Published September 2019

Contents

Big problems require big solutions

Capitalism vs the climate: Why we need system change

Workers and climate jobs

Indigenous rights and climate justice

Why global climate negotiations have failed

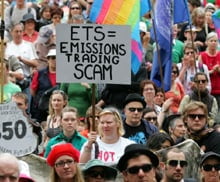

What’s wrong with carbon taxes and market solutions

Can lifestyle change help?

Solutions

The 1970s anti-uranium campaign—lessons from the past

1. Introduction

Our world is facing a climate emergency. Extreme heat and wild weather are already bringing home the reality of climate change to millions of people. July 2019 was the world’s hottest month on record, with scorching record temperatures across Europe, including Paris’s hottest ever day of 42.6 degrees. Africa recorded what is likely its hottest ever temperature of 51.3 degrees at Ouargla in Algeria.

Greenland temperatures were a shocking 10 degrees higher than average, causing its ice sheet to lose 12.5 billion tons of ice in a single day, the most ever recorded. Across the Arctic we have seen forest fires at “unprecedented levels”, according to scientific experts like Mark Parrington of the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service.

Australia, too, has seen record breaking heat in 2019. Rivers in NSW have dried up due to drought and the effects of water theft by corporate irrigators, killing millions of fish and leaving towns like Walgett without drinking water. Tasmania has been consumed by bushfires of a kind rarely seen before the last decade. Climate change is threatening the existence of wilderness areas there that will never recover if they burn. All this is happening much faster than scientists predicted.

But we are also witnessing a new wave of climate activism. In March 150,000 joined the second high school student Strike for Climate across Australia. Students have staged school walkouts worldwide, inspired by Swedish student Greta Thunberg’s protest outside the country’s parliament every Friday, with her sign declaring a “School strike for climate”. In April, tens of thousands joined Extinction Rebellion protests that occupied streets in central London for six days, demanding governments “tell the truth” about climate change.

But the re-election of Prime Minister Scott Morrison and his Coalition of climate deniers in May was a shock to the climate movement in Australia. His government refuses to adopt any credible policy for reducing carbon emissions, wants to extend the life of coal power stations and to lock in an expansion of fossil fuel extraction.

The election was a wake-up call for the climate movement. Particularly in mining areas in Queensland and NSW’s Hunter Valley, the Coalition and the far right won votes using the issue of coal jobs and the Adani mine. This shows the need to campaign much more seriously for new, public sector climate jobs, and to reach out to workers and trade unions.

There remains wide support for action on climate change. The issue ranked as the biggest threat to the country, nominated by 64 per cent of people, in this year’s Lowy Institute poll. Since the election climate activists have hit back, with Extinction Rebellion groups springing up across the country and school students organising another Strike for Climate on 20 September. But the mining corporations, power companies and big business in general have huge profits at stake—and will fight to defend them. Fossil fuels are literally at the heart of the modern capitalist economy. This pamphlet is designed as a contribution to the fight for our future. It aims to discuss the challenges the movement faces—and why stopping climate catastrophe means changing the system.

2. Big problems require big solutions

Our planet sits on the brink of catastrophic warming that could render large areas of the globe uninhabitable for many species—including ourselves. In recent years climate scientists have observed what is happening to the planet with increasing panic. In December 2018 a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said there were just 12 years left to keep climate change to a level that avoids devastating consequences. It warned that warming needs to be kept to 1.5 degrees—when we have already seen just over 1 degree temperature increase already.

The “carbon budget”, or amount of carbon that can be burnt while remaining within this limit, is just a decade’s worth of current emissions levels, it said. This means the world needs to cut emissions by 45 per cent by 2030 and get to net zero emissions by 2050—implying that rich countries like Australia need to move far faster, since there are developing countries whose emissions will increase as they extend electricity to some areas for the first time. BBC environment reporter Matt McGrath has declared that world leaders have 18 months to put in place a more serious plan to slash emissions before such a timetable becomes impossible.

Current levels of carbon dioxide, which have increased from pre-industrial levels of 280 to 415ppm today, are already dangerous. The last time carbon dioxide levels were similar to today’s, three to five million years ago, sea levels were up to 40 metres higher and the temperature 3.5 degrees warmer.

Even at 1.5 degrees of warming, there will be serious ecosystem and species loss. Between 70 to 90 per cent of the world’s coral reefs will disappear, compared to their almost complete collapse if we reach 2 degrees. An increase in extreme weather events, like the forest fires we are already seeing in the Amazon, deaths from unbearably hot weather, and an increase in cyclones and flooding, are inevitable.

Current pledges to reduce emissions are nowhere near enough. “We’re not on track”, Professor Mark Howden, Director of the Climate Change Institute at the Australian National University, explained, “We’re currently heading for about 3 degrees or 4 degrees Celsius of warming by 2100.”

Tropical areas, including a third of Latin America and Africa and most of south-east Asia, would be uninhabitable for most of the year. According to Richard Betts of Britain’s Met Office Hadley Centre, “To the south and north of this humid zone, bands of expansive desert will also rule out agriculture and human habitation. Some models predict that desert conditions will stretch from the Sahara right up through south and central Europe.”

All this is primarily a consequence of burning massive quantities of fossil fuels since the industrial revolution. The carbon dioxide released acts like a blanket around the earth, trapping warmth from the sun. This process has led to significant warming events in Earth’s past. During the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum around 55 million years ago, global temperatures rose between 5 and 8 degrees as a result of the slow release of large amounts of carbon dioxide. Today’s level of atmospheric carbon dioxide is likely higher than at any time in the last three million years.

The problem we face is not simply a slowly warming planet. What scientists worry about is not steady, but abrupt climate change. From the study of ice cores drilled from below the surface in Greenland and Antarctica, scientists know that periods of warming in the last 800,000 years did not simply take place gradually. Instead there were dramatic shifts in temperature in very short periods. The warming events beginning 14,700 years ago that brought an end to the last ice age took just a few decades.1

This is because the Earth system can shift rapidly from one state of equilibrium to another. Small changes can accumulate gradually over many years, but once they pass certain “tipping points”, rapid changes take place. As geoscientist Richard B. Alley has put it, “abrupt climate change can occur when gradual causes push the earth system across a threshold.”2

One reason is the existence of “feedback mechanisms”. The build-up of polar ice caps, for instance, help to further cool the planet, as their white surface reflects heat, in a process known as the “albedo effect”. The release of large amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, from thawing of the Artic permafrost could also rapidly speed up global warming. The planet is already warming faster than scientists thought likely even a few years ago. Sea ice in the Artic has declined by 40 per cent in area and up to 70 per cent in volume at its summer minimum since satellite recordings began in 1979. Sea ice in the Antarctic is also beginning to melt, research by NASA scientists has revealed. If this continues it will speed up the melting of the vast ice sheets over the Antarctic landmass. The glaciers in the West Antarctic are especially vulnerable as they sit below sea level, meaning they are exposed to warming ocean waters.

