Karl Marx’s most important insight was the potential role of the working class to overturn capitalism and build a new kind of society, writes David Glanz

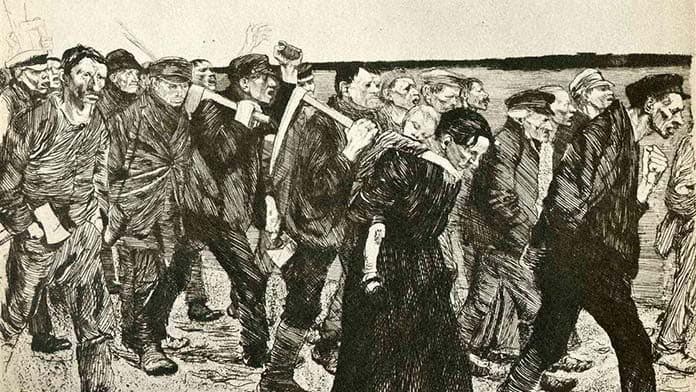

On 4 June 1844, weavers marching for higher wages broke into the headquarters of the Zwanziger Brothers, a textile company in Silesia, and destroyed everything.

The next day, 5000 weavers and their families smashed machines and ransacked homes and offices.

Industrialists called in the Prussian military, who fired on the crowd, killing 35.

German radicals were appalled by the brutality, but most either saw the workers as helpless victims or criticised them for fighting for higher wages rather than for democratic reform.

The young Karl Marx (he had just turned 26) drew starkly different conclusions. First, he insisted that radicals should learn from the workers, not lecture them.

“Confronted with the initial outbreak of the Silesian revolt no man who thinks or loves the truth could regard the duty to play schoolmaster to the event as his primary task. On the contrary, his duty would rather be to study it to discover its specific character.”

Second, he declared that in fighting over wages and therefore the terms of their exploitation, “the proletariat proclaims its opposition to the society of private property”.

In other words, they were paving a path towards social and economic liberation, rather than just a parliamentary system that would leave economic privilege intact.

And third, he argued that as a consequence feudal Germany should see that “… only in the proletariat can it discover the active agent of its emancipation”.

The working class, although small and still unorganised, offered leadership to all those sick of the old society.

Four years later, writing the Communist Manifesto with his collaborator Frederick Engels, he brought his themes together more clearly.

“All previous historical movements were movements of minorities, or in the interest of minorities. The proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority, in the interest of the immense majority.

“The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole superincumbent strata of official society being sprung into the air.”

It was a remarkable insight. At that point capitalism held sway over only a tiny proportion of the world: Britain, zones in northern Europe and pockets of the north-eastern US.

Yet Marx was arguing that the emerging working class which capitalism was still in the process of creating had the agency—the power, the motivation and the potential—to overthrow the new system and take power, thereby liberating all humanity.

It was his most revolutionary idea.

Other classes of direct producers had fought back—slave revolts and peasant uprisings had shaken the wealthy many times over millennia. But while the poor could destroy the possessions and even the lives of their masters, they lacked the basis for forming a new, equal society.

The new working class, however, was not only central to production and therefore to the generation of profits, but was brought together in the workplace as a collective.

Workers cannot split a factory or workplace between them individually as peasants can divide the lord’s land. And workers have no subordinate class to oppress in turn. That’s why, Marx argued, it is the class with radical chains.

Capitalism and crisis

Marx was not merely a critic of capitalism, however. He was the first to grasp why crisis was endemic to the system.

Capitalism, he argued, was a system of many competing capitals. Each capitalist attempted to grab a larger share of the surplus being created. To do so, they would install the newest, most efficient machinery, thereby reducing the cost of each item being produced. New technologies introduced into British cotton factories during the industrial revolution, for instance, like the steam engine and the power loom, allowed cotton to be manufactured at a cheaper and cheaper cost.

But in doing so, they were reducing the proportion of workers in the system—either by cutting jobs or by making the same number of workers produce more.

