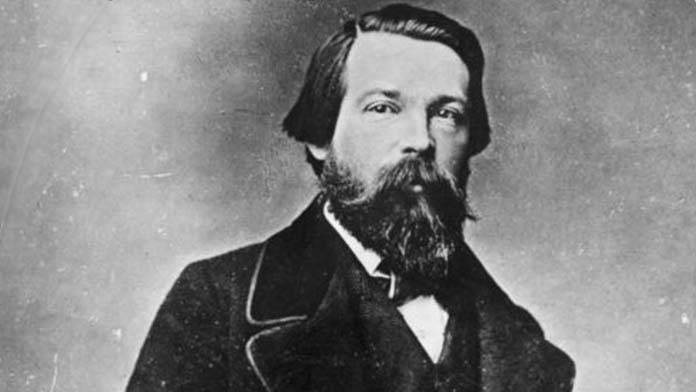

Adam Adelpour looks at the important contribution Engels made to the development of Marxist ideas, 200 years on from his birth

Friedrich Engels was Karl Marx’s collaborator and co-author of the Communist Manifesto, the founding publication of the world communist movement.

He dedicated his life to the aim of workers’ revolution and developed ideas that helped lay the foundation of the Marxist tradition.

Engels began life in 1820 as a child of privilege in the provincial manufacturing town of Barmen in modern day Germany. His family owned manufacturing interests, and he grew up in an environment of religious piety and conservatism under the rule of the Hohenzollern Monarchy.

However, Barmen was not immune to the world shaking events across Europe. The industrial revolution, the development of capitalism and the impact of the French Revolution a few decades before were the foundations of the social and political order.

His exposure to radical political ideas began at school, but solidified when he did his military service in Berlin. He attended university lectures and was initially drawn to the ideas of the German philosopher Hegel.

A group called the Young Hegelians saw in Hegel’s ideas a promise of change and an end to the stifling, conservative and repressive political, social and cultural conditions that they lived under. At their most extreme left their politics were atheist, liberal and republican.

Engels’ Hegelian phase was a long way from his future of barricade fighting, political exile and incitement of proletarian revolution.

The left Young Hegelians wrote cultural criticism which contained veiled barbs directed at the Monarchy and religious dogma.

Despite Young Hegelian rebellion being largely restricted to the realm of ideas and culture, Engels’ ideas were soon to be profoundly impacted by far more earthly forces.

The Working Class in England

After moving to England for work in the family business, Engels came into direct contact with the powerful working class Chartist movement.

Shortly before he arrived, Britain had been thrown into turmoil by the Plug Plot riots in 1842. Almost half a million were involved in a general strike, shutting down factories, sabotaging machinery and clashing with police. The eruption was driven by the demand for the vote to remedy dire living and working conditions.

It was in this cauldron of working class rebellion that Engels began to develop many of the key ideas of historical materialism or Marxism, completely independent of Marx himself. Some of these were crystallised in his short book The Condition of the Working Class in England, published in 1845.

The book describes the abject living conditions of the modern working class in England. Much of its grimy accuracy was a result of the guidance of Engels’ working class partner Mary who was able to shepherd him into the heart of Manchester’s slums.

But the book explains that these conditions were not simply a moral failing, but a product of the dynamics of capitalism.

The revolutionary component of Engels’ argument was that workers could be the agents of change rather than mere victims. He said that because, “the proletariat was called into existence by the introduction of machinery”, capitalism was creating the force that would deliver its destruction. He prophetically argued that England in the 1840s was a glimpse into the future of class conflict in Germany and elsewhere as capitalism spread.

Engels described himself as “second fiddle” to Karl Marx, and is often relegated to a place in Marx’s shadow. But this doesn’t do justice to his contribution.

The lifelong relationship between Marx and Engels only made its start because both men were arriving at the same political conclusions independently.

Prior to the publication of the The Condition of the Working Class, Marx—who had also frequented Young Hegelian circles—viewed Engels with a degree of contempt. Marx was breaking away from Young Hegelian ideas, and he mistakenly saw Engels as a political apologist for an obsolete set of ideas.

However, Marx warmed to Engels quickly once it became clear that had arrived at the same conclusions about the working class and revolution, saying he, “Arrived by another road…to the same result as I.”

In fact Engels was in advance of Marx in some respects. His direct experience of the workers’ movement in England meant he was the first to grasp the importance of trade unions, and he recognised the importance of political economy even before Marx.