The urgency and sheer scale of the problem we face determines the scale and nature of the action we need. It means we need radical measures such as replacing coal-fired power with 100 per cent renewable energy within ten years. There is no other way to solve the problem of global warming. And failure to solve the problem will likely mean human suffering on a scale not seen before in history.

3. Capitalism vs the climate: Why we need system change

Far from showing any decline, global emissions are still increasing, with levels in 2018 at an all-time high. Oil company ExxonMobil, “plans to pump 25 per cent more oil and gas in 2025 than in 2017”, The Economist reported in early 2019. “All the [oil] majors, not just ExxonMobil, are expected to expand their output.”

Most governments acknowledge climate change is happening. But they have been incapable of taking the kind of action required. This is because fossil fuel use is deeply embedded in the world’s industrialised economies. It’s not just the mining and power companies that are the problem. Every sector from manufacturing to heating, transport and agriculture is massively reliant on coal, oil and gas. As the IPCC’s report in late 2018 put it, “far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society” are needed.

This means that individual action to reduce consumption, through driving cars less or using green energy, cannot solve the problem. Residential use of electricity in Australia makes up only 21 per cent of total use. Industry uses almost 75 per cent. Transport is another major source of emissions. Enormous amounts of this are not in personal car use but in the transport of goods to supermarkets, export terminals or for use in manufacturing.

Military emissions are also enormous. The US military alone uses so much fuel across its vast fleet of ships, trucks and airforce that it releases more carbon pollution on its own than 140 countries. This means we need to make major structural changes to how production is organised and energy is produced across the economy. The problem is not that we lack the technology to transition to renewable sources of energy. It is that taking action means a challenge to the way capitalism operates. Under capitalism investment takes place based on what is most profitable in the short term. The needs of ordinary people and the planet are irrelevant, unless they can be commodified and sold for a profit.

Marx and ecology

The destructive operations of capitalism are unique in human history. Over time human societies have developed many different ways of relating to the environment. Aboriginal societies in Australia lived sustainably with the land without class divisions for at least 60,000 years, both adapting to and changing the environment.

Their use of fire, for example, significantly transformed the fauna and flora. It was not until capitalism was brutally introduced into Australia with the British invasion that sustainability became an issue. Although environmental damage, such as the deforestation and soil erosion on Easter Island 1300 years ago, occurred in previous class societies, the magnitude of capitalist environmental degradation dramatically surpasses anything previously. Climate change is only the most obvious of a series of ecological crises we are facing. Scientists believe Earth’s sixth mass extinction is underway, with a quarter of all species facing extinction due to land clearing and habitat loss, pesticides, and the changing climate. There has been a 60 per cent decline in wild animal populations since 1970, according to the latest WWF Living Planet report.

Industrial agriculture run on the basis of short term profit has meant unsustainable practices that are producing soil erosion and desertification. A UN-backed study in 2017 said 24 billion tonnes of soil was being lost each year, with a third of the world’s land already severely degraded. Agriculture is also depleting underground aquifers and polluting rivers with huge amounts of manure, chemicals and pesticides. And more than 8 million tonnes of plastic ends up in the oceans each year, a material that has only been mass produced since the 1950s. Capitalism has relegated nature to a mere “input” to a system driven by competition and profit.

As witnesses to the early stages of capitalism’s development from feudalism in the 1800s, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote about the destruction of nature as being inextricably connected to the development of industrial capitalism. This anticipated much of present-day ecological thought.

The ecological aspects of Marx’s thought, like so many others, have been distorted by the historical association of Marxism with Stalinism in Russia. Stalin’s rule saw massive environmental destruction as he drove a massive effort to industrialise in order to compete with the West. Stalinist Russia was not socialist or communist—it is better understood as being “state capitalist”—founded on the defeat of the revolution of 1917 and driven by the same logic of capitalist accumulation as in the West.

At the centre of Marx’s critique was the idea that capitalism had created an “irreparable rift” in the “metabolic” interaction between human beings and the earth. This reflects one of Marx’s key ideas—that human beings, like other animals, are a part of nature and rely on nature for the maintenance and reproduction of life. Yet we are also distinct from other creatures in that we do so through a process of conscious labour, with a capacity for planning and thinking through the way we relate to the natural world in a way no other creatures can.

The rift that Marx described was a result of the way capitalism uprooted previous modes of existence and their specific relations with nature. This included the creation of new agricultural technologies and the growing division between town and country. Since then we have seen the development of entire economies based around the industrial use of fossil fuels.

Fossil fuels

Reordering our society to strip out the use of fossil fuels will impose significant costs and a hit to corporate profits. It means retiring still profitable coal and gas power plants and meeting the costs of replacing them with renewable energy. It means replacing fleets of trucks with a rail freight system run off renewables. It means increasing the cost of construction through better energy efficiency standards for buildings. And it means transforming manufacturing processes through using electricity instead of the direct use of fossil fuels.

Taking action also threatens the profits and investments of the world’s wealthiest and most powerful corporations. Just 100 companies were responsible for 71 per cent of global emissions between 1998 and 2015, according to the Carbon Majors Database report. Reining in carbon emissions means oil, coal and gas companies will need to be shut down—threatening literally trillions of dollars in investments. Fortune magazine’s list of the world’s ten biggest companies for 2018 includes five oil companies, two car manufacturers and a power company. The minimum to make the list was revenue of $340 billion.

The same is true in Australia, with mining giants BHP and Rio Tinto both among the ten largest companies. Australian exports of coal, oil and gas were worth $230 billion last year. A rapid expansion of offshore gas drilling is expected to see Australia become the world’s largest gas exporter this year or next. And Australia remains overwhelmingly reliant on fossil fuels for power generation, with coal providing 60 per cent of power and gas another 20 per cent. The four big banks are also deeply implicated, with campaign group Market Forces estimating they have lent $88 billion to fossil fuel projects in the last ten years.