In the short term, profits for the innovators would go up. But workers are the only source of surplus under capitalism—the only element of the system that generates more than it takes to reproduce itself.

By increasing the proportion of machinery (what Marx called “dead labour”) to living labour, the overall rate of profitability falls, capitalists stop investing and the system goes into crisis.

Marx saw the crises of capitalism and working class resistance as two sides of the same coin.

But others then and now disagree. Marx’s contemporary, the anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, was dismissive of the idea that workers could take the fightback into their own hands, saying:

“There are about forty million Germans. Are all forty million going to be members of the government?”

He advocated revolution, but insisted the leadership would not come from workers themselves but from an exclusive and shadowy organisation, “the secret universal association of international brothers”.

Journalist Daniel Ben-Ami, writing on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis, also dismissed the working class’s potential to challenge for power.

“A lot has changed in the nearly 160 years since the Manifesto was written. For a start hardly anyone seriously believes that the spectre of communism is on the horizon. Even those sympathetic to the working class tend not to see it as a force that is likely to transform society in the short or medium term.”

Part of the problem is the confusion over what is meant by working class. A recent report from the Australian National University, Class, Capital and Identity in Australian Society, argues that there are six classes.

Social capital (prestige) and cultural capital (how you spend your free time) are seen important dividing lines, along with education and spending habits.

The report asks: “If you have the night off or away from the kids, what do you do? Do you go to see a movie? Or do you go and see the theatre or do you sit at home and play on Facebook?”

But for Marx, class was defined by people’s relationship to capital. So a bus driver who goes to the Opera House and a driver who stays home and watches Netflix both have to get up early and report to the depot. Both need to join a union and fight back if they are going to improve their wages and conditions.

Another source of confusion is that many assume Marx was writing purely about a working class made up of blue-collar, manufacturing workers and that the rise of service industries makes Marx’s views redundant.

This is wrong on a number of levels. During Marx’s time, a significant section of the working class was made up of mostly female domestic servants.

Today, the service sector not only includes office workers, shop staff and teachers but truck drivers, postal workers and council workers—all just as likely to join a union and strike as factory workers.

Understood that way, the working class is growing, not declining.

In the US alone, the working class grew between 1990 and 2008 by 27.3 million. Between 1980 and 2012, the global workforce grew from 1.2 to 3 billion.

Workers’ potential

Critics also doubt the potential of the working class to challenge the system. In January 1968, the radical intellectual André Gorz wrote:

“In the foreseeable future, there will be no crisis of European capitalism so dramatic as to drive the mass of workers to revolutionary general strikes.”

Four months later, ten million French workers were on strike, many occupying their workplaces, in a struggle with revolutionary implications.

Such struggles do not exist just in liberal democracies. In many countries in the 1930s and 1940s, working class organisation of any kind was completely wiped out.

Yet again and again, massive struggles burst to the surface after the Second World War.

In Japan, despite being under US occupation, workers went on mass strike, taking over workplaces from the Yomiuri newspaper to coal mines and organising production themselves.

In Italy, where the fascists had been in power since 1922, workers at the Fiat factories struck in 1943. In Germany, where unions were banned in 1933, hundreds of thousands of workers were on strike in the Ruhr in 1947 and 1948.

France saw insurrectionary strikes by workers at Renault in Paris in 1947 and a mass strike by coal miners in 1948.

The strike wave arrived later in the Eastern Bloc, starting with the uprising of East German workers in 1953, Poznan in Poland 1956, Hungary 1956, Novercherkassk in Russia in 1962 and Czechoslovakia in 1968. Stalinist dictatorship could not stop workers fighting back, either.

The same lived experience that led the Silesian workers to act was being felt more than a century later, and can be seen again today in the teachers’ strikes in the US or the 120,000 who took to the streets of Melbourne earlier this year.

For Marx, workers are not victims. They are the collective class who generate the wealth in society and who, when they move as one, can throw the whole rotten structure of capitalism into the air.