David Glanz tells the story of the slave revolution in Haiti that defeated the combined might of European imperialism to win its freedom

Asked to name a slave revolt, some people will know of the uprising against the Roman empire led by the gladiator Spartacus from 73-71 BCE—a fight for freedom that ended in suppression and death but whose inspiration has echoed down the centuries. Far fewer know of the slave revolt that won.

Some 150 years before the successful anti-colonial struggles of the mid-20th century, African slaves defeated the forces of the French, Spanish and British empires to establish an independent black republic—declared on 31 December 1803 and named Haiti.

Those who ran and profited enormously from the trans-Atlantic slave trade helped create the central ideological building block of modern racism—the idea that those in black skin were profoundly and naturally inferior, indeed less than human.

Yet the revolt that liberated Haiti was made possible by the organisation and intelligence of a slave population, two-thirds of whom had made the “middle passage” from Africa to the Caribbean—traumatised by kidnapping and enslavement, but born in freedom and determined to reclaim it.

The slavery against which they rose up was a crucial enabler for the rise of capitalism. As Karl Marx put it: “The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”

The rising French bourgeoisie, who were making super-profits from the trade in humans, therefore had no interest in ending slavery, whatever their talk of liberty and equality.

Instead the slave revolt was to find its allies not among the enlightened upper classes but among the poor French masses. But most of all, it relied upon the courage and determination of the slaves themselves.

Haiti is the western half of a mountainous island claimed for the Spanish king by Christopher Columbus in 1492 and named Santo Domingo.

Columbus brought Christian civilisation, which through slavery, rape and murder reduced the indigenous population of up to one million to 60,000 in 15 years.

In 1517, the Spanish imported 15,000 African slaves to work the lucrative sugar plantations.

Greedy for a share of the spoils, the French seized the western part of the island and their ownership was confirmed by treaty in 1695.

The eastern side remained under Spanish rule. Today it is the Dominican Republic.

The French tried to use whites on the new sugar and coffee plantations but they couldn’t cope with the conditions, so the slave trade boomed. In 1666 alone, 108 ships from the French port of Nantes took 37,430 slaves to Santo Domingo, returning 15-20 per cent on the merchants’ capital.

The slave trade, and the profits from the plantations that the slaves worked, generated enormous wealth for the rising French bourgeoisie. Echoing Marx, the Caribbean Trotskyist CLR James wrote, “Nearly all the industries which developed in France during the 18th century had their origin in goods or commodities” for Guinea in West Africa or America.

“The capital from the slave trade fertilised them; though the bourgeoisie traded in other things than slaves, upon the success or failure of the traffic everything else depended.”

As revolution broke out in 1789, French exports from its colonies were worth 17 million pounds, of which 11 million came from the trade with Santo Domingo.

To generate this wealth and to maintain control, French “civilisation” used the most bestial methods. Slaves were whipped and salt rubbed into the wounds. Many were mutilated, including their sexual organs.

CLR James, the main English-language historian of the slave revolt, wrote: “Their masters poured burning wax… boiling cane sugar over their heads, burned them alive, roasted them on slow fires, filled them with gunpowder and blew them up with a match, buried them up to their neck and smeared their heads with sugar…”

When the revolt came, it was a brutal affair. But the slaves’ violence was still just a pale shadow of the routine way in which the slave-owners managed their business.

The first resistance came from the Maroons—slaves who had escaped to create free communities in the mountains.

Then, in 1789, revolution broke out in France and everything changed. The bourgeoisie challenged the feudal monarch under the slogan of “Liberty, equality, fraternity”, signifying a fight for the freedom to make profits.

But with the slave trade such a profitable exercise, the slogan was still-born on arrival in Santo Domingo.

The white slave-owners and merchants refused political freedom even for the mulattos, those descended from white fathers and black mothers. They were free and allowed to own property but their skin colour meant they would always be marginalised.

In 1790, the mulattos, led by Vincent Oge, rose up and were smashed. A year later, 100,000 slaves rose up in a struggle that proved much more successful.

On 29 August 1793, the French colonial ruler freed the slaves in the north province (with severe limits on their freedom). In September and October, emancipation was extended throughout the colony.