The other problem is that capitalism is based on competition between rival companies. A transport company that decided to reduce its emissions by using more expensive electric vehicles, as opposed to trucks run by petrol or diesel, would have to put up its prices and would quickly go out of business.

Class power

The scale of the wealth and profits of the fossil fuel companies give them enormous power. Not only can they pay for hundreds of lobbyists and multi-million dollar advertising campaigns, they provide billions in tax revenue and have the ability to sack hundreds of thousands of people. In the context of a capitalist society, this gives them enormous influence over governments—no matter which party is in power.

Just look at how the mining industry in Australia responded to the prospect of losing a small slice of their profits through then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s plan for a mining super profits tax. The mining bosses poured $22 million into a massive ad campaign against the tax, claiming jobs would be lost and the Australian economy destroyed. The government scurried into an embarrassing political back-down, removing Kevin Rudd as Prime Minister and slashing the tax rate.

The power of capitalists outside parliament means that simply electing better politicians will not bring change. Standing up to the power of these companies requires a mass movement of ordinary people. We need to demand government action to make massive investments in public transport and renewable energy and impose more energy efficient design of buildings, appliances and cities. All of this means challenging the usual operation of the “free market” and moving away from the idea that it can solve society’s problems, promoted by neo-liberal orthodoxy for the last 40 years.

Forcing this kind of action will require mass protests and more walkouts from schools and universities. Marching on the streets, and actions like blocking traffic, can cause disruption and keep demands for action on the political agenda. They are vital for drawing people into social movements and building their confidence to fight. But a movement that remains simply at the level of mass marches is not enough.

In 2003 hundreds of thousands marched across Australia against the Iraq war. Public opinion and the democratic will of the population was overwhelmingly against the war. But the government sent troops into Iraq anyway. The movement simply did not have sufficient power to force the government to back down.

The main power ordinary people have comes from the fact that the working class keeps the economy running. It is workers who drive the trains, run the power stations and the ports, operate the factories, keep supermarkets stocked, and hospital services running. Workers’ strike action has the capacity to shut down production and cost businesses millions of dollars in lost profits. This is the kind of power that can force those who run society to take action. It is why trade union support for climate action is vitally important, as a step towards mobilising workers’ power.

The greatest mass movements of the past have been based on the power of the working class. The anti-Vietnam war movement reached its height in the 1970s Moratorium marches, as workers “stopped work to stop the war”. The fight for equal pay for women involved women and men striking to win that demand. Apartheid in South Africa was rocked by mass demonstrations and finally brought down by mass strikes.

Workers in Australia have used their industrial power to fight for the environment before. Kelly’s Bush in Sydney remains parkland today because the Builders Labourers Federation refused to do the destructive work the developers wanted. Workers in the 1970s refused to move uranium exports.

Winning the mass of the working class to act on climate change means the movement must put the issues of inequality and jobs at its centre. Ordinary people should not have to pay to deal with climate change through job losses or cuts to living standards. The corporations who have created the crisis through polluting the planet should pay, through taxes on their profits and on the wealthy elite who control them.

Constructing such a movement is an enormous challenge. It means supporting struggles against capitalism on every front—from the racist scapegoating of refugees to unions on strike for higher wages. But it is the only kind of action that can avert disaster.

4. Workers and climate jobs

The federal election result came as a shock to the climate movement. This was supposed to the “climate election”, a demonstration of the support for action on climate change. And the Adani coal mine was a major issue during the campaign. Yet in Queensland, which was crucial to the Liberals’ re-election, a campaign in support of Adani and coal mining jobs delivered Scott Morrison regional seats including Capricornia, Dawson, Flynn and Herbert. One Nation also picked up votes through a campaign of open climate denial, both in Queensland and in NSW’s Hunter Valley coal region where it polled 21.9 per cent in one seat.

Labor’s two-bob each way—with Bill Shorten refusing to oppose Adani but also saying he might review it—made it look like he wouldn’t defend coal miners’ jobs. Labor offered no serious alternative plan for jobs in these regions. This showed dramatically that climate action at the cost of workers’ jobs and living standards will not win popular support, and can end up boosting the far right.

The climate movement’s focus on the Stop Adani campaign without any serious campaign for climate jobs was a disaster. It led Queensland CFMEU mining division leaders to threaten to campaign against Labor candidates who were not pro-Adani, and saw many of their members vote for the right. Bob Brown’s Stop Adani convoy—which charged into hostile coal mining areas in north Queensland during the middle of the election campaign—backfired badly.

Taking the issue of workers’ jobs seriously is a life or death issue for the climate movement. This is not simply a question of winning over majority support. The movement also needs the support of trade unions and organised workers in order to build the power to force change. The issue of jobs is an obstacle to winning the active support of the union movement as a whole, not simply unions in coal-dependent areas. One of the arguments run by Australian Education Union officials in Victoria against actively calling on teachers to join the March climate strike was that the CFMMEU did not support the demand to stop Adani.

In regions like the Latrobe Valley and the Hunter, which are dependent on coal jobs, communities are understandably worried. From the car industry in Detroit, to the steel industry in Newcastle, the shutdown of a large single industry has often devastated communities. Unions have been on the back foot for the past three decades—privatisation in the Latrobe Valley resulted in tens of thousands of job losses. Workers are cynical that they would be looked after in a transition away from coal. To win those workers, we will need to provide practical examples where the climate movement fights alongside workers. Simply talking about how climate action can provide jobs is not enough.

A just transition

Renewable energy technology could create many more jobs than currently exist in the power industry. One study by academics at Newcastle University looked at the impact a transition to renewable energy would have on jobs in NSW’s Hunter Valley. The Hunter region is a heavily coal-dependent community—housing four coal-fired power stations and coal mines that employ 9000 people. Shutting down all the power stations tomorrow would result in about 1300 direct job losses. But the report estimates that turning the region into a “renewable energy ‘Silicon valley’” would create between 7500 and 14,300 jobs.

Installing solar panels and wind turbines would create jobs in manufacturing, as well as installation and maintenance. According to the report, “If manufacturing is established in the Hunter to service the NSW renewable industries, the lower estimate [of jobs created] is 9400.”

There would need to be a transition to make sure workers in the coal industry received re-training in new jobs through government assistance programs. We also need to make sure climate jobs are well-paid, and unionised, like those they replace in the mining and power industries. It is not just the coal industry that will be affected in a serious climate transition. Many other jobs will have to be transitioned. For instance airline workers will be affected by a transition to high-speed rail, and truck drivers by taking freight off roads.

