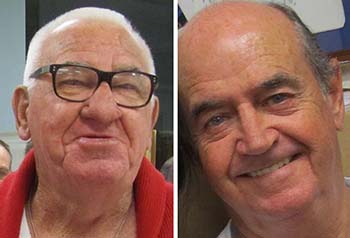

Twenty years ago, during the night of 7 April 1998, Patrick Stevedores sacked its entire workforce in the most serious union-busting effort in decades, with the full support of the Howard government. Solidarity spoke to Bob Lee, a union delegate at Patrick at the time, and Glen Woods, then Deputy Branch Secretary of the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) in Sydney about what happened.

How did the dispute begin?

Bob Lee: I was on my way to work and I heard over the radio that waterside workers had been locked out, dragged from their machines with guard dogs and security and taken off site. I got to work about 5.30am and they were all out the front. They had it well planned.

Glen Woods: Every port that was a Patrick’s port was closed down, they all got the sack.

What were Patrick and Chis Corrigan trying to do when they sacked the 1400 Patrick workers?

Bob: He wanted to do away with the MUA. Unionised labour wasn’t to his liking.

Glen: He also wanted to casualise the waterfront, pay no penalty rates, and have people on call 24 hours a day. He nearly succeeded in doing that after the dispute.

Given the Howard government’s backing for Patrick’s anti-union effort, what would the consequences have been if MUA had lost?

Glen: There would have been no transport workers union, no CFMEU, they would have deregistered all of them. It was a massive win for the MUA to prevent that.

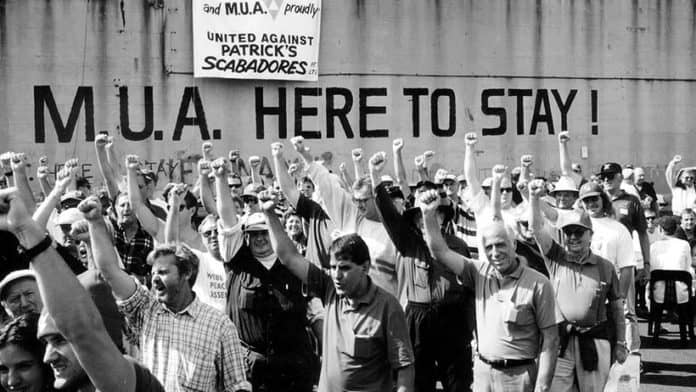

What was the solidarity and support for the MUA like?

Glen: Massive—every union supported the MUA. We had a rally in Sydney on Good Friday that marched from Town Hall to Darling Harbour, and the crowd was still coming down Sussex St into Darling Harbour when the majority had reached the finish. It was enormous.

There was a picket line, a “peaceful assembly” down at the docks 24 hours a day. Someone from another union would run it because MUA officials got subpoenaed off the picket line.

They had a phone tree to contact people and more people would turn up when needed.

Bob: It galvanised young blokes into being the great trade unionists they are today. Because they saw what you could do if you stuck together.

At Port Botany in Sydney, every afternoon, if there was bread left over or cakes the bread shop would bring it to the picket line. The butchers would bring sausages and pies.

How did the workers eventually get their jobs back?

Glen: It went to the Federal Court, and we lost the first case and then we appealed and won and the court said they had to be reinstated. Then the decision was upheld in the High Court.

Bob: But everything was transferred out of one company from Patrick’s no.1 to no. 2 or no. 3. The company still employing Patrick workers was insolvent. Corrigan still had money it was just transferred into a new sham company. They bled the accounts so that nobody could get any money at all. If you had long service leave or annual leave entitlements it was gone.

The MUA had to negotiate with Patrick to get all their annual leave back, their sick leave back, it went on for months and months.

So because Patrick’s sham restructure wasn’t overturned, although the workers were reinstated the MUA then lost conditions?

Bob: They let us go back to work, but working for no pay. I think it’s the first time a company’s been allowed to go back to work when it was in the red and we worked it back into the black. I went to creditor’s meetings to see if they were going to foreclose.

Glen: Because it was a 24 hour cycle out there they’d had a kitchen so you could get a meal. That was gone, there was not even tea and coffee. They tried to make it as hard as they could when you got back in so that you didn’t want to be there.

How did it feel when the dispute was over?

Glen: It was bittersweet. When the dispute was over Bob was one of the “undesirables” who didn’t go back in. There were 12 all around Australia. They said the rest of the workers could come in but we don’t want the union delegates.

Bob: I didn’t get my job back until two months after we went back.

Glen: It changed the whole face of the waterfront, the bosses gained confidence and decided to have a go at people and attack conditions. All the companies changed. But at the end the waterfront was still unionised.

For a full analysis of the dispute see Solidarity’s article written on the ten year anniversary here