In 1847 they would co-author The Communist Manifesto, boldly laying out their common strategy for change and its theoretical foundations in an accessible form. It was Engels, not Marx, who penned many of substantial elements of the Manifesto.

Engels and Marx sharply differed from other socialists of the time, who they described as “utopian socialists”. The likes of Charles Fourier in France and Robert Owen in England recognised the grave ills of capitalism, and concocted elaborate visions of a better world. But their strategy consisted largely of proselytising their ideas to the powerful who they expected to hand down change from above.

In contrast, Engels and Marx agreed that the battering ram that can deliver social change was to be found in the flesh and blood of the revolutionary working class.

A spectre is haunting Europe

The Communist Manifesto begins with the famous words “A spectre is haunting Europe”. In 1848—immediately after its publication—a wave of revolutions against the Monarchic regimes of Europe broke out. Initially the revolutions were demanding liberal republican government, along the lines of the earlier French Revolution. Marx and Engels threw themselves into the fray.

Engels returned to Germany to join the revolt against the Monarchy on the barricades around Barmen, then, as the revolution collapsed, he joined its last stand south of Frankfurt.

But it was events in France—ruled again by a reactionary Monarchy—that confirmed the predictions of the Manifesto most clearly.

Here for the first time the organised working class emerged as an armed wing of the revolution with its own demands and organisation, distinct from those from the middle classes. In addition to liberal demands for freedom of the press and other political rights, workers demanded jobs and employment in vast state workshops.

After the abdication of the King workers came into violent conflict with the liberals who disgraced themselves by deploying the National Guard to crush the workers’ uprising.

The 1848 revolutions were ultimately smashed by a victorious wave of reaction. Revolutionaries were driven into exile.

Marx and Engels fled back to England. Opportunities for practical activity dried up and Marx and Engels were reduced to the status of impoverished political refugees.

Despite this, the following two decades saw Marx produce Capital, his treatise on the nature of capitalism, its dynamics and its tendency to sow the seeds of its own destruction through crisis, false scarcity and the creation of a powerful working class.

Engels’ role in the production of Capital was two-fold. He played the role of Marx’s editor and primary theoretical sounding board, but he also abandoned many of his own theoretical and political ambitions to resume work in his family’s business in order to financially support Marx’s work.

The First International

From the late 1860s there was a revival in class struggle and Marx and Engels returned to the battleground of practical politics. In 1864 Marx helped found the International Working Men’s Association under the banner of the slogan “Workers of the World Unite”.

They published Capital shortly after. Engels went on a political offensive to spread the ideas of Marx within the socialist movement in Europe and America.

The establishment of the First International followed the working class support for the boycott of Southern cotton in England during the US Civil War, in opposition to slavery. This was despite the boycott’s devastating effect on English manufacturing areas and on workers’ jobs.

In Europe the First international was also reviled by the ruling classes for its strident support for the 1871 Paris Commune, where workers briefly seized political power in the capital city of a major power for the first time in history.

Engels was able to dedicate himself full time to the revolutionary cause, following his retirement from the family business in 1869.

In this period he consolidated the Marxist theoretical tradition by summing up its tenets in a book titled Anti-Duhring, an attack on the ideas of Dr Eugen Duhring, who was gaining popularity among German socialists. The book helped popularise Marxist theory, and was the first Marxist text read by the revolutionaries in Russia who would go on to found the Bolshevik party.

After Marx died, Engels also produced his ground-breaking analysis of women’s oppression The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. While some of the underlying anthropology has been discredited, the book’s central theoretical argument that women’s oppression is not innate to human biology or society endures as a key weapon in the battle against sexism. His other writings on the environment in The Dialectics of Nature highlight the reciprocity between human society and the environment in a way that pre-figures what is now known as ecology.

Engels spent his last years helping guide the growing international socialist movement that he and Marx had helped shape. By the time of Engels’ death in 1895, there were mass socialist parties dedicated to Marxist principles across Europe, most importantly the German Social Democratic party with millions of followers. Just over 20 years later the workers of Russia would seize power, inspired by many of his writings.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, billionaires’ wealth has increased 27.5 per cent to $14 trillion. Engels predicted a time where, “The war of the poor against the rich, now carried on in detail and indirectly, will become direct and universal.” Two hundred years after his birth—amid pandemic, economic crisis and looming climate catastrophe—Engels’ lifelong commitment to workers’ revolution should serve as an inspiration to all who demand a better world.