With Barack Obama set to accept the Democratic nomination for president in Denver on August 28, Mark Goudkamp looks back on the turbulent events surrounding the 1968 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago

During this year’s primaries race between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, some commentators suggested that the enthusiastic response to Obama’s rhetoric of “hope” and “change” reveals a leftward shift in US society not seen since the late 1960s, when a cocktail of the radicalising black civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War coalesced with a revolutionary upsurge in Europe.

This year’s Democratic Party Convention in Denver, Colorado will mark 40 years since the 1968 Democratic Convention, which was marred by scenes of a brutal police crackdown on anti-Vietnam War protests outside.

This repression of a peaceful anti-war protest in the heart of the “free world” took place just a few weeks after Russian troops had crushed the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia and led many people to draw parallels between the two events. The radicalisation this sowed fed into what had already been a tumultuous year in the US.

Vietnam

By 1968 the movement against the Vietnam war had reached mass proportions, polarising US society and creating serious headaches for the government’s war effort.

In late January 1968, the Vietnamese resistance movement, the Viet Cong, launched a major military offensive against the US occupation known as the Tet Offensive. The US eventually succeeded in defeating it in purely military terms, using half a million troops and enormous firepower.

But it was a symbolic triumph for the Viet Cong, proving that they had the overwhelming support of the Vietnamese population. It shook US society from top to bottom from its belief in its own invincibility and showed the lie in continual statements made by the commander of US forces in Vietnam, General Westmoreland, that there was “light at the end of the tunnel”.

As the realisation sunk in that the Vietnam War was unwinnable, US public opinion turned so that a majority opposed the war for the first time.

Four years earlier, Lyndon B Johnson had won the 1964 Presidential election in a landslide on the basis of being the “peace candidate”. Many on the left like the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), later a key player in the anti-war movement, had called for a vote for Johnson as the “lesser evil”. Yet within months, Johnson had significantly escalated the US’s war in Vietnam, eventually sending 550,000 troops. The Democrats had unleashed what would end up costing 58,000 US and around three million Vietnamese lives.

By 1967, the anti-war movement was growing rapidly. In October, 100,000 marched on the Pentagon-until then the largest anti-war demonstration in US history.

The convention

Anti-war activists approached the 1968 Democratic convention in different ways. Supporters of Eugene McCarthy, a candidate for the Democratic nomination for president who had drawn support because of his stand against the war, were central to the initial calls to mobilise in Chicago. Many had genuine hopes that a large presence might influence proceedings inside the convention.

The newly formed Yippies (a counter-culture protest group led by Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin) and anarchist group Up Against the Wall invited people to the city for a carnival-style celebration of protest. The Yippies brought a pig, “Pigasus the Immortal”, into the city to be “nominated” for President. However, as the convention drew closer, and the atmosphere of repression deepened, the tone of the protest became much more serious.

Democratic Party politics in Chicago was dominated by the city’s mayor, Richard Daley. He’d been mayor since 1955, a position he held until his death in 1976. His powerful status inside the party was a major reason why Chicago was chosen to host the convention. He saw it as an opportunity to showcase the Democrats’ achievements in the city.

When black civil rights leader Martin Luther King was assassinated in April that year, riots erupted in black communities in cities across the country, not least in Chicago’s West Side. Mayor Daley issued “shoot to kill” orders to his notoriously violent and racist police department to put down the unrest.

In response, SDS put out a leaflet titled “Wanted for incitement to murder, Richard J. Daley, Mayor of Chicago”. In a recent interview with International Socialist Review, Wayne Heimbach, an SDS activist at the time recalled: “We delivered this flyer all over Chicago’s West Side and it was an immediate success. There was even a TV report of a Chicago police officer trying to rip down one of the flyers we had put up.”1

In the months leading up to the convention, Daley sought to intimidate anti-war and anti-racist activists organising the demonstrations.

The initial position of SDS was not to come to Chicago, for fear of a bloodbath. Heimbach reports that this position had to change:

It was obvious that people were going to come anyway, so the national office asked me to write a short statement for New Left Notes making it clear what could happen in the city. I stated the official SDS position and said if people were going to come, be prepared to deal with the convention politically by having discussions with the many McCarthy supporters who were going to be here. I also suggested they bring a copy of their blood type with them, just in case.

The McCarthy organisation was asking people to come to Chicago to support their candidate. They were generally less experienced in the street actions that others had seen and they came to participate in what they thought would be a massive lobbying event. As the convention got underway, most of these different tendencies merged both in the streets and in how the city administration dealt with them. We all became comrades in the fight against the war.

The Chicago Police Department’s infamous “Red Squad” infiltrated any group organising for the convention, including even the National Lawyers Guild and the League of Women Voters. When one Red Squad member was caught breaking into the SDS offices, Mayor Daley openly defended them: “The police have a perfect right to spy on private citizens. How else are they going to detect possible trouble before it happens?”

