It was the radical politics of the Gay Liberation movement that emerged from Stonewall that set in motion the shift in attitudes on LGBT rights, explains Amy Thomas

On a hot June night in New York in 1969, hundreds of LGBT people and their supporters rioted after a police raid on the popular gay nightclub, the Stonewall. Why talk about it today?

While Australia’s parliamentarians can’t bring themselves to put and pass a bill for equal marriage, their conservative obstinance bucks the general trend.

The US became the twenty-first nation to legalise same-sex marriage in June, and Ireland the first nation to do so by popular vote not long before. Many Western leaders have recently, and reluctantly, come to accept the inevitably of same-sex marriage.

Just less than 50 years ago, life as an open gay or transgender person in countries like Australia or the US was nearly impossible.

Stonewall, and the Gay Liberation movement that emerged out of it, changed all that. It is to that radical legacy we owe our advances, and to that legacy we can look to see why, even with equal marriage, LGBT equality will be incomplete.

The stage

The situation in Australia and the United States in the 1950s and 1960s for LGBT people was broadly similar. Post World War II, there was a crackdown on homosexuality as part of a drive to reconsolidate the nuclear family.

All over the US, sodomy was illegal, and there were no legal protections against discrimination on the basis of sexuality or gender identity. Men were regularly entrapped by police in “beats” (places where men would go to have sex or be with their male partner) and arrested.

An arrest could ruin your life; your name could be published in the paper, you could lose your job, your home, and your family, you could be jailed or committed to a psychiatric hospital.

Gays were prohibited from working in the public service or schools. Alongside this ran titillating tabloid exposés that described homosexuals as wrong, deviant, sick, criminal—and even Communist!

For “transvestites” (the language of the time), drag queens or butch lesbians, there was another risk in New York—it was illegal to wear less than three pieces of clothing that matched your sex. Police would physically examine people they suspected of gender bending.

Yet ironically the increased media coverage publicised LGBT hangouts and so helped subcultures develop in a few major cities, such as in New York’s Greenwich Village. Here, some of the most down-and-out young LGBT people, left homeless by homophobia, created a life for themselves on the streets.

Some gay venues operated, but the situation was volatile and dangerous because a law in New York meant that if a bar served one “known homosexual”, they could be declared “disorderly” and closed down. In the absence of legal bars, the Mafia stepped into the breach to exploit the situation.

The Stonewall was opened in 1967 by three mobsters who invested such a small amount of money and charged so much for their watered-down drinks that they made back their whole investment on the first night of business. They regularly paid off the cops, who would routinely raid the bars to give the appearance of doing something.

Of course, those who paid the highest price for the raids were the customers. But at the Stonewall, you could dance, and kiss, and hold hands, so it quickly became the most popular gay bar in New York.

This was happening at the same time as mass social movements were shaking the world. During the Prague Spring and the French May in 1968, workers and students had brought nations in the East and West respectively to the brink of revolution.

In the US, the civil rights movement had been marching for nearly a decade when Martin Luther King was shot and killed in Memphis. The Black Panthers, an armed, revolutionary black organisation, had formed earlier in the year, tapping into a mood of anger and militancy with their rejection of non-violent resistance.

Alongside black politics, the Vietnam War was a defining issue for a generation. Student occupations, like that at New York’s Colombia University, had exposed links between the education system, the state and the war machine, while hundreds of thousands had marched against the war.

For a lot of young radicals, the intensity of police violence against peaceful protests at the Democratic Party Convention in August 1968 in Chicago changed their lives and their perception of the world.

Some of those who danced at the Stonewall had been at Chicago, dodged the war draft, marched for civil rights or joined the first demonstrations of the second wave women’s movement, or knew someone who had.

It was only a matter of time before these radical ideas began to extend to sexuality and gender identity.

The raid and riot

The raid on the Stonewall on 28 June, 1969 has been described as routine—and mostly it was, except that the police had notably stepped up their efforts and five other bars had been shut down for good that month. And it followed a riot at the Stonewall only the night before.

The police sent in four undercover female officers, followed by four other police who entered, turned on the lights and demanded everyone get to one side. They separated the transvestites, to examine them.

Almost immediately, there was trouble. Some bar-goers talked back. Some transvestites had to be forced into the bathroom for their examination.

