Tom Orsag looks at the bitter class struggles ignited by the First World War in Broken Hill, in the first of a Solidarity series on war and workers’ resistance

A Labor government was elected as the First World War began just over 100 years ago in 1914. It held down workers’ living standards and enthusiastically backed the war for the British Empire. By 1916, Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes was campaigning for conscription.

This produced an enormous clash with trade unions and the left, who won stunning victories both industrially and against conscription.

Two of the stand-out individual leaders of these campaigns were Jack “Percy” Brookfield and Mick Considine—both from tiny Broken Hill, in far western NSW.

Both were miners, militants and union leaders who became Labor MPs. Percy Brookfield, a NSW MP, has been better remembered, following his tragic death while trying to disarm a deranged gunman in 1921.

Mick Considine became the Labor MP for the now abolished federal seat of Barrier.

Broken Hill was then the third largest city in NSW and its rich silver and lead deposits gave rise to BHP (originally the Broken Hill Proprietary company).

Its large mining workforce produced strong unions and made the town a magnet for socialists and class conscious workers.

The Labor government promised to defend the British Empire in the war “to our last man and our last shilling”. Labor, like social democratic parties around the world, capitulated to its own ruling class to support the slaughter.

Australia entered the war outwardly united. Class and sectarian differences were blanketed by an initial jingoistic patriotism.

A level of anti-German hysteria developed. There were nine recorded strikes where workers refused to work alongside German-Australians.

Broken Hill was little different. The mining industry in NSW accounted for three-quarters of all strike days in the years before 1914.

However, at a conference convened by Broken Hill mining companies a fortnight after the war began, union leader W.D. Barnett, head of the Amalgamated Miners Association (AMA), promised to support the war effort, telling bosses, “We are going to give you every assistance … anything we can do in our power to get work carried on at Broken Hill.”

The German Club in Broken Hill was burnt down on New Years’ Day 1915. In that year the number of strikes fell by 50 per cent.

But the socialists and militants of Broken Hill refused to give up the class struggle because of the war.

Eventually, the scale of industrial scale slaughter as well as the impact on the cost of living eroded working class support for the war.

In NSW, prices rose by around 30 per cent between 1914-1917, even as wages fell. On the other hand the federal government offered profitable interest rates to the wealthy who could afford to loan it money for “war bonds”. The stark class divide would fuel bitter class conflict.

Barrier miners’ breakthrough

Thousands of miners lost their jobs as the war began, with Germany the Broken Hill mine’s main export market. But by early 1915 employment had recovered as demand for the war effort inflated the value of commodities used in munitions and armaments.

In March 1915, with the miners’ contract due to expire, they demanded shorter working hours and more pay. Mine owners wanted the same contract in place until six months after the war ended.

In May, a motion to strike for a 44-hour week was defeated at a mass meeting due to continuing pro-war sentiment.

But over time the companies’ efforts to cry poor wore thin due to rising metal prices and profits.

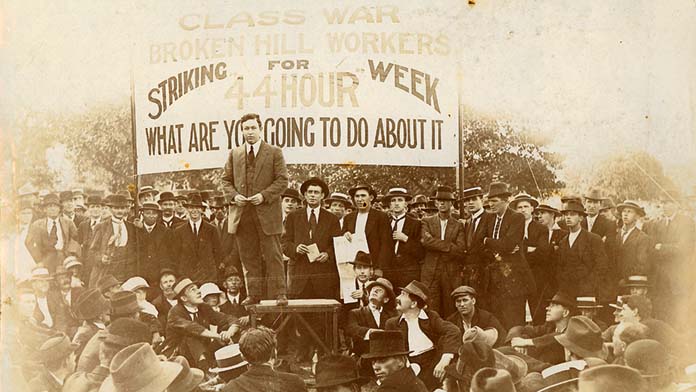

By late September, anger boiled over, with a mass meeting of underground miners resolving to boycott the Saturday afternoon shift and to work only a 44-hour week.

At an Eight-Hour Day march, thousands of workers wore badges saying “If You Want a 44 Hour Week—Take It.”

Underground workers, including Brookfield, were determined to carry on the fight. The less militant surface workers, including Considine, abandoned them.

In response, the companies sacked all the underground miners.

Even though Considine had opposed the strike, he responded in a principled way to the companies’ escalation of the dispute. “All that was a thing of the past … It is now a question of the mining companies versus the workers of the Barrier.”

A mass meeting declared a strike of all 3000 workers from 11 companies.

The NSW Labour Council refused to back them. But the miners held out despite being branded “German sympathisers” and won.

The Arbitration Court, under orders from the federal government, awarded underground miners a 44-hour week in April 1916.

