As part of trying to soften us up for “the economic leadership our nation needs”, Malcolm Turnbull has been telling us Australia is a “high wage, generous social safety net, first world society”. The third claim is unarguable (it’s true by definition), but the stats show that our economic woes are producing wages growth that is anything but high.

Since the end of the mining boom in the middle of 2012, real wages in Australia have gone practically nowhere. Retail workers have seen their real pay per hour excluding super increase inch up by 0.12 per cent per year; real pay in accommodation and food services has grown by just 0.10 per cent per year. These are also the people who rely most on the penalty rates which are currently in the government’s sights. In administration and support services pay actually went backwards slightly.

In fact, across the economy as whole, taking into account super, the average worker is being paid 2.3 per cent less per hour than they were three years ago after adjusting for inflation.

As for the claim that Australia has a generous social safety net, try telling that to someone on Newstart, which, along with its draconian activity requirements, is indexed to CPI and therefore doesn’t increase at all in real terms.

Unsurprisingly under these conditions inequality is getting is worse. The latest figures are for 2013-14, and show that the richest 20 per cent grabbed nearly half (48.5 per cent) of all income. The poorest 20 per cent took home just 4.2 per cent. As Bill Shorten pointed out on Q&A recently, inequality in Australia is the worst it’s been in 75 years.

What Shorten didn’t say was that much of this happened while Labor was in government. Under Rudd and Gillard the Gini coefficient increased a little (from 0.438 to 0.446, where zero is perfect equality and one maximum inequality), and during the Accord years under Hawke and Keating the share of income going to the top 1 percent increased by nearly 40 per cent.

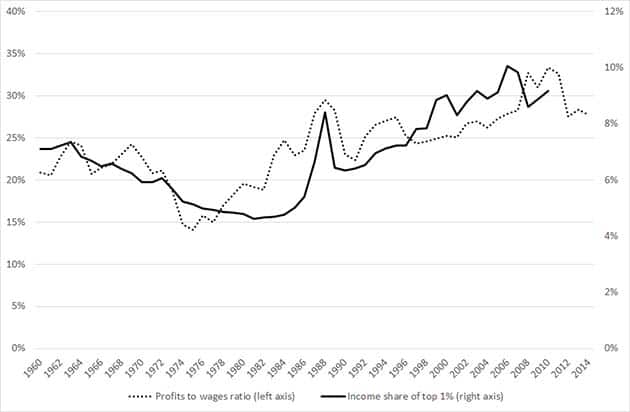

The underlying causes for rising inequality are fairly clear: around the world the ruling class response to falling profit rates from the 1970s was attacks on workers’ pay and conditions. Here this succeeded in pushing up profits (if not the rate of profit) at the expense of wages, as the graph below shows. It compares the ratio of profits to wages with the share of income for the highest 1 per cent of “earners”.1

The data demonstrate a number of things: first, the introduction of superannuation hasn’t meant increased profits now “benefit everyone”, income from company profits and investment properties continues to flow overwhelmingly to the rich. Second, although in Australia the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) didn’t coincide with a significant fall in profitability, it did give bosses a pre-text for holding down real wages. Third, record high prices for Australia’s exports during the mining boom overwhelmingly boosted profits and not wages. Fourth, the decline in the ratio of profits to wages since then still leaves it at around the same level as before the GFC.

The increase in the profit share and inequality is also related to the decline in union coverage and activity. This link is clearest if we look at rates of increase in real wages by sector. Since 1997 (the first year data is available), the weakest growth in wages has been in: information, media and telecommunications (an average annual increase of 0.38 per cent); “other’” services (0.24 per cent); retail trade (0.20 per cent); and accommodation and food services (just 0.01 per cent). These are some of the most poorly organised industries.

On the other hand, the strongest growth in real wages since 1997 has been in industries where unions have suffered smaller declines in density and levels of activity: construction (1.07 per cent per year on average); education and training (1.08 per cent); mining (1.16 per cent); and electricity, gas, water and waste services (1.30 per cent).

The fact that education and training makes this list suggests that union strength has been the crucial variable for determining where wage increases have been won, not so much whether an industry was directly affected by the mining boom. And even though real wages are stagnant on average currently, Melbourne train drivers managed to win a 14 per cent pay increase over four years after taking two strikes, indicating that it is still possible to make gains if the bosses’ hands are forced.

The attacks on the union movement by the Liberals are therefore not primarily an expression of their anti-union ideology, but an attempt to further weaken the institutions which remain the most important vehicles for workers to fight for and win better pay and conditions.

Notes

1. “Profits” here are profits accrued by corporations and landlords after depreciation and company tax, and “wages” include super. Data for the income share of “the 1 per cent” is taken from figures published by the economist (and Labor MP) Andrew Leigh.

By Peter Jones