The NSW’s Premier’s Literary Awards 2022 Book of the Year, Still Alive: Notes from Australia’s Immigration Detention System, illustrates the horrors and depravity of Australia’s refugee detention system.

In haunting black fine-liner sketches, author and artist Safdar Ahmed tells the stories of some of the refugees he met while visiting Sydney’s Villawood detention centre over more than a decade. The graphic novel is a testament not only to the resistance and resilience of refugees portrayed, whose own drawings are also interspersed throughout, but the power of art and artist-activists in fighting for a better world.

It offers an accessible introduction to the history of successive Australian governments’ cruel treatment of refugees who arrived by boat. However, it unfortunately misses out some important elements of the history of resistance to the policies.

Convention

Still Alive details the history of the term “queue jumper”, which was first applied to the Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees who arrived in Australia by boat between 1976 and 1981. It has since been used by both Coalition and Labor governments to suggest asylum-seekers arriving by boat are “illegal” even though Australia is a signatory of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, which states in Article 31 that refugees should not be discriminated against based on how they arrive.

However, the discourse against “boat people” really took off in the ’90s. The Keating Labor government introduced mandatory detention in 1992. Then in 1996, the Howard government linked the refugee and humanitarian programs, with the punitive consequence that the number of refugees who arrived by boat was subtracted from the number of refugees Australia would accept from those awaiting settlement in a refugee camp. This pitted refugees against each other and gave legal cover to the notion of queue-jumper.

Through the personal and political stories Ahmed weaves through the novel, it vividly demonstrates the reality of the situation: there has never been a queue. Years, sometimes decades, of languishing in poverty await asylum-seekers who can flee to a transit country willing to process their asylum claim.

Currently, some 13,000 refugees live in limbo in Indonesia, a country which can be described as Australia’s informal regional detention centre. They languish there for years without work rights, access to education, or healthcare. Millions of others around the world subsist in UNHCR camps or in states of illegality in transit countries with little to no hope of immediate resettlement.

Still Alive powerfully conveys the real desperation, poverty and lack of alternatives that underlies refugees’ decision to put their fate in the hands of people smugglers. Refugees who are fleeing repressive regimes which refuse to recognise their cultural, religious or LGBT+ identity cannot attain legal identity documentation. Many either lose or are forced to discard documents in the difficult and dangerous journey to freedom and safety.

TPVs

Still Alive’s discussion of the history of temporary protection visas (TPVs) is also significant and timely. TPVs were introduced in 1999 by Philip Ruddock, the Immigration Minister under John Howard. Their introduction followed Ruddock’s embrace of the anti-Asian, anti-refugee racism of One Nation’s Pauline Hanson.

In her infamous 1996 speech Hanson declared that “we are in danger of being swamped by Asians”. She argued that refugees should be granted only TPVs, on the basis that these make it easier to deport them. Ruddock consequently introduced TPVs, which prevented family reunions and travel outside of Australia.

The Albanese Labor government’s commitment to abolish TPVs and grant the estimated 19,000 TPV holders with permanent visas is a significant step forward. At the same time, it offers no solution to the estimated 10,000 refugees currently in the community on poverty inducing bridging visas. Deliberate government-ordered processing priorities means that family reunion applications are essentially restricted to citizens.

Offshore detention

Still Alive also portrays the serious uptick in anti-refugee racism under Howard in the lead up to the 2001 election. Howard used the tragedy of the mass drownings when the boat known as SIEV-X sank to turn public sentiment against refugee boat arrivals.

The Tampa affair saw Howard refuse entry to the Norwegian vessel the Tampa carrying hundreds of asylum-seekers. He had emergency laws passed to excise Christmas Island and other coastal islands from Australia’s migration zone, preventing boat arrivals landing at those islands from applying for refugee status. This laid the ground for years of brutality against refugees, sharpened by islamophobia from politicians and the media following 9/11.