The best way to deal with this is to ensure there are job guarantees. For instance, there are current procedures in the public service in the case of departmental restructuring that allow workers to move to new jobs, keeping their rate of pay and years of service. Workers currently in fossil fuel industries deserve the same kind of guarantees. Everyone should have a right to work and a right to a decent income. Re-nationalisation of the power industry and airlines is part of ensuring public control of power generation and would make such guarantees more likely. A transition like this would ensure that business, not working class people, bear the costs of the transition away from dirty energy.

There are a wide range of jobs that could be created, from retrofitting and constructing energy efficient buildings and housing to recycling and land management. The ACTU released a report in 2008 which claimed that, “strong action on climate and industry policy could trigger the creation of an additional 500,000 jobs… by 2030”. Another CSIRO study estimated that the action needed to cut carbon emissions could generate between 230,000 and 340,000 additional jobs.

Former coal workers in South Australia fought for the Port Augusta Solar Tower project in the wake of the closure of the coal-fired power station there. The project had won a tender to supply electricity to the state, but recently collapsed due to lack of finance. This was a perfect opportunity for the climate movement to step in and fight for government to build the project, which could have been a win for renewables and jobs.

Following the election result, there have been some important steps in the right direction. The National Union of Workers released a statement after the election calling for a just transition, climate jobs and a Green New Deal. The School Strike for Climate grouping, which is organising the September Climate Strike, has encouraged unions and workers to join them this time. They have shifted decisively since the federal election to emphasise the need for a “just transition” for workers and communities currently dependent on fossil fuels, and offered statements of solidarity for striking workers at DP World and for the union movement as a whole against the Ensuring Integrity Bill. The National Tertiary Education Union has passed motions in NSW and Victoria committing to “the widest possible stoppage of work and study” to attend. We need to build a climate movement which puts the issue of jobs and workers’ living standards at its centre.

5. Indigenous rights and climate justice

The destruction of ecosystems in Australia began with British colonisation in 1788. For more than 60,000 years, Indigenous people managed lands and waters across this continent with systems of philosophy and law fundamentally grounded in intimate, sustainable relationships with the natural world.

The expansion of pastoral capitalism through the 19th century in Australia required a genocidal war against Indigenous peoples fighting to defend their lands. Mining and agricultural interests have driven further dispossession and destruction.

Despite this, many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have retained profound connections to their ancestral lands. They have never given up struggles to regain control, or aspirations to restore land management practices grounded in respect and reciprocity. These struggles have had a profound impact on the development of ecological movements in Australia and the return of stolen lands is crucial for climate justice.

Indigenous people leading blockades and protests to defend their lands have been at the centre of many iconic environmental campaigns. At Noonkanbah in WA in 1980, Yungngora people blockaded to stop drilling for oil on sacred land and gained solidarity from the ACTU, with unions banning development. At Jabiluka in Kakadu in the late 1990s, resistance from Mirrar people inspired an international campaign that stopped a new uranium mine.

Across the country, Aboriginal people are still on the front lines defending their country. At Borroloola in the NT, Aboriginal people have led numerous protests and are preparing to blockade fracking operations. The mass fracking planned in the NT would unlock a carbon bomb of shale gas deposits. Gambayngirr people are leading a community blockade at the headwaters of the Kalang River near Bellingen to stop logging operations.

Despite recognised Native Title claims over much of the continent, Native Title gives Aboriginal people no rights to veto mining or other destructive developments. Wangan and Jagalingou people have had their Native Title rights extinguished to allow the Adani coal mine to proceed, but continue to blockade. Many IPCC reports call for strengthened Indigenous rights across the world to help protect biodiversity and stop fossil fuel expansion.

There are now large areas of Australia that have been converted voluntarily by Native Title holders into “Indigenous Protected Areas”. These make up almost half of Australia’s “conservation estate” and are often used by the Commonwealth Government to tick boxes for international conservation targets. But Indigenous ranger groups trying to manage these areas, or restore other damaged landscapes, receive only 6 per cent of the federal conservation budget. In northern Australia for example, 650 Indigenous rangers are responsible for managing 154,000 square kms, whereas the same area of government-controlled conservation estate has been granted 20 times the funding.

A just transition through public funding of climate jobs should include large-scale funding for Indigenous people to lead broader efforts to rehabilitate and manage lands and waters. Indigenous burning regimes can help abate the massive release of carbon that comes from out of control bushfires. Reforestation of areas destroyed by agriculture and mining can play a major role in drawing carbon down out of the atmosphere.

There is also an urgent need to create employment to improve services and infrastructure in Indigenous communities already suffering from climate change. Torres Strait Islanders are currently suing the Australian government for climate inaction, as rising seas and storm surges threaten their communities and sacred sites. Last summer, in Western NSW, many Aboriginal communities sweltering in extreme heat also had no access to clean drinking water, as river systems collapsed under pressure from corporate irrigation and drought. In the tropical north, Indigenous communities cut off or facing evacuation as cyclones and flooding intensify often receive haphazard or discriminatory treatment by emergency services.

The climate crisis in the Pacific

Some of the world’s poorest people will face the worst effects of climate change—despite being least responsible for causing the problem. Pacific islanders are facing the complete loss of their homes. Cyclones and king tides in recent years have already caused unprecedented suffering, Pelenise Alofa, from the Kiribati Climate Action Network, told 3CR radio in Melbourne, while, “in other places like the Solomon Islands, PNG, Tuvalu and Fiji, people are already moving” as sea levels rise.

But as Pacific Island leaders pleaded for strong action on climate change at the Pacific Island Forum (PIF) in August 2019, Scott Morrison and Australian negotiators moved to ensure all references to stopping the expansion of the coal industry were removed from the forum’s communique.

Back in Australia, at a business forum in Wagga Wagga, Deputy Prime Minister Michael McCormack complained about, “people in those sorts of countries pointing the finger at Australia and saying we should be shutting down all our resources sector so that, you know, they will continue to survive”.

“They will continue to survive,” he said, because of “large aid assistance from Australia” and “because many of their workers come here and pick our fruit”. These disgraceful comments were slammed as “neo-colonial” by Enele Sopoaga, Prime Minister of Tuvalu.

Australia’s response to the climate crisis is grounded in more than 150 years of Australian imperialism in the region. Australia is manouvering both to ensure exclusive military domination, while also taking new opportunities for exploitation of the labour of Pacific Islanders on Australian corporate farms.

