Student debt levels have exploded since HECS fees were introduced 30 years ago, explains Tom Fiebig, as governments have moved to slash spending on universities

Today, a university student will end up on average $20,303 in debt. The size of student debts is rapidly increasing—around 150,000 students now have over $50,000 in debt.

This year marks 30 years since HECS, the Higher Education Contribution Scheme, was introduced, effectively bringing to an end to the short-lived period of free education that began under Labor Prime Minister Gough Whitlam.

In 1974, Whitlam abolished tuition fees and established free tertiary education. He had come into office on the back of the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s, in which university students played a prominent part.

After Whitlam was deposed in the 1975 “Constitutional Crisis” Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser made several concerted attacks on free education.

The first came in 1976, when Fraser tried to re-introduce tuition fees for second and postgraduate degrees. However, despite having control of both houses of parliament, he was forced to back down after an unprecedented national student strike. Banks also refused to implement a commercial loans scheme to underwrite students’ ability to pay. The second attack came in 1982. This time, Fraser was able to introduce fees for international students.

Yet it was a Labor government entering office in 1983 that really ended free education. In the August 1986 Budget, Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke introduced a $250 “administration fee” charged to students on enrolment.

The government claimed this was a small fee that students could easily afford to pay. But it proved to be the thin end of the wedge, as fees multiplied and continually increased in size.

Universities were next allowed to charge international students full fees, covering the whole cost of their courses.

In 1989, Labor introduced HECS, which was designed to make domestic students pay a proportion of the cost of their degrees. The next year, it gave universities the go-ahead to charge up-front fees for some post-graduate courses, and in 1994 it deregulated postgraduate fees to allow universities to charge fees for any course, according “to what the market would bear”.

Labor’s “user pays” model of education was designed to push the costs of university funding more and more onto students in order to cut government spending.

This was part of Labor’s embrace in the 1980s of neo-liberalism and free market policies that saw it hold down government spending in order to cut corporate taxes and boost the profits of big business.

During their time in office the Hawke-Keating Labor governments reduced corporate tax rates from 49 to 33 per cent and cut the highest personal tax rate from 60 cents to 47 cents in the dollar.

This is a model that Labor today continues to support, with the last Labor government under Julia Gillard slashing university funding by $2.3 billion in 2013.

HECS was introduced in 1989 at a flat rate of $1800 per student. It acts as a loan scheme that allows students to defer university tuition fees, and pay them back once they earn an income over a set threshold. The Howard government significantly increased HECS fees in 1997, introducing three separate HECS bands with higher rates for courses like science, law and medicine. Then in 2005 it allowed universities to increase HECS fees another 30 per cent, renaming the system HECS-HELP.

One year of study now costs up to $10,958, so that a standard three year course can easily cost students over $30,000.

Recent changes mean that students starting university in 2019 will have to start paying back HECS sooner, at an income of $45,000, not far above the full-time minimum wage. This is at a time when most students have no hope of retiring or ever owning a home—since house prices have sky-rocketed and wages have stagnated.

International students are also being extorted; the deregulation of fees is seeing them pay up to 400 per cent more than domestic students for the exact same course.

What’s wrong with HECS?

Despite the massive debt burden that HECS places on students, it is common to hear the argument that HECS is a fair system because of the benefit that students receive from their education. Students who complete a degree will generally get a higher paying job, it’s said, so it’s unfair for the government and taxpayers in general to meet all the costs.

Viewing education in individual terms as an investment to the future, they thus conclude: it is only fair that students fork out the cost themselves. But the main benefit of university spending goes to business.

The system of university education was established to fit the needs of Australian capitalism, creating a labour force that has the skills that business needs.

The majority of students end up working as exploited labour generating corporate profits. Businesses require hundreds of thousands of specialists and technicians to operate, and cutting edge research to boost their profits and outcompete their rivals.

Universities historically emerged as bastions of the elite, a space where a privileged minority could rub shoulders and prepare for a life as part of the ruling class or in a small number of elite professions. This is no longer as clearly the case. Nowadays there is a 90 per cent chance that a person in Australia will enroll in a TAFE or university course at some stage during their life.