Police began to release those with ID—but instead of leaving, the patrons gathered out the front. They began to discuss the raid the night before, and their anger. They began to cheer as their friends were released, one by one.

The police were confused by the situation. Later, the officer-in-charge reflected, “Usually, everybody disappeared. Instead of the homosexuals slinking off, they remained there, and their friends came. It was a real meeting of the homosexuals.”

The police got rougher as their vans arrived, and they began to roughly shove their arrestees in. One transvestite took the imitative and smacked a man-handling officer in the head with her purse, and got a fierce clubbing in return. The crowd booed and refused police orders to move back.

And then it really started. Historian David Carter recounts that, “the next patron to be taken was a lesbian, and she was decidedly not in a good mood”. One woman described, “Everything went along fairly peacefully until a dyke lost her mind … kicking, cursing, screaming and fighting.” A police officer hit her in the head with his club for talking back. So she began fighting back. It took three or four policeman to put her in the van—but after her second, valiant escape, she pleaded with the crowd, “Why don’t you guys do something!”

The crowd surged in, yelling, throwing coins at the police cars, trying to overturn the police cars before they sped away.

Terrified of a crowd of hundreds of homosexuals surging towards them, the police retreated—they went back into the Stonewall and barricaded themselves inside. The crowd went wild. One man explained the feeling of victory in the documentary Stonewall Uprising, “We, the lowliest of the low, had forced them into retreat.”

Many accounts say it was black transgender activist Marsha P Johnston who, at this moment, threw the first brick.

Then the crowd, which had grown to at least a few hundred at this point, began throwing everything they could at the Stonewall—trash cans, cobblestones, bits of wood and bricks, objects on fire. Then a parking meter was up-ended from the street and used to ram the door repeatedly.

A participant, Michael Faber, describes the breakthrough moment this way:

“We all had a collective feeling like we’d had enough of this kind of shit. It was just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head on that one particular night in the one particular place … Everyone in the crowd felt like we were never going to go back. It was like the last straw … mostly it was total outrage, anger, sorrow, everything combined.

“It was the police doing most of the destruction … we felt that we had freedom at last, or freedom to at least show that we demanded freedom … we weren’t going to be walking meekly in the night and letting them shove us around. There was something in the air, freedom, a long time overdue, and we’re going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom like was, we’re not going away. And we didn’t.”

The police eventually got reinforcements and escaped the Stonewall. But they had an extremely rough night. For hours on end, young people outwitted the police on the streets. Some formed up kick lines in front of riot police, taunting them, chanting and singing songs like, “We are the Stonewall girls, we wear our hair in curls, we wear no underwear, we show our pubic hairs”.

Chants of “gay power” and “we want freedom” rang through the streets. Others yelled “We are the pink panthers!” Once the genie was out of the bottle, it couldn’t be put back in. The riot continued on the following night, and then again, two nights later. Support grew, with student activists, the Black Panthers and others joining the fray.

It was a real “festival of the oppressed”, with unity between LGBT people, radical activists, Blacks and Puerto Ricans. The demonstrations were infused with a new spirit of open, public pride in defiance of homophobia.

Gay Liberation is born

Activists saw history unfolding and seized the initiative. A leaflet, “Get the mafia and the cops out of the gay bars”, was distributed by activists the day after the raid, followed by another titled, “Do you think homosexuals are revolting? You bet your sweet ass we are”.

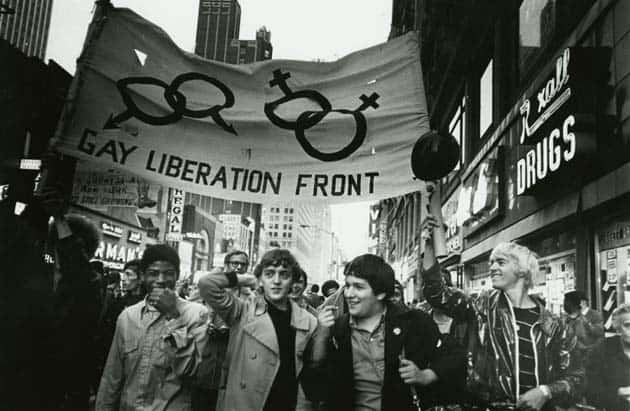

Within a few weeks, the Gay Liberation Front—named after the National Liberation Front fighting the US in Vietnam—was formed.