Imperialism and climate change

The Australian Defence White Paper in 2016 argued that climate change will drive “instability” and “state fragility” as Pacific peoples suffer from large-scale displacement and food shortages. But rather than act to cut carbon emissions, Australia is moving to lead “security” responses to potential social dislocation, to ensure corporate interests are protected first and foremost, and to check the rising influence of China in the region.

In 2017, Defence was at the centre of the launch of a new “whole of government” approach called “Pacific Step Up”, with policy documents pledging to “engage with the Pacific with greater intensity and ambition”. Australia is the largest provider of foreign aid to the region, and this funding is increasingly being concentrated in grants to police and the military, including the gifting of 19 new patrol boats to Pacific states.

The Federal Police and ADF are integrating their command structures with Pacific states and a new “Australia Pacific Security College” established with the Australian National University (ANU) will be part of a broader push to lead Australian training efforts. Fijian Prime Minister Frank Bainimarama has said that Australia’s “colonial attitude” would push his country closer to China. But despite these threats, Australia has successfully secured its position as sole funder of Fiji’s new Black Rock military base, which will train military personnel from across the Pacific, against a Chinese bid. Australia is also building a new base on PNG’s Manus Island.

Climate justice for the Pacific requires a rapid decarbonisation of the Australian economy and a demilitarisation of the Australian response to the unfolding climate crisis. Aid is urgently needed for Pacific-led climate mitigation and disaster response teams. And the people of the Pacific need unlimited rights to work in Australia and to change employers or return home whenever they need.

6. Why global climate negotiations have failed

Many hopes have been invested in world leaders forging a plan for global action on climate change. But the series of global summits, including the much hyped Paris conference in 2015, have been a failure.

Many in the mainstream media hailed the Paris agreement as “historic”. But the result was a sham. The final deal is voluntary, non-binding, and contains no penalties for countries that fail to reach their targets. Countries were even allowed to set their own emissions reduction targets as part of the deal.

In all, 176 countries made a pledge to reduce their emissions. These would still see global temperatures rise by 2.7-4 degrees—despite the agreement saying the aspiration was to keep warming to 1.5 degrees. And most countries are not on track to deliver even the emissions cuts they pledged. The world’s biggest economy is now run by Donald Trump, a climate denier who has torn up US support for the Paris agreement altogether. A UN Emissions Gap report released in November 2018 found that neither Australia, Canada, the EU, South Korea or the US look like meeting their 2030 targets. Emissions reduction efforts need to be increased five-fold to hold warming to the safe limit of 1.5 degrees, it said.

The problem of climate change has been known about—and discussed at the highest international levels—for decades. The first global agreement promising action to reduce carbon emissions was made almost 30 years ago, at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio. Yet emissions have just kept increasing. In 2018 they hit another record high of 33.1 billion tonnes, according to the International Energy Agency.

The global summits are shaped by competition between rival states such as the US, China and the EU determined to protect their own economies. They show the power of the fossil fuel corporations to sway governments and block action. No government wants its economy to bear a greater cost of cutting emissions than its rivals. So each country works to make sure their businesses get a better deal than overseas competitors. This is why, as Marian Wilkinson wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald, the Copenhagen talks in 2015 were, “bogged down in an elaborate game of chicken with the players waiting to see who will blink first.”

The European Union, for instance, is less reliant on coal and per person emits less than half the carbon emissions of the US.3 That means the cost for the US economy in curbing its emissions will be higher than in Europe—which explains why the US has been far less willing to take action.

This is a result of the competition structured into capitalism. To maintain profits, corporations must maintain a competitive advantage over their rivals. A company capable of lowering its production costs and undercutting rivals can drive others out of business. So no national government is going to voluntarily shut down polluting industries or impose higher production costs. This is why Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s excuse for not acting on climate change is always that serious action would mean, “taking a sledgehammer to our economy”. The Labor Party share the same underlying approach. When Labor’s Kevin Rudd was Prime Minister he declared, “I have said consistently, Australia will do no more and no less than the rest of the world”.

World leaders are engaged in a game of imperialist competition, defending the interests of their country’s major industries. Unless there is pressure on them from a mass movement involving the organised working class, governments will always put business profits before the planet.

7. What’s wrong with carbon taxes and market solutions?

In 2012 Julia Gillard’s Labor government introduced a carbon tax, with the support of The Greens and many in the climate movement. It aimed to force companies and consumers to reduce pollution through putting a price on carbon emissions (a “price signal”) that meant they would have to pay more for polluting products or services.

But the whole exercise was a disaster. The carbon tax forced ordinary people to bear the cost of tackling climate change. Despite talk of making the polluters pay, it was designed so that companies would pass on the cost through increasing electricity prices. This was acknowledged from the outset. Government climate adviser Ross Garnaut’s final report admitted, “Every dollar of revenue from carbon pricing is collected from people, in the end mostly households, ordinary Australians. Most of the costs will eventually be passed on to ordinary Australians.” He continued, “In the long run, households will pay almost the entire carbon price as businesses pass carbon costs through to the users of their products”.4

This meant the carbon tax was a gift to Tony Abbott and the Liberals. It allowed Abbott to pose as the defender of workers’ living standards by promising to scrap it. Initially the impact on power prices and the cost of living was small, and the Labor government attempted to provide compensation to low income earners. But in the face of power prices that were already on the rise, and concerns about the cost of living, the carbon tax got the blame. It was never popular, with an Essential poll in October 2013 recording 47 per cent opposed it and only 39 per cent in support. To make matters worse the carbon tax was designed to increase over time as the efforts to reduce emissions scaled up. This would have locked in the principle that ordinary people had to pay the cost of climate action and done serious damage to living standards.

In a context of low wage growth, and decades of privatisation and cuts to services under the banner of neo-liberalism, working class people have become increasingly bitter about the growth in inequality. Climate policies that hurt workers’ living standards will never win broad popular support.

At the time there was a large climate movement. The first Walk Against Warming in November 2007 mobilised 50,000 people in Melbourne, and 100,000 nationally. A grassroots Climate Emergency Network in Melbourne grouped together 30 active local groups with general meetings of up to 200 people at its peak. A series of national grassroots Climate Action Summits drew between 300 and 500 activists.

Tragically, large sections of the movement, as well as the big environmental NGOs, GetUp and The Greens, supported the carbon tax. In 2011 they organised large rallies to “Say Yes” to the policy. But all the efforts to build support for the carbon tax went nowhere. Tony Abbott and the Coalition won the 2013 election in large part on a promise to scrap the carbon tax, and it was repealed in 2014. Enthusiasm for action on climate change in general dropped as a result of the carbon tax. In 2006 the annual Lowy Poll showed 68 per cent viewed climate change as a “serious and pressing problem” requiring action. This was down to just 40 per cent in 2013.

