Opposition to the nuclear industry in Australia has managed to hold back its expansion—including through union action to ban uranium, explains Joshua Look

Announced in September, the AUKUS security treaty saw the Australian government move to purchase US-built nuclear-powered submarines.

Aimed against China, the deal has predictably escalated tensions in the Asia-Pacific.

This willing embrace of nuclear technology, especially for military use, is a dangerous escalation of Australia’s involvement in the nuclear cycle. The highly enriched uranium inside the nuclear submarines’ reactors could even be repurposed to create nuclear weapons.

Reminding ourselves of the proud history of Australia’s anti-nuclear movement offers valuable lessons into how to build a movement to counter this latest push towards embracing nuclear technology.

Australia’s sordid nuclear history began following World War Two, when the country was home to both uranium mining and British weapons testing.

From 1952 to 1957, the United Kingdom conducted 12 major nuclear tests in Australia at Emu Fields, Maralinga (near Woomera), and the Montebello Islands. “Minor” tests continued until 1963.

These tests did untold damage to the environment, to the workers exposed to radiation during the tests, and to the Indigenous populations of the area who were forcibly removed from their lands, as exposed in the McClelland Royal Commission released in 1985.

Most people opposed these tests, with polls in 1957 showing only 39 per cent of the Australian population in support and 49 per cent opposed.

But the 1950s and early 1960s saw only small and infrequent protests around the “Ban the Bomb” movement.

However in 1969, the Australian Government proposed a major nuclear reactor to be built at Jervis Bay, around 200km south of Sydney. Local opposition groups formed, and the local South Coast Trades and Labour Council refused to work on the project, playing a critical role in its eventual abandonment in 1971.

By then a new wave of public consciousness began in response to the Vietnam War.

In 1966 France conducted its first of 193 nuclear tests across French Polynesia. These tests were conducted with little concern for the local environment or populace, with research released last year suggesting the health impact to be much higher than previously admitted by the French Government, with up to 100,000 individuals affected by nuclear fallout.

The beginning of French nuclear testing in the South Pacific produced a more co-ordinated anti-nuclear movement.

In 1972 pressure forced the Australian and New Zealand Governments to launch a case against France in the International Court of Justice, on the grounds that nuclear fallout could reach the two countries. This resulted in the French ending nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll.

This period also saw the formation of multiple anti-nuclear NGOs and groups including CND, Peace Media, Friends of the Earth, the Australian Conservation Foundation and Greenpeace.

Mining

Australia’s role in uranium mining began to take centre stage, in the face of a major push to expand the industry. Australia contains 35 per cent of global uranium deposits, but until the 1970s mining had only taken place on a modest scale.

Even the Whitlam Labor government, elected in 1972 declaring its opposition to nuclear weapons and support for ratifying the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), supported a domestic nuclear power industry, the construction of enrichment facilities and an expansion of uranium exports.

Just prior to his government’s dismissal in November 1975, Whitlam commissioned a report into uranium mining with the aim of justifying its expansion. This report was handed down in 1977 and recommended extensive restrictions and conditions on any mining, warnings that were largely ignored by the Liberal Fraser government.

The mining industry worked hard to distinguish the idea of “clean” uranium for energy and “dirty” uranium for weapons, alongside the idea that exports of uranium could and would only be used for their intended purpose.

With Canberra determined to proceed with uranium exploitation, anti-nuclear activists formed the Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM) in Melbourne in early 1976 with a national summit held in Sydney in November the same year.

With the size and success of the recent anti-Vietnam War protests still fresh in mind, MAUM’s first national initiative was a signature drive “designed to involve supporters in bringing the debate directly to the Australian people”.

MAUM used their petition to put their case to the public by distributing copies of a “Uranium Declaration”, in order to explain the movement’s key demands to everyone who signed the petition, of which a five-year uranium mining moratorium petition was central.

MAUM collected 250,000 signatures over just a few months.

MAUM aimed to not only organise public demonstrations, finding major success with their first major protest attracting 10,000 people in Sydney in April 1977 and 20,000 across Sydney and Melbourne later that year, but also direct action through the disruption of uranium exports.

As one historian records: “In Sydney… there were night-time convoys of uranium across the city, travelling fast up one-way streets the wrong way, guided by NSW and Commonwealth police escorts, opposed in the dark by small assemblies at the docks”.

Union bans

Central to achieving this disruption was the close cooperation between groups like MAUM and rank-and-file unionists, who supported the movement through their facilitation of motions across multiple unions boycotting any work that supported uranium exports.