The group described themselves this way: “We are a revolutionary homosexual group of men and women formed with the realisation that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished.

“We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature. We are stepping outside these roles and simplistic myths. We are going to be who we are … society has fucked with us. We, like everyone else, are treated as commodities. We’re told what to feel, what to think … We identify ourselves with all the oppressed: the Vietnamese struggle, the third world, the blacks, the workers … all those oppressed by this rotten, dirty, vile, fucked up capitalist conspiracy.”

And so began a movement. They produced a newspaper, Outcome, held street demonstrations (a record 2000 people marched one year after Stonewall in the first ever gay Pride march), protested against profiteering gay bars, homophobic media, and stalked bigoted politicians. Inspired, gay liberation movements formed around the Western world.

The results and prospects

Despite the political confusions that would first split the movement then contribute to its decline, Gay Liberation achieved several things. The most important was to reject a quiet, polite approach of appealing to oppressors and instead stand up to them through proud resistance and struggle.

Many activists emphasised solidarity between the oppressed, and saw unity as necessary to victory. Gay liberation groups took banners to demonstrations against the Vietnam War and for abortion rights and gave donations to the Black Panther Party.

This approach won them supporters across the movements for change. Black Panther leader Huey Newton said at the time that “homosexuals are not given freedom and liberty by anyone … they might be the most oppressed people in the society”.

The pre-Stonewall gay rights movement, called the homophile movement and organised around a group called the Mattachine society, had focused on lobbying and presenting homosexuals as respectable by conforming to gender norms.

Gay Liberation’s uncompromising stance radically challenged societal perceptions and started an immense transformation in social attitudes that reverberates still.

They picketed psychiatrist conferences with the slogan, “It’s not me that’s sick but the society that calls me sick”, and won the removal of homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental illnesses in 1973.

Crucial rights, such as anti-discrimination laws, and the right to employment, jobs in schools, and so on, were won by Gay Liberation movements in the Western world.

They were concerned however, not just with simple reforms, though they demanded those, but with liberation and revolution. Some began to identify the heterosexual nuclear family and gender roles as oppressive structures that benefited the state and capital.

However, the movement was divided between those who saw revolution as about fundamental social change, and those who wanted to focus on simply living the change in their own lives.

Alongside this, versions of identity politics that argued men, women and other oppressed groups must organise separately to each other caused strife, and the movement split into smaller and weaker fragments.

And the movement’s very success also opened up the space for gay capitalism and official, conservative LGBT politics.

Pride parades are now mainstream and corporate events, a demonstration of major companies competing for the profits to be extracted out of the LGBT market (like the ANZ bank and their famous Mardi Gras “GayTM”). Those complicit in LGBT abuse, like the police force and government agencies, are regularly invited to participate and sometimes even run such events.

Stonewall itself has been made safer for mainstream politics. It is the subject of a blockbuster feature film, to be released in Australia later this year. The trailer features Barack Obama’s 2013 speech celebrating Stonewall as a crucial moment in the struggle for civil rights.

Many mainstream LGBT organisations—including a UK lobby group called, ironically, Stonewall, and the group Australian Marriage Equality—confine their activities to lobbying for piecemeal change.

It is common to hear that same-sex marriage is the final step to achieve full equality.

But formal legal equality and liberation are different things. The experience of formal equality so far shows that while the changes have been very important, benefits have been distributed unequally, meaning the most disadvantaged, who fought the hardest in many of the struggles, have benefited the least from formal equality while economic equality remains elusive.

It’s one thing for Penny Wong’s partner to have the right (to pay) to access IVF treatment, quite another for a homeless transgender person to contend with a hostile world in the context of a shrinking welfare state and the under-funding of health and education.

The oppressive structures of the nuclear family and gender roles may have taken a battering, but they live on as crucial elements of modern capitalism.

A recent study by BeyondBlue, reported on ABC Radio’s AM program, “found that 40 per cent of teenage boys felt ‘anxious or uncomfortable’ around same-sex attracted people, more than a third wouldn’t be happy to have a gay person in their social group, and a quarter felt it was okay to use the term ‘gay’ as a derogatory term.” Rates of suicide and homelessness among young LGBT people are far, far too high—an indicator of how far we have to go, even while we celebrate how far we have come.

Note: This account of the riot relies heavily on David Carter’s seminal study, Stonewall: the riots that sparked the gay revolution