Delaying change

Carbon taxes delay the changes necessary to deliver emissions cuts on the scale needed. This is because they are designed to reduce emissions at the “lowest cost”, delivering small, gradual decreases. But the lowest cost way to reduce emissions is typically to make the existing polluting industries slightly less polluting, rather than replace them with the zero emissions technology needed.

So instead of a plan to ramp up renewable energy and start building wind turbines and solar power, the carbon tax aimed to replace heavily polluting coal power with slightly less polluting gas plants. Former Climate Change Minister Greg Combet repeatedly admitted this, telling Lateline in 2011 that, “For baseload electricity generation it will be gas-fired electricity that we see emerge”—not renewable energy. But gas still releases greenhouse gases and is no solution to the climate problem.

Spending hundreds of millions of dollars on gas power plants obstructs the changes we need. The life of a new power station is 30 to 50 years—meaning they either lock in future emissions or result in the waste of millions of dollars in construction costs. The same thing is true right across the economy.

Did the carbon tax reduce emissions?

It is often claimed that the carbon tax in Australia was a success in reducing emissions. And it is true that during the two-year period it was in force, emissions dropped. There was a small 0.7 per cent decline in total emissions over the period. But the carbon tax only ever applied to about 60 per cent Australia’s emissions, and in these sectors the decline was larger, amounting to 3.38 per cent in total.

The one sector where there was a significantly higher decrease was in electricity, where emissions were down 9.66 per cent over the two years. Without this decline, overall emissions would have increased during the period. But most of the drop in electricity emissions was not the result of the carbon tax.

Part of this was due to a decline in energy demand. Factors in this include the growth in rooftop solar panels, the Mandatory Renewable Energy Target (MRET), and closures in manufacturing like the Kurri Kurri aluminium smelter. The MRET is a separate policy that forces power companies to meet a target of 41,000GW of power from renewable sources by 2020 (about 20 per cent of electricity generation). It is this policy that has encouraged the growth in renewable energy, reducing the amount of power produced by fossil fuels. Most rooftop solar panels were also installed as a result of state government subsidy schemes—not the carbon tax.

A further factor was that hydroelectric generators stored water instead of using it to generate power in the year before the carbon tax, in order to make more money during the carbon tax period. But once this water was used, hydro-electric generators dropped back to more normal levels of power generation after the tax was reversed. An outage due to flooding at the Yallourn brown coal power station in Victoria also reduced its emissions in 2012.

Carbon Trading

Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS), which are also known as carbon trading schemes, are another type of carbon price. The carbon tax introduced by Labor and The Greens was designed to become an ETS after three years.

Emissions trading involves setting a desired cap on total carbon emissions, say a 5 per cent reduction on the previous year, and then either auctioning or giving away permits that allow companies to release that amount of carbon. Those able to make larger cuts to their emissions can sell their excess permits to other companies unable or unwilling to reduce theirs.

US business interests like Exxon Mobil and Peabody Coal pushed this model into the Kyoto Protocol (which the US later refused to sign). This established emissions trading as a key mechanism pursued by governments around the world in response to climate change. It was modeled on the scheme used to reduce emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2-the cause of acid rain) in the US which aimed to reduce SO2 emissions in the US by 35 per cent after 20 years. By contrast in Germany, direct government regulation reduced SO2 emissions by 90 per cent between 1982 and 1998.

Europe established the first large-scale carbon emissions trading scheme in 2005. In Europe the carbon market crashed first in 2006, because too many permits were released, and again in 2008. This allowed companies to buy cheap permits and keep polluting, rather than cut emissions. After the first five year phase of the scheme wrapped up in 2012, polluting power companies had made somewhere between $23 billion and $71 billion from selling permits they were given for free. Czech electricity giant CEZ made so much money trading free permits it was able to use the proceeds to buy a new coal-fired power station. Because of the power of polluting corporations, handouts of free permits, as well as fraud and cheating are endemic to the system, and enforcement almost non-existent.

Carbon pricing is a fraud. It allows business as usual, leaving emissions and profits untouched, while absolving governments and industry of their responsibilities for the climate catastrophe that faces the planet.

8. Can lifestyle change help?

Many people see changing their individual behaviour, through lifestyle or consumer choices, as a way to help stop climate change. Governments and corporations want to encourage this view. They want us to focus on our consumption rather than force them to get serious about what really matters—things like renewable energy and public transport. But a focus on lifestyle choices is a distraction. Individual consumer action cannot solve the climate and environmental crisis. The essential problem is not consumption, but production controlled by an elite more concerned with their profits than the future of the planet.

In the shops there is a ballooning niche market in “eco-friendly” products. “Green” beers, detergents, nappies, chocolates, and even McDonalds coffee are sold in “carbon neutral” shopping centres. But Australia’s overall emissions have continue to rise.

Consumer activism has to compete with the billion dollar advertising industry—making it difficult for most consumers to know what real social and environmental impacts different products have. The use of “greenwashing” by corporations to give their products an aura of environmental responsibility is widespread. Australia’s big banks like NAB and ANZ trumpet their “carbon neutrality” yet continue to fund fossil fuel projects. And in the face of cost of living pressures, most people are not prepared to pay more for green products. Strict environmental regulations are needed over the way products are produced, to force companies to reduce the emissions they require.

Another popular focus is on using less power in the home, through actions like the installation of energy-saving lightbulbs, or even rooftop solar panels. But household electricity consumption amounts to only 21 per cent of Australia’s total power use. And the amount of electricity that can be saved by changing light-bulbs is negligible—lighting uses only 6 per cent of residential power. Drastic reductions in household electricity use can only be achieved through government-enforced regulations on insulation in buildings and manufacturing standards to install a new wave of fridges and heaters that are energy efficient.

And the larger problem is that almost 60 per cent of Australia’s electricity comes from burning coal. Changing this will take large-scale investment in renewables.

Riding a bike instead of relying on petrol-powered cars has been another response to the alarming growth in carbon emissions. But Australia’s cities are designed around car usage. Many people cannot afford to live in the inner city or close to their work and are forced into the outer suburbs. Just 35 per cent of homes in Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney are within 400 metres of services running at least every half hour, according to the Centre of Urban Research. Public transport systems are inadequate and often overcrowded. To reverse the trends in car usage we need a significant increase in quality well-funded public transport.