Still Alive suggests an uninterrupted continuity between Howard’s Pacific Solution Mark I and the Pacific Solution Mark II instituted by Labor’s 2012 Rudd government. Howard is pictured declaring: “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.” Rudd is pictured later introducing Pacific Solution Mark II: “From now any asylum-seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees.” July 19 this year marks the ninth anniversary of this declaration.

However, this narrative of uninterrupted continuity misses the short period (2008-2012) in which offshore detention was not in place. By blurring this history into one continuous, uninterrupted stream of bipartisan government anti-refugee racism, Still Alive misses two key lessons:

- Offshore detention under Howard was brought down by a mass protest movement.

- Demobilisation by this movement allowed it to be resurrected.

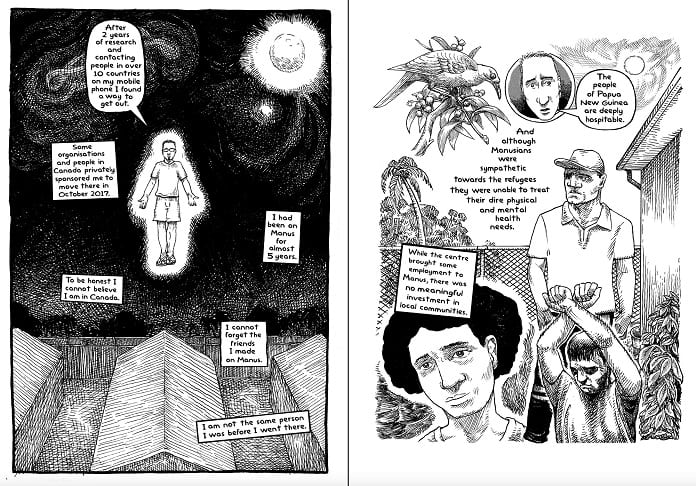

The political demobilisation of the refugee movement after the 2007 election allowed Labor to resurrect the whole rotten deterrence-regime architecture. Still Alive portrays in graphic detail many of the horrific events which followed: the establishment of the Manus and Nauru camps, the murder of Reza Berrati in Manus, the Nauru Files, the Manus Siege and the death of Hamed Khazei from septicaemia.

Still Alive reveals how the entire detention/deterrence regime has—from its beginning—tried to brutalise and destroy refugees. Its function and legal basis has been perfected by consecutive Liberal and Labor governments. The current Labor government may present offshore detention as simply “administrative” and attempt to provide a humanitarian cover for boat turnbacks, but this belies the inherent cruelty both involve.

Resistance

The novel finishes with depictions of protest and different forms of resistance by refugees. It shows the courage, resilience, and humanity of refugees despite everything, as well as the therapeutic and political power of art and music. The author of Still Alive ends on a defiant and hopeful note with a call on readers (and himself) to do what we can to change the world.

The resistance by refugees inspires the refugee movement’s struggle and political demands. However, going by Still Alive’s presentation, readers might be excused for thinking that a domestic refugee movement in Australia doesn’t exist.

In its desire to convey the brutality of detention, Still Alive omits any mention of the myriad of small but significant wins helped brought about by the refugee movement.

I would have loved to have seen pictured the heroic blockade of nurses and healthcare workers at Lady Cilento Hospital in Brisbane that prevented the deportation of Baby Asha. Or images of teachers in Victoria and Queensland walking out of schools in the hundreds to force Scott Morrison to bring all the children and their families from Nauru to Australia.

A panel could easily have been dedicated to the more recent large and sustained protests at the Mantra and Park hotel prisons in Melbourne or Kangaroo Point in Brisbane, which forced the release of almost all Medevac refugees around the country.

It’s only by recognising where these victories came from that the movement can effectively move forwards and build the basis for more profound change.

By Tom Fiebig

Still Alive: Notes from Australia’s Immigration Detention System, by Safdar Ahmed

Twelve Panels Press, $30