In the period after the Second World War, universities moved away from being playgrounds for the rich, and began to gradually open up to admit entry to individuals of more working class backgrounds, expanding in two major phases.

This reflected the new needs of Australian capitalism following the war.

In 25 years Australian university enrolments increased from 30,000 in 1950 to just below 300,000 in 1975– a rate six times the rate of population growth.

The second phase of expansion began in the early 1990s. By 2003 more than 920,000, including many overseas students paying full fees up-front, were enrolled in Universities across Australia.

However, the more recent expansion of the University sector was not, in the most part, funded by government. Rather, the funding gap was covered by students and their families, through HECS and full cost-recovery fees.

As student contributions to education costs have increased, the government has been able to cut its own expenditure on education from just over 1 per cent of GDP (national income) in 1983-84 to 0.8 per cent in 2015, well below the average of the OECD group of rich nations. Today, government spending makes up only 40 per cent of total university funding, down from near 100 per cent in the early 1980s.

While many jobs nowadays require applicants with graduate qualifications, in 2015, the median salary for bachelor degree graduates aged less than 25 in their first full-time job was below the median wage—at $54,000—hardly permitting a life of luxury.

Whilst some graduates do certainly enter high-paying professions such as medicine or law, the solution to this isn’t to make the majority of students pay higher fees, but rather to increase income-tax on this minority.

The enormous, and growing, size of today’s average HECS debts is a serious deterrent to students from poorer backgrounds entering university, particularly when a university degree is no longer a guarantee of a job.

Figures from 2017 showed 15 per cent of graduates were still out of work four years after finishing a degree. Added to this is the prospect of at least three years of poverty while studying, given the hopeless level of student income support.

Fight back

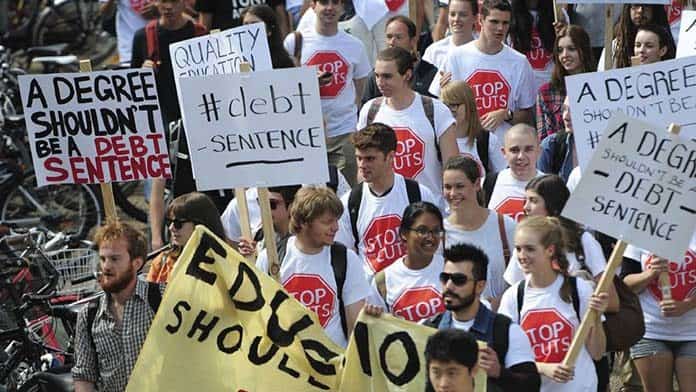

Protests of thousands of students opposed the increases in university fees and funding cuts all the way through. While the student movement has been unable to prevent the introduction of higher fees, activists have succeeded in blunting the neo-liberal agenda.

In 1997 John Howard’s Coalition government introduced full upfront fees for domestic students. University administration buildings were occupied across the country in protest at university managements who decided to implement the fees. The opposition to full fees eventually saw Labor repeal them when it came back into government.

Attempts by the Coalition under Tony Abbott to deregulate fees in 2014 was met by a similar defiance and anger.

Education Minister at the time, Christopher Pyne, planned to deregulate university fees, as well as slash funding by 20 per cent, giving university managements the ability to increase fees as high as they liked. Widespread public opposition, including student protests across all major cities saw the Liberals back down on deregulation, after the proposed changes were defeated in the Senate.

But the corporatisation of universities and their shift away from government funding means that they have become run like businesses in their own right.

For example, the University of Melbourne’s ordinary activities in 2017 alone were enough to generate an income of over $2.2 billion.

The corporate education model gives rise to constant cuts to courses and jobs on campus, and reducing the quality of education through slashing face-to-face contact hours and replacing them with labour-saving online content.

Universities’ income-streams have also diversified to include income derived through private investments (including in companies linked to arms manufacturing, and the fossil fuels industry).

School kids are taking up the cause of protest, planning to leave school early on 15 March for a “climate strike” to demand action on Climate Change.

University Students can take inspiration from this, and previous struggles around education on campus. We need to channel the inspiration into a renewed fightback for more government funding and better conditions on campus, and ultimately for the free and accessible education that we deserve.