invasion of Iraq needed to mobilise greater social and industrial power to get to the point of stopping the war. The walks against the war were essential but insufficient.

While the size of the street marches were a demonstration that public opinion was against the war, Prime Minister John Howard made it clear he was prepared to ignore this. Breaking Australian support for the US required escalating the cost for the government through strikes and industrial action. By costing them lost profits, this hurts big business and can bring the economy to a halt. If workers begin to use this kind of economic power, no government can afford to ignore them.

This is exactly what happened during the Vietnam War. The Vietnam Moratorium marches were held on weekdays—meaning they were mass strikes. To achieve industrial action that can actually disrupt capitalism during business hours requires convincing wide layers of trade unionists and working class activists. The movement needed to explain why the war was a class issue and why more disruptive and costly action was necessary.

While the protests before the invasion of Iraq were numerically larger than the Moratorium marches during the Vietnam war, the Vietnam movement was deeper and more radical.

Occupying Iraq

After the invasion of Iraq began, there were also a number of political challenges that confronted the movement. The lack of understanding about the kind of action that would be necessary to stop the war meant many were demoralised when, despite the demonstrations, the war went ahead.

Another crucial issue was the Islamophobia used to justify the war on terror. This helped John Howard and George Bush sell the argument that if the US withdrew after the fall of Saddam, the country would “descend into civil war”.

In fact it was US divide and rule pitting Sunni against Shia and Kurd, and arming factions amongst each, that created the problem of sectarian violence.

Proving this, the number of sectarian killings has dramatically dropped since the US troops have left. In 2006 the number of civilians killed was 35,000, but by 2010 it had fallen to 1578. But the scars of sectarian cleansing overseen by the occupation remain with the country virtually divided into three areas—Central and Southern Iraq controlled by the Shia Maliki government, the West a Sunni enclave, and the Northern region a semi-autonomous Kurdish area with strong links to the US.

Opposing the Islamophobia at home, and the scares about Islamic terrorism, was also necessary to undercut the justification for the war on terror. In Australia the anti-war movement collaborated with the Muslim community to fight against Howard’s draconian anti-terror laws. Of course there were dark times like the 2005 Cronulla race riots, when the constant racism from Howard’s war spilled onto the streets.

But anti-racist activism as part of the anti-war movement and the refugee movement meant that there would always be groups of people defending Muslims, preventing further “Cronullas”.

All the warnings of the anti-war movement proved correct.

Think about what would have happened if Iraq wasn’t invaded and Saddam was still ruling when the Arab Spring began. The anti-war movement always argued that Iraqis were capable of overthrowing Saddam themselves.

The revolutionary process continuing in the Middle East and North Africa confirms that real liberation comes from the masses, not US tanks. Saddam was no stronger than Mubarak, and Iraqis were no less prepared for resistance than Tunisians.

Instead the reality of Iraq today is of a population brutalised on the basis of lies. If the US hadn’t invaded at least another million Iraqi civilians would be alive. Because the occupiers refused to count this number is contested.

In 2006 the British medical journal The Lancet calculated at least 600,000 civilian deaths as a result of the invasion and occupation. Based on the increases reported by Iraq Body Count—which only records publicly reported deaths, the real toll by the time the US left in 2011 must be nearly 1.5 million people.

A further 2.25 million Iraqis fled to Syria and Jordan as refugees by 2007. Iraqis have been left with a devastated country. Outside Baghdad less than 8 per cent of homes are connected to sewage systems. Only 22 per cent of water treatment plants have been rehabilitated. The unemployment rate in 2012 has finally fallen from the post-war highs of 60 per cent to 16 per cent.

The anti-war movement also played a role in Howard’s eventual defeat in 2007. It was the anti-war movement that exposed the plight of David Hicks and Mamdouh Habib in Guantanamo Bay.

Howard’s complicity in the invasion of Iraq and in the concentration camp at Guantanamo Bay were turned from issues the Liberals could use to win votes into an electoral liability. Howard was forced to ask his friends in the US administration to get David Hicks home in early 2007. When Vice President Dick Cheney, and later Bush himself came to Sydney, Howard was embarrassed by bitter scenes of mass civil disobedience.

These sporadic displays of direct action were an important ideological counter-weight to the war on terror. In the decade since the fall of Baghdad massive opposition to the imperialist projects of the US, Britain and Australia has prevented the forward-march of the war on terror.

By achieving this the millions who participated in anti-war movements in countries like Australia held hold open the space for the Arab Spring—for the populations of the Middle East to speak for themselves and write their own history.