On 4 February 1794, the French National Convention, under the leadership of Maximilien de Robespierre, abolished slavery in France and all its colonies, in the teeth of opposition from the French merchants.

It was the highpoint of the revolution as the radicalism of the urban poor marginalised the bourgeoisie, winning a decisive victory against both the feudal aristocracy and the slave trade, known as the “aristocracy of the skin”.

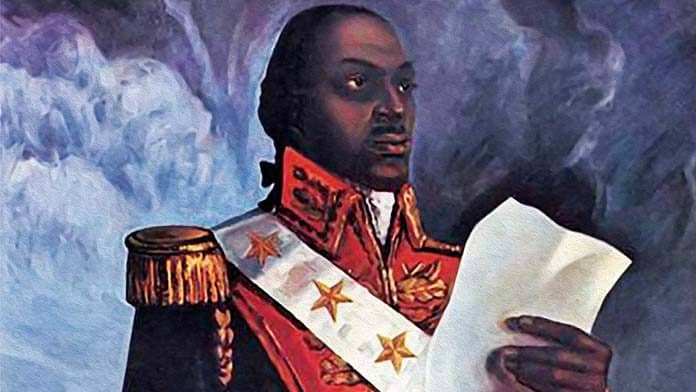

Toussaint L’Ouverture

The struggle, however, was far from over. Under the leadership of an educated slave, Toussaint L’Ouverture, the slave armies fought the Spanish, who had taken advantage of the chaos to attempt to retake the west of the island.

The slave army then had to confront the might of the British, who were enthusiastic to add the profits of the sugar plantations to an empire that had recently lost its American colonies.

L’Ouverture’s men fought courageously, at one point winning seven battles in seven days, and the British were driven out in 1798 with the loss of 80,000 soldiers.

The peace was brief. In 1802, Napoleon, having restored slavery in the French colony of Guadeloupe, sent an invading army.

His forces massacred or drowned thousands. The French imported 1500 dogs and taught them to rip blacks apart alive, while whites dressed up and watched the spectacle.

L’Ouverture, who died in 1803, had one major advantage in building his army of ex-slaves—whichever colonial power controlled Santo Domingo, they knew slavery would be restored. Only victory would bring freedom. And the ex-slaves fought with all their power.

When, in 1793, royalist French colonists tried to overthrow French Revolutionary rule: “10,000 blacks swooped down from the hills on to the city. The road from the heights ran along the sea-shore, and the sailors who remained on the ships in the harbour could see them hour after hour swarming down …

“Ten thousand refugees crowded on to the vessels in the harbour and set out for the United States … it was the end of white domination in San Domingo.”

Against Bonaparte’s men, the ex-slaves burned the country to starve the invaders. Fighting both as guerrillas and conventional soldiers, they took death in their stride.

When a black chief hesitated at the sight of the scaffold, CLR James writes: “His wife shamed him. ‘You do not know how sweet it is to die for liberty!’ And refusing to allow herself to be hanged by the executioner, she took the rope and hanged herself.”

They won a mighty victory. As CLR James put it: “The slaves defeated in turn the local whites and the soldiers of the French monarchy, a Spanish invasion, a British expedition of some 60,000 men, and a French expedition of similar size under Bonaparte’s brother-in-law…

“The transformation of slaves, trembling in hundreds before a single white man, into a people able to organize themselves and defeat the most powerful European nations of their day, is one of the great epics of revolutionary struggle and achievement.”

Yet, with the rise of counter-revolution in Bonapartist France, it could not be a total victory. France refused to recognise the newly independent country’s sovereignty until 1825, and only then in exchange for 150 million gold francs.

This fee, demanded as retribution for the “lost property—slaves, land, equipment, etc—of the former colonialists, was later reduced to 90 million.

Haiti agreed to pay the price to lift a crippling embargo imposed by France, Britain and the United States—but to do so, had to take out high interest loans. The debt was not repaid in full until 1947.

The 12-year war of liberation by the slaves was fundamentally a class struggle, not a race war. Its fate was tied to the rise and fall of the French Revolution. The greatest freedoms were won when the oppressed on both sides of the Atlantic made common cause.

But most of all the war, and victory, was driven by the commitment and enormous self-sacrifice of former slaves—the one class that could not make peace with French capitalism.