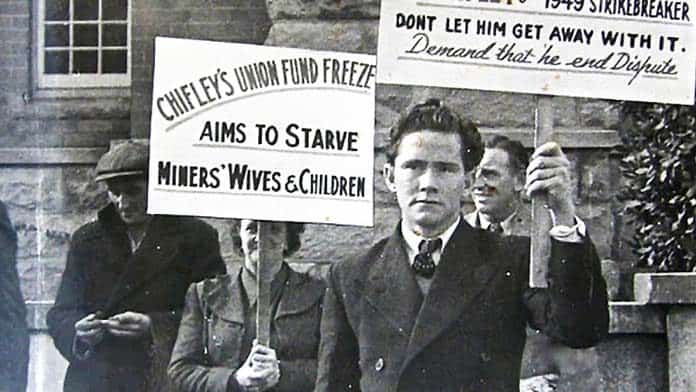

Even in its supposed golden age, a Labor government was prepared to use all the tools at its disposal to wage war on unionism and break a strike, writes David Glanz

Even today, Prime Minister Ben Chifley remains a totemic figure within the Labor Party. It was he who coined the inspirational Labor slogan, the Light on the Hill, pointing the way to a better society.

He had taken part in the NSW general strike of 1917 as a train driver.

Yet in 1949 he was responsible for one of the greatest betrayals of Labor in government—sending in the army to scab on a coal miners’ strike in NSW.

The years immediately following the Second World War were pregnant with radical possibilities.

Worldwide, millions had died, tens of millions more were wounded or displaced. Europe was in tatters. Workers on the home front had been cajoled or coerced into heroic feats of production.

They had also suffered enormous privations in peacetime, in the Depression that preceded the conflict.

Australia was no exception. Unemployment peaked at about 30 per cent in the 1930s. Some 40,000 Australians died in the war and those at home were made to sacrifice, through rationing of essential goods and inflation.

The mood in 1945 was that it was time for workers to get their reward.

The first to gain from this was Labor under Ben Chifley, returned with 49.7 per cent of the first preference vote in the 1946 election—one of its best ever results. It held 33 of 36 senate seats.

But workers quickly found that improvements would still have to be fought for.

Chifley opposed calls for wage increases to compensate for wartime sacrifice. Unionists responded with strike action—four million days in 1945-46 alone—and won substantial gains.

Labor’s obstruction continued over the move to a 40-hour week. Again it was mass action that tipped the balance. The Arbitration Court, in granting the claim from January 1948, declared:

“This working class claim has been and is the basis of industrial dispute and unrest … No realist for a minute thinks that a rejection by the Court in these cases would bring about industrial harmony and would abate for an instant the demand for the shorter week.”

The 40-hour week raised the question of a five-day week with penalty rates for weekend working. Railway workers led the charge in February 1948.

Once again they faced resistance from Labor. Queensland premier Hanlon banned picketing. Police baton-charged a demonstration, injuring several people.

Communist Party of Australia

Central to this union struggle was the Communist Party, which emerged from the war (in which Russia had been an ally of the West) at the peak of its success.

It had 23,000 members, an MP in the Queensland parliament, control of some local councils and, crucially, the support of between 25 and 40 per cent of unionists.

By 1948, many of its middle-class, wartime recruits had fallen away. But the party still had some 300 top-level trade union officials and control of key blue-collar unions.

In 1949, the CP leadership of the Miners Federation decided to launch a three-pronged claim, for a 35-hour week, long service leave and a 30-shilling ($3) a week pay rise.

Chifley blamed the CP for orchestrating the strike as part of a plot against the Labor government.

The truth was that the miners were overwhelmingly behind the strike. They had a proud and militant tradition to draw on. Many of the older miners well remembered the death of Norman Brown—shot by the police on the picket line at Rothbury in NSW in 1929.

They also remembered that 1929 had been a lock-out by the employers and that the state had lined up with the bosses.

As one miner put it in the Newcastle Morning Herald in July 1949: “I have no doubt that the conditions I enjoy today are the direct result of the struggle and hardships of the past …

“We will continue to use our gifts in the only way we ever have found to get results—by struggle.”