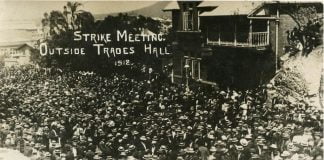

On the night before the convention protesters were confined to Lincoln Park, several kilometres from where the convention was being held. Although the park’s 11pm curfew was rarely enforced on hot summer nights, that night the police decided they’d clear it out at any cost. In opening the convention across town the following morning, Mayor Daley proclaimed: “As long as I am mayor of this city, there’s going to be law and order in Chicago.”

The largest confrontation between police and protesters took place on the Wednesday. Protest organisers had been granted a permit to protest close to the convention in Grant Park and some 10,000 turned out. However, the demonstration soon became angry when news that the peace plank proposed for the Democratic Party platform had been voted down. When one protester responded by lowering an American flag, police pushed through the crowd to arrest him. The National Guard began firing tear gas directly into people’s faces.

An attempt to march on the convention venue was blocked on the main street outside the Hilton Hotel, where most of the delegates were staying. Some 5000 protesters stood their ground against 800 National Guardsmen. In what became known as the “Battle of Michigan Avenue”, the authorities fired tear gas canisters, shoved protesters through restaurant windows, and knocked others to the ground, kicking them repeatedly. The media and even passers-by were also subject to police beatings.

The battle on Michigan was carried live to television audiences around the country, interspersed with a laughing Mayor Daley on the convention floor, making it seem he was celebrating the violence. When Connecticut senator Abraham Ribicoff took the podium to nominate George McGovern for president he declared: “With George McGovern we wouldn’t have Gestapo tactics on the streets of Chicago.” Daley’s face turned bright red as he shook his fist towards the stage and screamed, “Fuck you, you Jew son of a bitch, you lousy motherfucker, go home!”2

Eight protest leaders were subsequently tried for “inciting a riot” and the National Guard were again called out to contain protests outside the courtroom. Inside, Black Panther Party activist Bobby Seale called the judge a “fascist dog,” a “pig,” and a “racist”. The judge ordered Seale bound and gagged in the courtroom, and sentenced him to four years in prison for contempt.

The trial of the Chicago seven-which included Yippie leaders Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, and leading anti-war activists David Dellinger and Tom Hayden-was widely publicised and became a rallying point for further protest.

Eventually five of the defendants were fined $5000 and sentenced to five years jail. All of the convictions were later reversed by the US Court of Appeals.

The Democratic nomination

The growing opposition to the war had left Democratic president Lyndon Johnson’s administration badly damaged. His popularity plummeted in the weeks following the Tet Offensive.

In March 1968 Eugene McCarthy, challenging Johnson for the Democratic nomination on an anti-war platform, won 42 percent in the New Hampshire primaries and almost defeated Johnson. This shook the Democratic establishment, which frowned upon his anti-war stance. Four days later, Bobby Kennedy threw his hat into the ring, reversing his long held support for the Vietnam War and reinventing himself as an anti-war candidate. Two weeks after that, Johnson, increasingly unable to make a public appearance anywhere in the country without being confronted by thousands of anti-war demonstrators, announced he was pulling out of the race.

McCarthy’s campaign held its own for a while, with primaries victories in states such as Wisconsin, Oregon, and Pennsylvania. However, he was eventually overtaken by Kennedy in the California primary on June 5…the very night Kennedy was assassinated.

From then until the Chicago convention, the Johnson administration and congressional and state Democratic Party leaders swung their support squarely behind Johnson’s pro-war Vice President, Hubert Humphrey. The US ruling class had increasing concerns that the growing anti-war movement was becoming a power that could challenge their interests-concerns which help to explain why the protests at the Chicago convention were repressed so viciously.

The Democratic Party machine, not least Mayor Daley, made sure that the convention installed Hubert Humphrey as its presidential candidate, even though he hadn’t won a single primary among the Democratic Party rank-and-file. Humphrey went on to lose to Richard Nixon in November, not least because of disillusionment among its supporters.

The Chicago convention had again seen the Democratic Party reveal its true colours-as a thoroughly ruling class party which would never accept a presidential candidate unwilling to serve the interests of corporations and the rich in the US. The party which during the US Civil War of the 1860s was backed by the Southern slave owners; the party which before and during WWII mobilised troops to break strikes, and which after the war under Truman failed to repeal the Taft-Hartley anti-union bill; the party which in the 1990s under Bill Clinton would cripple Iraq with sanctions, bomb both Belgrade and a pharmaceutical factory in Sudan, and on the home front “end welfare as we know it”.

In 1968, the same Democratic Party machine was dead against allowing even a moderate anti-war candidate like Eugene McCarthy stand as its presidential candidate in order to reflect the growing tide of opposition to the Vietnam War.