The action needed to slash carbon emissions requires wide-scale government action. This will only happen through public pressure based on collective action. Those who run big business and governments have profited from the carbon polluting industries and are refusing to change. The urgent task is to collectively organise to build a social movement that can fight for the changes to production and investment that could really make a difference.

Is our diet destroying the planet?

The idea of changing our diets has become another increasingly popular response to the environmental crisis. Al Gore has gone vegan and actor Leonardo Di Caprio has thrown his name behind a film, Cowspiracy, which suggests that all we have to do to stop climate change is stop eating meat.

Emissions from animal agriculture do need to be addressed if we want to reach net zero emissions. But Cowspiracy paints animal agriculture as the number one climate villain by cherry picking wrong or misleading “facts” and “experts”. One of the film’s main claims is that, “livestock and their by-products actually account for… 51 per cent of annual worldwide greenhouse gas emissions”. This claim comes from the widely criticised 2006 UN Food and Agriculture Organisation report Livestock’s Long Shadow. It has been debunked by Simon Fairlie in his book Meat: A Benign Extravagance. He puts the figure at closer to 10 per cent. More recent data from the authoritative Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Report in 2014 comes to a similar figure. (It lists agriculture as producing 24 per cent of global emissions, of which methane produced by livestock accounts for 39 per cent).

Nor is it true that agriculture emissions are growing faster than those from other sources. The IPCC says, “emission from fossil fuels contributed 78 per cent to the total greenhouse gas emission increase between 1970 and 2010. Since 2000 emissions have been growing in all sectors except in agriculture”.

A focus on going vegetarian or vegan is ultimately demobilising—putting the emphasis simply on individual lifestyle change. Tackling climate change requires first and foremost a transition away from the use of fossil fuels like coal, gas and oil.

Simon Fairlie’s book points out that some meat production actually makes sense. He estimates waste food in Britain, which would otherwise be thrown away, could produce one-sixth of the country’s current meat consumption. As environmentalist George Monbiot has written, “If pigs are fed on residues and waste, and cattle on straw, stovers and grass from fallows and rangelands – food for which humans don’t compete – meat becomes a very efficient means of food production.”

Climate research group Beyond Zero Emissions’ has produced a Land Use Report which looks at how agriculture could be run more sustainably. It does recommend reducing herd numbers, and therefore eating less meat.

But it also suggests changes to production methods like rotational grazing (rather than burning used pastures), feed changes, selective breeding, and practices which increase soil carbon. Such changes would need “very significant investments” and require political change, it says.

A focus on what we eat ultimately ignores the need for massive change in agricultural production methods, blames ordinary people, and lets corporations, politicians, and capitalism off the hook.

9. Solutions

We need to transition to a zero carbon economy as fast as possible. Yet Prime Minister Scott Morrison continues to do the bidding of the climate deniers and coal fanatics in the Coalition. It was Morrison himself who proudly waved around a lump of coal in parliament to taunt supporters of climate action. Under the Coalition, Australia’s emissions have increased every year since 2015. The only way the government will meet even its own Paris Agreement target is through dodgy accounting tricks, through carrying over credits from the Kyoto agreement period.

Having abandoned former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s hopeless National Energy Guarantee, the only major policy the Liberals have left is the Tony Abbott-era Emissions Reduction Fund. This pays businesses to reduce their emissions and funds offset projects like re-vegetation. Although the scheme has spent $2.55 billion of a planned $4.55 billion, Australia’s emissions continue to rise.

In addition, the government has pledged to support a number of other energy projects, whether through a floor price, loans, small grants or other mechanisms, in an effort to increase electricity “reliability”. Their shortlist of 12 projects includes a coal power station at Vales Point in NSW. This is less a climate change policy than an effort to manage the looming closure of several power stations. In a further indication of the government’s support for coal power, Energy Minister Angus Taylor has cheered the news that Liddell power station’s operator would keep it running a year longer than planned, until April 2023. And he has also set up an inquiry to examine how to replace it, which will examine the option of government funding to keep it running even longer. Morrison has also agreed to spend $10 million examining whether the decommissioned coal plant at Collinsville in north Queensland can be reopened.

Renewable energy

Electricity generation is Australia’s largest single source of carbon emissions. The answer to this is 100 per cent renewable energy. And despite the Coalition’s efforts, the amount of renewable energy in Australia has been increasing rapidly. Around 21 per cent of Australia’s electricity came from renewables last year (including hydro power). In 2018, there was a surge in large-scale solar power installations, with 1442 MW of generation capacity installed, according to the Clean Energy Council,5 equivalent to the decommissioned Hazelwood power station in Victoria. Two million households, or one in five, now have rooftop solar panels.

A report last year from the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), responsible for administering the National Electricity Market, estimated that renewable energy will reach almost 50 per cent by 2030 without any support from government at all. This is because three ageing coal power plants must be replaced by 2030—and the cheapest replacement is now renewable energy.

But the urgency of the climate crisis means we need a plan to retire all the existing coal and gas power plants. A target of 100 per cent renewable energy by 2030 is both necessary and achievable, but will require planning and direct government investment. Leaving it to the free market will not get us there.

When building new power plants, solar and wind power projects are now cheaper than fossil fuels. But the existing coal power plants, whose construction costs are already paid for, remain competitive. This means there could still be coal plants running until 2050 without government intervention.

As Mark Diesendorf from UNSW wrote in a detailed plan for the Australia Institute in November 2018, it is well established that renewable energy can provide all of our power needs. Computer simulation modelling shows that wind and solar projects distributed across a wide geographical area can provide most of our power needs, because when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing in one area, power can be used from somewhere it is.

There is also “practical experience when 100 per cent renewable electricity is already being reached for short periods of time in Denmark, Germany and South Australia”, he notes. Renewable energy supplied 74 per cent of Denmark’s total power needs in 2017, around half of it from wind turbines.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Energy Minister Angus Taylor claim we need “reliable” power that is “dispatchable” on demand, as an excuse to support coal. Yet batteries and other storage systems allow renewables to provide power that is “dispatchable” at any time of day too.

The Snow Hydro 2.0 project would be one method of storing power from renewable energy, pumping water uphill for release to power hydro turbines. It is expected to cost at least $4 billion and will be 100 per cent owned by the federal government. Another example is the $96 million Tesla battery in South Australia, subsidised to the tune of $50 million by the state government. It is the largest battery of its kind in the world, with a capacity of 100 MW capable of powering 30,000 homes for eight hours. This does, however, come at an increased cost.