In May 1976 Jim Assenbruck, a railway worker in Townsville, was suspended from his job after refusing to load materials bound for the Mary Kathleen uranium mine in accordance with the policy of the Australian Railways Union. His suspension led to a national rail strike that ended in Assenbruck’s reinstatement. Brisbane wharfies coordinated for years with Friends of the Earth, warning them of incoming uranium shipments and how to best disrupt the ports from the inside.

From 20-23 June 1977, protesters invaded the docks in Sydney to disrupt the export of yellowcake (uranium oxide ore), supported by rank-and-file wharfies who stopped work in solidarity with the anti-nuclear cause. An ambivalent ACTU eventually forced a resumption of work, but not before it made major news headlines.

Two weeks later, Columbus Australia was forced to leave behind $1 million of cargo in Melbourne after over 150 protesters shut down the port for 24 hours alongside unionists acting against the wishes of their union leaders.

Such consolidated, widespread solidarity even forced the Labor Party, at its 1977 National Conference, to back a moratorium on new uranium mines, with the ACTU Congress introducing a similar motion two months later. This froze future mining, but allowed existing export orders to be fulfilled.

At a rank-and-file level, the movement established workplace anti-uranium groups to try to build stronger opposition to the industry. This resulted in a number of workplaces placing union bans on any work associated with uranium mining, including metal shops like Evans-Deakin and Sargeants-ANI in Brisbane.

In 1981 transport unions imposed new bans in an attempt to stop the export of any uranium even from the existing mine at Mary Kathleen and from the Lucas Heights reactor, holding up exports on the docks in Brisbane and Darwin for weeks on end.

But the ACTU leadership eventually succeeded in winding down these union bans following the actions. Labor dropped its moratorium on uranium the next year, nine months before winning government under Hawke.

Hawke’s Labor government introduced the “three-mine policy”, restricting uranium mines to just three nationally.

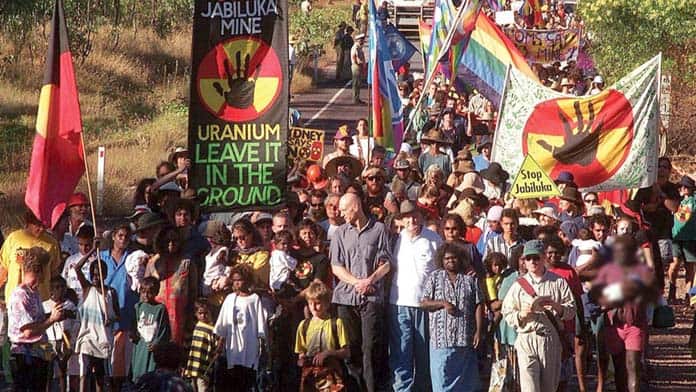

When this policy was abandoned under Howard in 1996, a campaign stopped the opening of a new mine at Jabiluka in Kakadu in 1998, after an eight-month blockade coordinated by Indigenous groups.

The nuclear industry remains controversial. Indigenous groups prevented the establishment of a nuclear dump site in Muckaty in central NT in 2014 and the question remains open to this day, with a site at Napandee to the north-west of Adelaide the current candidate.

Elements of the right including Clive Palmer, Craig Kelly, Tony Abbott and Barnaby Joyce have continually attempted to undermine opposition citing supposed economic benefits, national security and, more recently, the idea that nuclear power could help address climate change.

The price of uranium has been suppressed since the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, however if it ever recovers, mining companies could make another push to open new mines. There is little doubt that the efforts of conservatives to improve uranium’s reputation are aimed at laying the groundwork for future mining should it become profitable.

One strength of the anti-nuclear movement in the 1970s was its ability to communicate the threat presented by uranium mining in order to build public opposition.

Grassroots campaigning and local demonstrations in the suburbs built towards major city-wide demonstrations and protests.

In early 1977, only 34 per cent of Australians opposed the mining and export of uranium. By 1982 public opinion had been swayed, with around half the population against them.

Coordination and solidarity with unions provided the anti-nuclear movement not only invaluable political leverage, but the credible threat of widespread disobedience and the effectual disruption of destructive construction and mining operations. It is the best example of how social movements can partner with workers’ power to accomplish meaningful change.

It provides a blueprint for the wider climate movement going forward and an opportunity to strengthen the consciousness and political power of the working class.

With the Morrison government having just recently committed an additional $3.5 billion towards the purchase of US-made tanks, amidst skyrocketing COVID-19 cases, despite a crisis in hospitals and aged care alongside shortages of rapid antigen testing facilities and resources, the priorities of the ruling class are clear.

The time to build and mobilise a coordinated movement against this latest push towards nuclear weaponry and militarism is now.