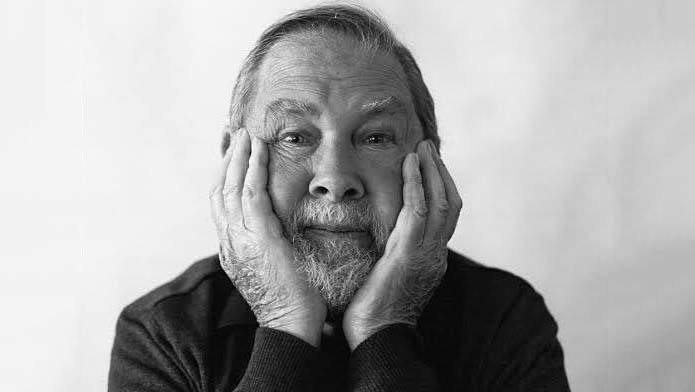

Paddy Garritty was, tragically, one of the too many Victorians this week dealt a death blow by the pandemic. A militant all his life, Paddy was in the Painters and Dockers Union, ran the bar at Trades Hall for many years and had an abiding interest in creative writing and art.

Less well known (not for his lack of talking about it) was how Paddy threw himself into a 1982 unemployment struggle—a campaign that still holds many valuable insights for today’s activists.

1982 and 2020 have two things common—recession and unemployment. These are the only two years since the late 1930s where unemployment has breached 10 per cent.

Unemployment activists today campaign on multiple fronts. They are fighting to lock in the higher coronavirus JobSeeker rate Morrison is cutting next month and planning to abolish next year. New layers of activists are organising to break the neo-liberal chains of Mutual Obligation, Work for the Dole and Robodebt.

In 1982, the full force of neo-liberalism was yet to be unleashed by the Hawke government. Elected in March the following year, Hawke and Keating used the guise of the Prices and Incomes Accord to cut real wages and white-ant union militancy.

In response to rising sackings throughout 1982, the Coalition Against Poverty and Unemployment in Victoria organised a “Stop the City” protest in November. The key to mobilising the 3000 to 5000 who attended was militant labour politics. Twenty-eight trade unions endorsed the rally. The Victorian Council of Social Service and other welfare groups supported the demonstration. Even the Victorian Labor government provided 2000 public transport vouchers for unemployed people to attend.

Crucially, a militant edge was maintained. Tramways Union members let everyone have free public transport that day. Clarrie O’Shea was guest speaker. Jailed in in 1969 for organising illegal industrial action which famously mobilised mass strikes that broke the back of the old laws, O’Shea told the rally, “We have to get out and make revolution to overthrow this rotten system”.

Feisty placards with the old Depression slogans “Work or Riot” and “Eat the Rich” were prominent. A main target on the day was the Melbourne Club. This epitome of ruling class privilege banned women, non-whites and Jews from membership. The crowd stormed the Club while luminaries such as the Dean of Medicine at Monash and Sir Gustav Nossal, director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Science, were having drinks and canapes.

In their second volume of Radical Melbourne, Jeff and Jill Sparrow air Paddy’s recollections of getting into the Club:

I tried the first window, the second window, the third window—when I got to the fourth window I hopped in. By this time, all the crowd’s congregating outside. So the table’s been set, with this lovely setting. So I pick up the champagne glass and start revolutionary salutes to the crowd and toasting them, and they go beserk.

While the demonstration forced the police to release a dozen protesters who managed to get inside, Paddy and three others (including myself) were charged with riot, affray and thousands of dollars in criminal damage. The most costly breakage was in the “ladies guest toilets”—a chandelier ripped down by women protesters.

Class politics was central to Paddy and the rest of us winning our case when it went to trial. One common law requirement to establish the charge of riot is that it causes, “fear in a person of reasonable courage and character”.

In court, the police officer claiming a riot had in fact occurred said he was in fear after seeing a banner with “Eat the Rich” on it. Len Hartnett, one of our barristers, just stared at him, then theatrically turned with his mouth open to address the jury, “Do you mean that you thought the demonstrators were going to eat people?” Hartnett had the jury laughing so hard that one juror had to excuse herself to go to the toilet.

By Marcus Banks