The victory in Broken Hill began a wave of strikes nationwide demanding pay rises in the face of rapid inflation. Some also won a 44-hour week including miners at Gympie in Queensland.

In November 1916, coal-fields districts across Australia went on strike, overturning a compromise by their officials. They won a smashing victory of a 15 per cent wage increase and shorter hours. The strike wave kept spreading.

By 1916, Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes wanted conscription, with enlistment falling as enthusiasm for the war waned. Faced with deep opposition in the Labor Party and the unions, he called a referendum—or technically a plebiscite—for late October 1916.

Hughes hoped that a vote in favour of conscription would silence his opponents. But with anger growing at the cost of the war on living standards and the government’s failure to fix prices, the move saw the tensions between the government and its base in the unions and the Labor Party explode.

In four states, Labor Party conferences declared against conscription by overwhelming majorities. These decisions were backed up resolutions of the Labour Councils in every state and a special Australia-wide trade union conference.

In Broken Hill, the mining union’s paper, the Barrier Daily Truth, initially took a pro-war stance in 1914.

A small minority of socialists and radicals like Considine and Brookfield, alongside the Australian Socialist Party and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), opposed the war from the beginning. By 1916 they were leading thousands.

In Broken Hill the referendum led to street battles between supporters and opponents of conscription. In July 1916 anti-conscriptionists launched an organisation called Labor’s Volunteer Army, with Brookfield as president.

Members declared that “the conscription of life and labour in Australia will be a death blow to organised labor and will result in the workers of this land being crushed into subjection by a capitalist military oligarchy”, as part of a pledge to fight conscription and defend unionism.

More than 2000 draft-age workers enrolled.

In August, Empire loyalists attacked an anti-conscription speak-out. Brookfield was pelted with eggs and tomatoes as he tried to speak, then assaulted and beaten.

The next night 10,000 people rallied in the town of 30,000 to denounce the attack.

The government made ruthless use of wartime powers to suppress opponents of conscription, censoring newspapers and prosecuting more than 3000 people nationwide including Brookfield for speeches deemed “prejudicial to recruitment”.

Twelve members of the IWW in Sydney were jailed for up to 15 years on trumped-up charges of arson.

Conscription was defeated by 72,000 votes Australia-wide. The decisive state was NSW, where the majority for “No” was 120,000. In Broken Hill, 70 per cent voted “No”.

Labor’s crisis

Conscription tore the Labor Party apart. Prime Minister Hughes was expelled from the party. NSW, Victorian and Queensland Labor branches issued an ultimatum to all MPs to oppose conscription or lose the right to stand as Labor candidates.

In Broken Hill, Considine and Brookfield campaigned against the “old generations of [Labor] politicians, whose flirtations with the vampire [the capitalist] are so openly admitted by the latter’s press”.

Both the local federal and state Labor MPs, Josiah Thomas and John H. Cann, were prominent supporters of conscription.

The result was that in 1917 Brookfield became the state Labor MP and Considine the federal Labor MP for the seats based on militant Broken Hill.

Hughes joined with the conservatives to form a new Nationalist Party and retain government. He then called a second plebiscite on conscription—and was defeated with an even bigger majority.

Both Considine and Brookfield used their positions in parliament to campaign vigorously for the release of the IWW Twelve from prison.

Brookfield was so incensed by Labor’s inaction that he resigned from the party in disgust. He was re-elected to parliament as part of a breakaway Industrial Labor Party formed by militant unionists.

Considine was re-elected as a Labor MP, despite being jailed for three weeks after he refused to pay a fine for insulting the King. A returned soldier called Considine a “bloody Sinn Feiner and disloyal”. Considine replied, “Bugger the King, he is a bloody German bastard.”

He was briefly the acting consul for the new Bolshevik Government of Russia after Peter Simonoff, its official representative, was arrested under the War Precautions Act and jailed.

He too eventually left the Labor Party in 1920 after refusing to condemn his comrade Percy Brookfield for running against it in the NSW election.

Labor tacked to the left in an effort to contain the left-wing radicalisation of the working class as a result of the war and the Russian Revolution, adopting a vaguely worded “socialist objective” in 1921 following the vote of a trade union conference for “the socialisation of industry, production, distribution and exchange”.

This was designed to undercut support for the challenges to its left, including Considine and Brookfield’s Industrial Labor Party and the newly formed Communist Party.

Considine’s parliamentary seat was abolished in 1922 and he failed to win re-election. Unwilling to join the Communist Party, he rejoined Labor—but the party refused him pre-selection ever again.

The experience of Broken Hill was part of a wave of the class struggle that showed how war can lead to mass strikes and workers’ radicalisation—and rank among the high points of workers’ struggle in our history.