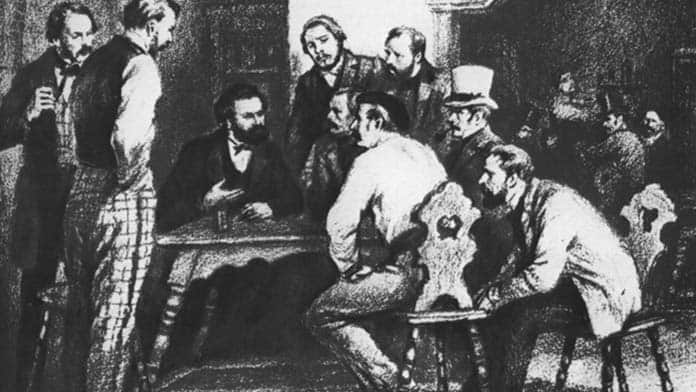

Lachlan Marshall examines Karl Marx’s 1844 Manuscripts, where he analysed the alienation of working class life in the developing factory system

The Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts were Karl Marx’s first serious work on political economy and the capitalist system.

Written in 1844, they were published in German only in 1932 and English in 1959.

The Manuscripts were completed before his full political framework had been developed.

But they contained for the first time his analysis of the emerging struggle between the new class of waged workers and the capitalists who employed them.

A key concept that Marx examines in the Manuscripts is alienation. Marx takes the concept of alienation from the German philosopher Hegel. For Hegel, alienation was simply the result of understanding the world in the wrong way. His solution to this was intellectual and religious enlightenment.

But Marx saw productive labour in the real world as what was most fundamental to human life.

As he pointed out, the survival of any human society relies before anything else on its capacity to meet people’s basic needs like food and shelter.

What distinguishes humans from other animals is our ability to consciously and collectively produce what we need to survive. This capacity for labour is what makes us human.

Marx applied Hegel’s concept of alienation, or estrangement, to the way capitalism distorts this labour process and therefore “the essence” of what makes us human. His concept of alienation was therefore fundamentally materialist, concerned not simply with ideas but processes in the real, material world.

Marx outlines four ways that workers are alienated under capitalism.

The first is that we lose control of the products of our labour because they belong to the boss, not to us.

“The worker cannot use the things he produces to keep alive or to engage in further productive activity… The worker’s needs, no matter how desperate, do not give him a licence to lay hands on what these same hands have produced, for all his products are the property of another.”

The second is alienation from the process of labour itself. The lack of control over the workplace and how it is run creates a sense of powerlessness among workers.

As a result, Marx writes: “Labour is exterior to the worker… Therefore he [the worker] does not confirm himself in his work, but denies himself, feels miserable instead of happy, deploys no free physical and intellectual energy, but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.”

The extent of psychological distress under capitalism is one symptom of this kind of alienation.

Flowing from this is alienation from other people. Under capitalism we’re forced to compete with other workers for access to the products of our labour, employment, housing and other necessities.

“An immediate consequence of man’s alienation from the product of his work, his vital activity and his species-being, is the alienation of man from man.”

Finally, we are alienated from our human nature, or “species-being” as Marx calls it. This includes alienation from the natural world, of which humans are part.

“In estranging from man (1) nature, and (2) himself, his own active functions, his life activity, estranged labour estranges the species from man. It changes for him the life of the species into a means of individual life.”

Crisis and revolution

Marx links this philosophical discussion of alienated labour, the way workers have lost control in the production process, to economic crisis. Without production being under the conscious, democratic control of workers, market competition leads to crises.

“Produce with consciousness as human beings—not as dispersed atoms without consciousness of your species—and you are beyond all these artificial and untenable antitheses. But as long as you continue to produce in the present unconscious, thoughtless manner, at the mercy of chance—for just as long trade crises will remain.”

In the Manuscripts Marx foreshadows many of the ideas he expands upon in later works. He describes capitalism as a system based on the conflict between capital and labour, and explains how this antagonism is inevitable, not just “an accidental event” as other political economists see it.

For Marx, class conflict is built into the system, and not just for workers: “The rent of land is established through the struggle between tenant and landlord. Throughout political economy we find the hostile contraposition of interests, struggle, warfare, recognised as the basis of social organisation.”

Marx describes how capitalism changes class relations in the countryside, which leads to growing polarisation between workers and capitalists: “The final result is therefore the disappearance of the difference between capitalist and landowner, so that thus there remain, on the whole, only two classes in the population, the working class and the class of capitalists.”

Marx concludes that this process “necessarily leads to revolution”.

This analysis of the working class introduced something new to the socialist movement: that the working class is not just a class that suffers but is a revolutionary class.

If private property in the hands of the capitalist class is the result of the products of labour being alienated from the working class, then the abolition of private property through revolution is the way to end alienation.

And because the subjugation of the working class is the basis for all other forms of oppression, the emancipation of the working class is the precondition for universal emancipation.

“From the relationship of estranged labour to private property it follows, further, that the emancipation of society from private property, etc., from servitude, is expressed in the political form of the emancipation of the workers—not as though it is only a question of their emancipation but because in their emancipation universal human emancipation is comprehended; and this is so because the whole of human servitude is involved in the relationship of the worker to production, and all relations of servitude are only modifications and consequences of this relationship.”

Marx wrote the Manuscripts before he came to a full appreciation of the revolutionary potential of the working class.

That came shortly afterwards and was confirmed in his experience of the 1848 revolutions and the Paris Commune in 1871, which showed that workers could build a socialist society based on workers’ power.

But the Manuscripts offer an insight into the early development of Marx’s revolutionary ideas.