If we fast forward to 2008, the experience of the Chicago convention should make us pause before concluding from Obama’s radical rhetoric that he is an anti-establishment candidate. On the contrary, his comfortable relationship with corporate and militarist America has made him a sufficiently acceptable nominee for significant sections of the elite who are the true rulers of US society. As if to underline this fact, since securing the presidential nomination, Obama has dropped his call for a wholesale withdrawal from Iraq, and says he will expand the US’s military presence in Afghanistan.

The legacy of Chicago 68

The protests at the Chicago convention were a major turning point for the US left. The left was battered both inside and outside the convention. But the experience taught thousands of activists about the nature of the Democratic Party and why it would never take up the movement’s demands, as well as about the ruthless violence the US ruling class was prepared to use to break the movement when it became a threat to its ability to continue the war. For many of the 1968 generation, “where were you during the convention?” remains a defining question.

Many McCarthy supporters left Chicago having reached revolutionary conclusions, rejecting the notion that the Democratic Party represents “lesser evilism”. This strengthened the ranks of those who had already lost their illusions in the Democrats as a result of Lyndon Johnson’s military escalation in Vietnam. As Lance Selfa puts it in The Democrats and the politics of lesser evilism, “Many of the same people who raised the campaign chant, ‘Half the way with LBJ,’ [in 1964] later marched chanting, ‘Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids have you killed today?'”

The Chicago experience, on top of the assassination of Martin Luther King, accelerated the formation of the openly revolutionary Black Panther Party.

Political debates inside SDS sharpened. As two San Francisco socialists, Jack Weinberg and Jack Gerson wrote in 1969: “What began as a movement in many ways resembling a super-idealistic children’s crusade to save the world was becoming increasingly grim and increasingly serious. The stakes had been raised. This forced the radical movement to take itself-and as a result of its ideas-more seriously”.

The experience of Chicago showed the need for an understanding of the structures of society-especially the state power held by the ruling class which it was using to wage war in Vietnam and brutally beat demonstrators at home. In the face of this threat to the anti-war movement’s continued existence activists needed to understand how the state could be beaten if they were going to change society.

Some drew the conclusion that they should prepare for military-style confrontations with police. This approach was typified in the disastrous Days of Rage organised by the Weathermen, when they raced through the streets armed with pipes attacking police, windows, and cars.

Fortunately others realised the importance of reaching out to win wider support for the movement, and trying to win over the majority of ordinary working class people. The following year in 1969 two million people across the US took part in the first Moratorium against the Vietnam War. While it took until 1975 for the US to finally make its humiliating withdrawal from Vietnam, the seeds for this defeat were sown in 1968 by both determined resistance of the Vietnamese and the coming of age of the anti-war movement.

Conclusion

At the height of this year’s primaries, it was feared that this year’s Democratic Convention would be a re-run of 1968, where the Clintons would lean on the super-delegates to steal the nomination from a more popular candidate.

But the flipside of the enthusiasm for Obama’s candidature has been the disappearance of mass demonstrations against the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as many have been pulled behind his campaign. This has not been helped by the fact that the main anti-war coalition, United For Peace and Justice, has tended to emphasise phoning Congress, voter registration and lobbying.3

Nevertheless, protests are being planned by a coalition including Iraq Veterans Against the War, CODEPINK, United for Peace and Justice, Veterans for Peace, the Colorado Green Party, Students for a Democratic Society, Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center, the International Socialist Organization, Progressive Democrats of America, Jobs with Justice, and others.

Immigrant rights organisations are also mobilising outside the Democratic convention to demand legalisation for the country’s millions of undocumented migrant workers. The anti-war movement is also planning to mobilise outside the Republican convention in Minneapolis on September 1.

When Obama accepts his party’s nomination in rock star style at the 75,000 capacity home of the Denver Broncos, there will also be a growing disquiet that he has started to embody the characteristics of the very kind of a status quo politician that he lampooned during the primaries race.

The Democrats’ anti-war credentials have already been tested and been found wanting. Since being swept into power in Congress in 2006, they have continued to approve hundreds of billions of dollars in funding for the war. But with mass public opinion still strongly against the war, a mass action strategy that seeks to involve workers, soldiers and students in solidarity with the resistance of occupied peoples remains the only viable way to bring an end to the wars-and to ensure that US imperialism suffers something akin to the humiliation in Vietnam, so that future US military intervention becomes impossible.

Notes

1. “A look back at the 1968 Democratic Convention”, International Socialist Review, July-August 2008.

2. Cited in Art Shay, “The Democratic Convention-Chicago 1968”, www.swans.com/library/art14/ashay01.html

3. See Ashley Smith, “Which way forward for the antiwar movement?”, International Socialist Review, July-August 2008.