Miners backed the claim and the call for a general strike by 7995 votes to 822. Their union paper, Common Cause, reported that meetings were, “among the best in the Federation’s history … with a higher attendance and better vote that those on the eve of the big 1940 general strike”.

It was the employers who used deliberately provocative tactics in the run-up to the strike.

They not only rejected the pay claim and the 35-hour week, but called on the Federation to make four significant concessions in return for a watered-down long service leave clause.

In June, the Federation was poised to call mass meetings for action. When the head of the Coal Industry Tribunal indicated that the union’s claim would be “generously” considered, the leadership postponed the meetings for a fortnight.

Far from accepting this olive branch, the employers announced that they would oppose long service leave outright.

It was this, much more than any “Communist plot” that tipped the balance towards striking.

The dispute was a turning point that shaped Australian politics for a generation.

On their side, the miners had the power that comes from stopping coal supplies in a society dependent on the stuff. Industry ground to a halt.

While the miners also enjoyed widespread solidarity, they found they were up against not just the employers, but the state.

Labor attacks

Labor launched a series of vicious attacks on the miners and their supporters. Immediately after the strike began they banned strike pay and solidarity donations—even making it illegal for shopkeepers to extend credit.

On 5 July, union officials were ordered, under threat of imprisonment, to hand over union funds to the industrial registrar.

They responded by withdrawing a large amount of money from the bank to avoid it being seized.

At the same time, the High Court rejected an appeal by the unions. On 6 July, union officials were arrested. Two days later, union and CP headquarters were raided.

In the last week of July, seven union officials were sentenced to 12 months’ jail and one to six months. The court also imposed fines on another five officials and three unions (the Miners Federation, Waterside Workers Federation and Federated Ironworkers Association).

Alongside this repression, Chifley deployed some new tactics, such as major advertisements in the papers putting the government’s case, as well as a dirty old one—convincing the rail union to scab.

Labor MPs went into the coalfields and into major workplaces to argue with the miners and their supporters head on.

The tone deteriorated. The Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, told tens of thousands in the Sydney Domain that Communists should be put into concentration camps—just four years after the Holocaust.

He continued: “We will use all the resources of the country against them. We will use the army on them, the navy on them and the air force on them …

“Only the stars are neutral in this fight. This is a fight between the Labor movement and the Labor Government on the one hand and the Communist ratbags on the other. It is a fight that the Government must win …

“The army will be used in the open cuts. We will run up the Australian flag and it will cover Australian servicemen mining coal in Australia for the Australian people.”

By 1949, the Communist Party’s analysis was that a recession, even a Depression, was coming and that workers should grab what they could before the going got tougher.

The CP had also sharpened its anti-Labor rhetoric and was counterposing itself to the ALP in an increasingly shrill, ultra-left way. But there is no indication that it was planning for insurrection, as some have claimed.

After five weeks, Chifley sent in 2500 soldiers to work the mines. It was the first use in peacetime of the army against a strike. Within another two weeks, the strike was broken.

Far from bringing down capitalism, the outcome of the strike weakened the Left for a generation. The CP went into what turned out to be a long, irreversible decline.

Labor lost the December 1949 election. The strike was not the only reason—Chifley’s pledge to retain rationing in order to help Britain was also deeply unpopular.

The result was not only an even more rabidly anti-Communist government under Menzies, but the deepening of anti-Communism within the ALP, leading to the 1955 split.

The story of the 1949 strike is more than a historical curiosity.

For many Labor supporters even today, the 1940s was the party’s golden age. Curtin presided over the establishment of the Commonwealth Housing Commission, brought in a new tax system and introduced the widows’ pension and unemployment and sickness benefits.

But when bosses’ profits came under attack—and coal was even more central to the economy then than it is now—the ALP turned to vilification, repression and the threat of outright violence.

The dynamic of the strike shows the depth of Labor’s loyalty to the system. It shows how Labor will fracture its base rather than threaten capitalism.

Seventy years on, it is inconceivable that a Labor minister would stand on a soap box and talk directly to striking workers.

But it is sadly all too believable, if the stability of the system demanded it, that today’s Labor would wield its biggest sticks against us.