Reaching 100 per cent renewable energy would also require upgrades to the electricity transmission grid to connect new solar and wind projects. This would also include new transmission lines to allow power to be sent across the country to where it was needed.

What cost?

Eight years ago climate advocacy group Beyond Zero Emissions launched a plan for 100 per cent renewable energy in a decade, showing the concept was technically possible. This showed that 12 large solar thermal plants spread across Australia could provide 60 per cent of our electricity needs, with wind turbines capable of supplying another 40 per cent. Much has changed since. Renewable technology has created at least 15,000 jobs, and costs have fallen dramatically.

Numerous plans to get to 100 per cent renewable energy have now been produced. The government authority AEMO even prepared its own report into 100 per cent renewables in 2013, with one scenario investigating a relatively rapid transition by 2030.

There will be significant costs to replace Australia’s ageing coal power plants in any case, as after around 50 years they are too expensive to repair, so that 60 per cent of their total generating capacity is due to go offline in the next 20 years.

A study from the ANU in 2017 estimated, after accounting for grid upgrades and storage, that a fully renewable energy grid could provide power for $93 per megawatt hour. Another study from Windlab, a renewable energy company, said it could be as low as $70 per megawatt hour. This is not far above current wholesale energy prices which have fluctuated between $50 and $100 a megawatt hour in NSW, Victoria and Queensland over the last three years.

The costs of new energy infrastructure are currently met through our power bills. But it is vital to ensure a rapid transition to 100 per cent renewables does not result in higher power prices. This would push up the cost of living for workers and the poor. We saw with the carbon tax introduced in 2012 how the threat of higher power prices undermines support for climate action.

The obvious solution is for government to step in directly and build renewable energy itself. This is not a new concept. Most of the coal-fired power plants and the electricity grid in Australia were initially built by government, because of the scale of investment required. And if the federal government spends money to subsidise renewable energy, it should take direct control of the investments, rather than hand control to private companies who will siphon off government money as profit. Taking power back into public hands would also allow the government to cap power prices and stop the prices increases we have seen in recent years, driven by privatisation.

In the US, democratic socialist Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s call for a Green New Deal to roll out renewable energy, jobs and infrastructure, and taxing the rich to pay for it, has been enormously popular. When the economic crisis hit in 2009, we saw governments announce their own major spending programs that show what is possible. In the US $700 billion was found to bail out Wall Street within a few months, and total US stimulus spending hit US $3 trillion. Kevin Rudd spent over $57 billion—although much of it could have been more usefully spent on renewable energy infrastructure instead of hastily constructed school halls and the disastrous pink batts that were simply designed to shovel money into the economy.

The money to fund a bailout for the planet is there. Since the mid-1980s corporate tax rates have been slashed from 46 to 30 per cent. Restoring the rate would raise up to $50 billion a year—which is more than enough to fund the transition. This would ensure the responsibility for paying for the transition was put on those who have created the problem of climate change—the big polluting corporations.

The transition we need also goes beyond repowering our electricity system. Energy efficiency measures, like the provision of insulation, solar hot water, and energy efficient appliances for every home could also make a serious dent in emissions. But these measures cannot be left as “consumer choices”, available only for those wealthy enough to afford them. They will not work unless government forces industry to build energy-efficient schemes into housing and construction. One report estimates this could cut energy consumption by 15 per cent by 2030.6

Our cities have been designed around car usage. However, with government investment a massive expansion of the public transport system could reduce most car use. Any remaining cars could be electric-powered.

10. The 1970s anti-uranium campaign—lessons from the past

11. Conclusion

Capitalism is pushing our planet towards climate catastrophe. The system has proven itself incapable of acting to solve the problem. To avoid disaster, we will need to build a social movement that fights against the power of the fossil fuel corporations and against the logic of profit.

Karl Marx’s path-breaking analysis of the new system, discussed earlier, did not simply involve analysing the way it destroyed both the workers and the environment on which it depends. He also saw that the capitalist system itself created the potential power to challenge it. In a famous phrase in the Communist Manifesto, Marx called the working class the “grave-diggers of capitalism” with the power to overthrow the system.

Capitalist production concentrates large numbers of people in the modern day workplace—from traditional factory workers and construction workers to call centre workers and teachers. Through strike action, workers have the ability to stop environmental destruction where it begins—at the point of production. But the working class also has the potential to create a new form of society, socialism, through taking over the whole economy and putting it under democratic control. This would mean a society run according to the needs of ordinary people and the planet, not corporate profits.

Marx’s argument about the power of the working class to challenge capitalism has been confirmed again and again in the 150 years since. At high points of class struggle the working class has created new democratic institutions, based on delegates from workplaces, which have begun to take over the running of society in the interests of ordinary people. We have seen examples of this in revolutionary situations like Spain in 1936, May 1968 in France, Chile in 1973, and Poland in 1980. In only one case so far did workers succeed in taking power—in Russia in October 1917 through the workers’ soviets. What made the difference in Russia was a revolutionary organisation, in the form of the Bolshevik Party, which was capable of leading the working class to victory.

Even in recent years regimes have been toppled by popular revolutions in countries like Egypt in 2011, and in 2019 in Algeria and Sudan. In Egypt and Sudan in particular, the working class played a key role in bringing down the government. We will need mass struggle on a similar scale to force the changes required to save the planet. The thousands who have already begun to act give us reason to hope.

References

- Ian Angus, Facing the Anthropocene, Monthly Review Press, New York, 2016, p69.

- Richard B. Alley, Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2002 quoted in Facing the Anthropocene p70

- In 2014 US per capita emissions were 16.5 tonnes compared to just 6.4 tonnes for the EU and only 4.6 tonnes in France, which gets most its energy from nuclear power, according to World Bank statistics available at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC?locations=EU-US-FR

- Ross Garnaut, The Garnaut review 2011, p77 http://www.garnautreview.org.au/update-2011/garnaut-review-2011/garnaut-review-2011.pdf

- Clean Energy Council, Clean Energy Australia Report 2019, p70 available at https://assets.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/documents/resources/reports/clean-energy-australia/clean-energy-australia-report-2019.pdf

- ClimateWorks Australia and WWF 2015, A prosperous, net-zero pollution Australia starts today, p10 available at https://www.climateworksaustralia.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/a_prosperous_net-zero_pollution_australia_starts_today.pdf